Economy of Scotland in the Middle Ages

There are also Scottish coins, although English coinage probably remained more significant in trade, and until the end of the period barter was probably the most common form of exchange.

Craft and industry remained relatively undeveloped before the end of the Middle Ages and, although there were extensive trading networks based in Scotland, while the Scots exported largely raw materials, they imported increasing quantities of luxury goods, resulting in a bullion shortage and perhaps helping to create a financial crisis in the fifteenth century.

[2] Its north Atlantic position means that it has very heavy rainfall, which encouraged the spread of blanket peat bog, the acidity of which, combined with high level of wind and salt spray, made most of the western islands treeless.

[7] However, Gilbert Markus highlights the fact that most of these figures were not church-founders, but were usually active in areas where Christianity had already become established, probably through gradual diffusion that is almost invisible in the historical record.

[10] Although there is no reliable documentation on the impact of the plague, if the pattern followed that in England, then the population may have fallen to as low as half a million by the end of the fifteenth century.

Lacking the urban centres created under the Romans in the rest of Britain, the economy of Scotland in the early Middle Ages was overwhelmingly agricultural.

With a lack of significant transport links and wider markets, most farms had to produce a self-sufficient diet of meat, dairy products and cereals, supplemented by hunter-gathering.

[17] The early Middle Ages were a period of climatic deterioration, with a drop in temperature and an increase in rainfall, resulting in more land becoming unproductive.

In the period c. 1150 to 1300, warm dry summers and less severe winters allowed cultivation at much greater heights above sea level and made land more productive.

[25] In the late Middle Ages, average temperatures began to reduce again, with cooler and wetter conditions limiting the extent of arable agriculture, particularly in the Highlands.

[26] The rural economy appears to have boomed in the thirteenth century and was still buoyant in the immediate aftermath of the Black Death, which reached Scotland in 1349, and may have carried off a third of the population.

However, by the 1360s there was a severe falling off in incomes that can be seen in clerical benefices, of between a third and half compared with the beginning of the era, to be followed by a slow recovery in the fifteenth century.

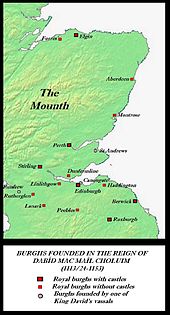

[14] Most of the early burghs were on the east coast, and among them were the largest and wealthiest, including Aberdeen, Berwick, Perth and Edinburgh, whose growth was facilitated by trade with the European continent.

In the south-west, Glasgow, Ayr and Kirkcudbright were aided by the less-profitable sea trade with Ireland, and to a lesser extent France and Spain.

These included the manufacture of shoes, clothes, dishes, pots, joinery, bread and ale, which would normally be sold to inhabitants and visitors on market days.

By the late fifteenth century, there were the beginnings of a native iron-casting industry, which led to the production of cannon and of the silver and goldsmithing for which the country would later be known.

For most of the period there are not the detailed custom accounts that exist for England, that can provide an understanding of foreign trade, with the first records for Scotland dating to the 1320s.

[33] In the early Middle Ages, the rise of Christianity meant that wine and precious metals were imported for use in religious rites, and there are occasional references of trips to and from foreign countries, such as the incident recorded by Adomnán in which St Columba went to a port to await ships bearing news, and presumably other items, from Italy.

The disruption of the Wars of Independence, which not only limited trade but damaged much of the valuable agricultural land of the Borders and Lowlands, meant that this fell in the period 1341–42 to 1342–43 to 2,450 sacks of wool and 17,900 hides.

[27] In the late Middle Ages, the growing desire among the court, lords, upper clergy and wealthier merchants for luxury goods, that largely had to be imported (including fine cloth from Flanders and Italy),[14] led to a chronic shortage of bullion.