Economic history of the Netherlands (1500–1815)

The financial strength proved more durable, enabling the Netherlands to play the role of a major power in the European conflicts around the turn of the 18th century by hiring mercenary armies and subsidizing its allies.

The regents of the Republic more or less abandoned its Great-Power pretensions after 1713, cutting down on its military preparedness in a vain attempt to pay down this overhang of public debt.

Wars with Great Britain and France at the end of the 18th century, and attendant political upheavals, caused a financial and economic crisis from which the economy was unable to recover.

The newly independent Kingdom of the Netherlands was faced in 1815 with an economy that was largely deindustrialized and deurbanized, but still saddled with a crippling public debt, which it was forced to repudiate (the first time that the Dutch state defaulted since the dark pre-independence days of the Revolt).

The territory of the northern maritime provinces that would later constitute the Dutch Republic (previously disparate fiefs of the Holy Roman Empire) were gathered together under the suzerainty of the Duchy of Burgundy in the late 15th century.

[1] In the late Middle Ages these territories already formed part of a premodern economic system with its own measure of integration, brought about by intensive trade relations.

Flanders and the Duchy of Brabant were further advanced industrially than Holland and Zeeland, and the metropolitan port city of Antwerp held the position of main entrepôt in northwestern Europe, as the hub in a far-flung trade web that spanned the whole known world.

The ports in the northern provinces had only a regional importance, though Amsterdam had already built up a preponderant position in the Baltic trade, after making inroads on the monopoly of the Hanseatic League in the late 15th century.

[6] Although the immediate result of this elastic supply was downward pressure on wages, it also presented an opportunity for explosive growth when aggregate consumer demand in Europe finally rebounded from the long depression, caused by the population losses of the pandemic.

Finally, the development of dikes and drainage techniques (windmills, sluices) laid the base for new forms of agriculture (dairy farming) in the maritime provinces.

By the time the Revolt erupted the disadvantages of being part of this empire (heavy taxation to finance the military adventures of the Habsburg rulers) began to outweigh the advantages of belonging to its trade network.

The word has connotations of a duty-free port, but in an economic sense, a stapelmarkt was a place where commodities were temporarily physically stocked for future reexport.

This was viable because of a legal monopoly for stockpiling a single commodity (wool), granted by a political ruler (like the staple ports designated by the kings of England in medieval times), but also more generally because of technical and economic reasons that still give certain advantages to a spoke-hub distribution paradigm.

An important ancillary function of such a physical stock of commodities is that it makes it easier for merchants to even out supply fluctuations, and hence to control price gyrations in thin and volatile markets.

More important, however, must have been the advantages of Amsterdam, which already gave it a strong position in the Baltic trades: elastic supplies of shipping and labor, low transaction costs, and efficient markets.

This mechanization was based on yet another invention of Corneliszoon, for which he received a patent in 1597: a type of crankshaft that converted the continuous rotational movement of the wind (windmill) or river (water wheel) into a reciprocating one.

Unlike rivals, it was not built for possible conversion in wartime to a warship, so it was cheaper to build and carried twice the cargo, and could be handled by a smaller crew.

Many men made and lost fortunes overnight, to the consternation of Calvinists who abhorred this artificial frenzy that denied the virtues of moderation, discretion and genuine work.

This was also a period of major land reclamation projects, the droogmakerijen of inland lakes like Beemster and Schermer that were drained by windmills and converted to polders.

Finally, there was a tremendous boom in real estate investment, ranging from the extensions of cities like Amsterdam (where the famous canal belts were built) to harbor improvements and fortifications.

[26] By the 1650s, when this boom period reached its zenith, the economy of the Republic achieved a classic harmony between its trading, industrial, agricultural, and fishing sectors, their interrelations cemented by productivity-enhancing investments.

[27] Although it is difficult to quantify concepts such as Gross domestic product and per-capita GDP in an age when reliable economic statistics were not gathered, De Vries and Van der Woude have nevertheless ventured to make a number of informed estimates, justified in their view, by the "modern" character of the Dutch economy in this period.

)[30] Besides, this type of reorientation in investment was undercut by a third response: outsourcing of industrial production to areas with a lower wage level, like the Generality Lands, which solved the high-wage problem in a different way, but also contributed to deindustrialization in the maritime provinces.

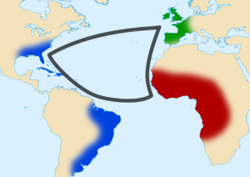

This was one of the few boom sectors of the economy in this era: the slave population in Surinam quadrupled between 1682 and 1713, and the volume of sugar shipments rose from 3 to 15 million pounds per annum.

However, this risk-taking entrepreneurialism was not rewarded with the expected higher long-term rate of return, because the expansion of each sector entailed increased exposure to international competitive forces uncompensated by the market power of the entrepot or the sources of the domestic economy.

That decline was only partially compensated by the growth of industries requiring proximity to ports, or large inputs of skilled labor (which was still in abundant supply) and fixed capital.

These revenues consisted mainly of regressive indirect taxes with the perverse effect that income was transferred from the poorer classes to the richer to the amount of 14 million guilders a year (approximately 7 percent of the Gross National Product at the time).

Ironically, such opportunities were often found in Great Britain, both in infrastructure developments, and in the British public debt that seemed as safe as the Dutch one (as these investors were very risk-averse).

Without the necessary reforms to remedy these problems the Netherlands were unlikely to participate in the industrial renaissance that Great Britain, and later other neighboring countries, started to experience in the latter part of the 18th century.

This crisis hit hardest in the cities of Holland and Zeeland, which lost 10 percent of their population between 1795 and 1815 ...Deurbanization, re-agriculturalization, and pauperization dominated the final days of this economy.