Economy of Paris

The tertiary sector, including business and financial services, government, education, and health, accounted for 90 percent of the value added, placing the Paris Region just behind Greater London and Brussels.

The largest of these, in terms of number of employees, is known in French as the QCA, or quartier central des affaires; it is in the western part of the City of Paris, in the 2nd, 8th, 9th, 16th and 18th arrondissements.

[15] Paris hosts the headquarters of Carrefour S.A., the largest food and drug store chain in France, and fourth in the world according to the 2015 Fortune Global 500, after Wal-Mart and Costco in the U.S. and Tesco in Britain.

In 1121, during the reign of Louis VI, the King accorded to the league of boatmen of Paris a fee of sixty centimes for each boatload of wine which arrived in the city during the harvest.

But by the end of the 15th century, the system of wealth had changed; the wealthiest Parisians were those who had bought land or positions in the royal administration and were close to the King.

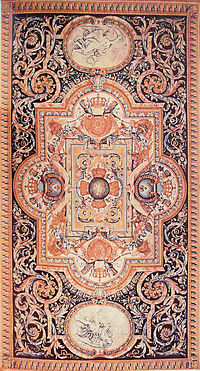

Henry IV and Louis XIII observed that wealthy Parisians were spending huge sums to import silks, tapestries, glassware leather goods and carpets from Flanders, Spain, Italy and Turkey.

The small shops in the gallery sold a wide variety of expensive gowns, cloaks, perfumes, hats, bonnets, children's wear, gloves, and other items of clothing.

Nearly all the clock and watchmakers were Protestants; when Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1685, most of the horlogers refused to renounce their faith and emigrated to Geneva, England and Holland, and France no longer dominated the industry.

The first venture of Paris into modern finance was launched by the Scottish economist John Law, who, encouraged by the Regent, in 1716 started a private bank and issued paper money.

During the Restoration, inspired by the work of the chemist Jean-Antoine Chaptal and other scientists, new factories were built along the left bank of the Seine, making a wide variety of new chemical products, but also heavily polluting the river.

Their return during the Restoration and especially the rapid growth of the number of wealthy Parisians revived the business in jewelry, furniture, fine clothing, watches and other luxury products.

It employed 1,200 workers, a large number of them women, and also included a school and laboratory, run by the École Polytechnique, to develop new methods of tobacco production.

The porcelain factory at Sèvres, which had long made table settings for the royal courts of Europe, began to make them for the bankers and industrialists of Paris.

The revolution was fuelled in large part by Paris fashions, especially the crinoline, which demanded enormous quantities of silk, satin, velour, cashmere, percale, mohair, ribbons, lace and other fabrics and decorations.

Bon Marché, was opened in 1852 by Aristide Boucicaut, the former chief of the Petit Thomas variety store, in a modest building, and expanded rapidly, its income going from 450,000 francs a year to 20 million.

Boucicaut commissioned a new building with a glass and iron framework designed in part by Gustave Eiffel, which opened in 1869, and became the model for the modern department store.

[44] The new stores pioneered new methods of marketing, from holding annual sales to giving bouquets of violets to customers or boxes of chocolates to those who spent more than 25 francs.

[45] The economy of Paris suffered an economic crisis in the early 1870s, followed by a long, slow recovery; then a period of rapid growth beginning in 1895 until the First World War.

Between 1872 and 1895, in the capital, 139 large enterprises closed their doors, particularly textile and furniture factories, those in the metallurgy sector, and printing houses, four industries which for sixty years had been the major employers in the city.

Half of the large enterprises on the center of the city's right bank moved out, in part because of the high cost of real estate, and also to get better access to transportation on the river and railroads.

Another French cinema pioneer and producer Charles Pathé, also built a studio in Montreuil, then moved to rue des Vignerons in Vincennes, east of Paris.

His chief rival in the early French film industry, Léon Gaumont, opened his first studio at about the same time at rue des Alouettes in the 19th arrondissement, near the Buttes-Chaumont.

The traditional small workshops of French industry were re-organized into huge assembly lines following the model of factory of Henry Ford in the United States and the productivity studies of Frederick Taylor on scientific management.

The low value of the Franc against the dollar made the city attractive for foreign visitors such as Ernest Hemingway, who found prices for housing and food affordable, but it was difficult for the Parisians.

He organized a series of highly publicized automobile expeditions to remote parts of Africa, Asia and Australia, and, from 1925 until 1934, had a large illuminated Citroën sign on the side of the Eiffel Tower.

The motors of the city economy were the great department stores, founded in the Belle Époque; Bon Marché, Galeries Lafayette, BHV, Printemps, La Samaritaine, and several others, grouped in the center.

As other European countries devalued their currencies to meet the crisis, French exports became too expensive, and factories cut back production and laid off workers.

World War II ruined the engines of the Paris economy; the factories, train stations and railroad yards around the city had been bombed by the Allies, there was little coal for heat, electricity was sporadic at best.

Nonetheless, the reconstruction went ahead rapidly, aided by 2.6 billion dollars in grants and loans from the United States given under the Marshall Plan between 1948 and 1953, administered locally from the Hotel Talleyrand on the Place de la Concorde, which allowed France to finance two-thirds of its exterior debt and to buy new machinery for its factories.

However, they didn't completely fulfil their role of multi-polarisation: economic activities still remain in a large measure concentrated in the central core (City of Paris and Hauts-de-Seine) of the aire urbaine, as the above employment figures show.