Edmund I

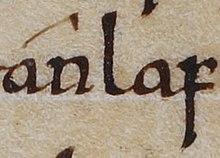

Edmund was initially forced to accept the reverse, the first major setback for the West Saxon dynasty since Alfred's reign, but he was able to recover his position following Anlaf's death in 941.

Edmund inherited his brother's interests and leading advisers, such as Oda, whom he appointed Archbishop of Canterbury in 941, Æthelstan Half-King, ealdorman of East Anglia, and Ælfheah the Bald, Bishop of Winchester.

The major religious movement of the tenth century, the English Benedictine Reform, reached its peak under Edgar, but Edmund's reign was important in its early stages.

Unlike the circle of his son Edgar, Edmund did not take the view that Benedictine monasticism was the only worthwhile religious life, and he also patronised unreformed (non-Benedictine) establishments.

In the ninth century the four Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Wessex, Mercia, Northumbria and East Anglia came under increasing attack from Vikings, culminating in invasion by the Great Heathen Army in 865.

By 878, the Vikings had overrun East Anglia, Northumbria, and Mercia, and nearly conquered Wessex, but in that year the West Saxons fought back under Alfred the Great and achieved a decisive victory at the Battle of Edington.

The twelfth-century historian William of Malmesbury gives Edmund a second full sister who married Louis, prince of Aquitaine; she was called Eadgifu, the same name as her mother.

[13] According to William of Malmesbury, Æthelstan showed great affection towards Edmund and Eadred: "mere infants at his father's death, he brought them up lovingly in childhood, and when they grew up gave them a share in his kingdom".

[16] At a royal assembly shortly before Æthelstan's death in 939, Edmund and Eadred attested a grant to their full sister, Eadburh, both as regis frater (king's brother).

[19] Brunanburh saved England from destruction as a united kingdom, and it helped to ensure that Edmund would succeed smoothly to the throne, but it did not preserve him from challenges to his rule once he became king.

This was the first serious setback for the English since Edward the Elder began to roll back Viking conquests in the early tenth century, and it was described by the historian Frank Stenton as "an ignominious surrender".

Earlier the Danes were under Northmen, subjected by force in heathens' captive fetters, for a long time until they were ransomed again, to the honour of Edward's son, protector of warriors, King Edmund.

[33] Stenton commented that the poem brings out the highly significant fact that the Danes of eastern Mercia, after fifteen years of Æthelstan's government, had come to regard themselves as the rightful subjects of the English king.

According to the thirteenth century chronicler Roger of Wendover, the invasion was supported by Hywel Dda, and Edmund had two sons of the king of Strathclyde blinded, perhaps to deprive their father of throneworthy heirs.

[46] According to the hagiography of a Gaelic monk called Cathróe, he travelled through England on his journey from Scotland to the Continent; Edmund summoned him to court and Oda, Archbishop of Canterbury, then ceremonially conducted him to his ship at Lympne.

[31] Æthelstan Half-King first witnessed a charter as an ealdorman in 932, and within three years of Edmund's accession he had been joined by two of his brothers as ealdormen; their territories covered more than half of England and his wife fostered the future King Edgar.

Ben Snook describes the charters as "impressive literary works", and like much of the writing of the period their style displays the influence of Aldhelm, a leading scholar and early eighth century bishop of Sherborne.

[73] In II Edmund, the king and his counsellors are stated to be "greatly distressed by the manifold illegal deeds of violence which are in our midst", and aimed to promote "peace and concord".

[76] In the view of the historian Dorothy Whitelock the need for legislation to control the feud was partly due to the influx of Danish settlers who believed that it was more manly to pursue a vendetta than to settle a dispute by accepting compensation.

[77] Several Scandinavian loan words are first recorded in this code, such as hamsocn, the crime of attacking a homestead; the penalty is loss of all the offender's property, while the king decides whether he also loses his life.

[84] According to a provision described by the legal historian Patrick Wormald as gruesome: "we have declared with regard to slaves that, if a number of them commit theft, their leader shall be captured and slain, or hanged, and each of the others shall be scourged three times and have his scalp removed and his little finger mutilated as a token of his guilt".

"[31] Wormald describes the codes as "an object-lesson in the variety of Anglo-Saxon legal texts", but he sees what they have in common as more important, especially a heightened rhetorical tone which extends to treating murder as an affront to the royal person.

[90] The major religious movement of the tenth century, the English Benedictine Reform, reached its peak under Edgar,[91] but Edmund's reign was important in the early stages, which were led by Oda and Ælfheah, both of whom were monks.

His men gave 60 pounds to the shrine,[q] and Edmund placed two gold bracelets on the saint's body and wrapped two costly pallia graeca (lengths of Greek cloth) around it.

[100] When Gérard of Brogne reformed the Abbey of Saint Bertin by imposing the Benedictine rule in 944, monks who rejected the changes fled to England and Edmund gave them a church owned by the crown at Bath.

He may have had personal motives for his assistance, as the monks had given burial to his half-brother, Edwin, who had drowned at sea in 933, but the incident shows that Edmund did not see only one monastic rule as valid.

[102][s] Latin learning revived in Æthelstan's reign, influenced by Continental models and by the hermeneutic style of the leading seventh century scholar and Bishop of Sherborne, Aldhelm.

"[115] In contrast, Williams describes Edmund as "an energetic and forceful ruler"[31] and Stenton commented that "he proved himself to be both warlike and politically effective",[116] while in Dumville's view, but for his early death "he might yet have been remembered as one of the more remarkable of Anglo-Saxon kings".

Trousdale sees a transition which "was marked in part by a small yet significant shift away from a reliance on traditional West Saxon administrative structures and the power blocs that had enjoyed influence under King Æthelstan, towards increased cooperation with interests and families from Mercia and East Anglia".

[122] Trousdale's picture contrasts with that of other historians such as Sarah Foot, who emphasises the achievements of Æthelstan,[123] and George Molyneaux in his study of the formation of the late Anglo-Saxon state in the reign of Edgar.