Edenton Tea Party

[6] In addition, it was a long-standing daily tradition of the British, and colonial social events "were defined by the amount and quality of tea provided".

[8] It was expected that women would marry and have children, and thus focus on their roles as wives and mothers over sometimes short lives, and to the exclusion of being involved in political issues.

[9] Since women would be required to find substitutes for British tea, cloth, and other taxed goods, it was crucial to have their support during the boycotts and protests organized and popularized by men.

[10] Historian Carol Berkin states, Women and girls were partners with their husbands, fathers, brothers, and sons in the public demonstrations against the new British policies and, if they were absent from the halls of the colonial legislatures, their presence was crucial in the most effective protest strategy of all: the boycott of British manufactured goods.

As we cannot be indifferent on any occasion that appears nearly to affect the peace and happiness of our country, and as it has thought necessary, for the public good, to enter into several particular resolves by a meeting of Members deputed from the whole Province, it is a duty which we owe, not only to our near and dear connections who have concurred in them, but to ourselves who are essentially interested in their welfare, to do every thing as far as lies in our power to testify our sincere adherence to the same; and we do therefore accordingly subscribe this paper, as a witness of our fixed intention and solemn determination to do so.

[21] The Edenton Resolves first appeared in the Postscript to the November 3, 1774 edition of the Virginia Gazette and then in the London newspapers throughout the following January.

An extract of a letter containing a copy of the Resolves sent to a recipient in Britain was also published in the London newspapers ahead of the October 25, 1774 statement and list of signatures.

The Provincial Deputies of North Carolina having resolved not to drink any more tea, nor wear any more British cloth, &c. many ladies of this Province have determined to give a memorable proof of their patriotism, and have accordingly entered into the following honourable and spirited association.

I send it to you, to shew your fair countrywomen, how zealously and faithfully American ladies follow the laudable example of their husbands, and what opposition your matchless Ministers may expect to receive from a people thus firmly united against them.

[25] London resident Arthur Iredell also mocks the 51 Signers' action in a letter to his brother, James (an Edenton resident), when he claims,The Edenton ladies, conscious, I suppose, of this superiority on their side, by former experience, are willing, I imagine, to crush us into atoms, by their omnipotency; the only security on our side, to prevent the impending ruin, that I can perceive, is the probability that there are but few places in America which possess so much female artillery as Edenton...[26]Despite the threat of ridicule from across the Atlantic, women who participated in protests against taxation without representation were often praised as patriots by the Colonial American press.

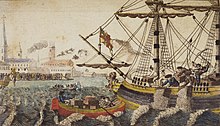

[28] A ship-load of imported East India Company tea was locked away in a port in Charles Town (now Charleston, South Carolina) for months because it could not be sold with the tax.

In 1907, Mary Dawes Staples wrote an article entitled The Edenton Tea Party, which was published by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR).