Edo society

The majority of Edo society were commoners divided into peasant, craftsmen, and merchant classes, and various "untouchable" or Burakumin groups.

[3] However, various studies have revealed since about 1995 that the classes of peasants, craftsmen, and merchants under the samurai are equal, and the old hierarchy chart has been removed from Japanese history textbooks.

The Taika Reforms were the "legal glue" deemed necessary to thwart future coup d'etat attempts, and the Ritsuryō system led to the formation of castes in Japan.

Nevertheless, frequent warfare and political instability plagued Japan in following centuries, providing countless opportunities to usurp, bend, and mobilize positions within social ranks.

Confucian ideas from China also provided the foundation for a system of strict social prescriptions, along with political twists and turns of the day.

However, Ieyasu was especially wary of social mobility given that Toyotomi Hideyoshi, one of his peers and a kampaku (Imperial Regent) whom he replaced, was born into a low caste and rose to become Japan's most powerful political figure of the time.

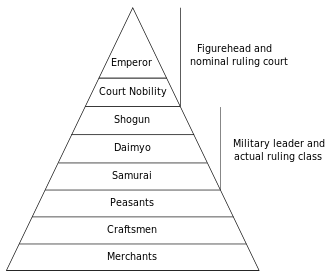

However, the Emperor was only a de jure ruler, functioning as a figurehead held up as the ultimate source of political sanction for the shōgun's authority.

The Emperor and his Imperial Court located in Kyoto, the official capital of Japan, were given virtually no political power but their prestige was invincible.

Similar to the Emperor, the kuge were incredibly prestigious and held significant influence in cultural fields, but wielded very little political power and served functions only for symbolic purposes.

Officially, the shōgun was a title for a prominent military general of the samurai class appointed by the Emperor with the task of national administration.

The shōgun was based in the Tokugawa capital city of Edo, Musashi Province, located 370 kilometres (230 mi) east of Kyoto in the Kanto region, and ruled Japan with his government, the bakufu.

The daimyō held significant autonomy but the Tokugawa policy of sankin-kōtai required them to alternate living in Edo and their domain every year.

The Tokugawa government intentionally created a social order called the Four divisions of society (shinōkōshō) that would stabilize the country.

The new four classes were based on ideas of Confucianism that spread to Japan from China, and were not arranged by wealth or capital but by what philosophers described as their moral purity.

By this system, the non-aristocratic remainder of Japanese society was composed of samurai (士, shi), farming peasants (農, nō), artisans (工, kō) and merchants (商, shō).

However, the shinōkōshō does not accurately describe Tokugawa society as Buddhist and Shinto priests, the kuge outside of the Imperial Court, and outcast classes were not included in this description of hierarchy.

In practice, solidified social relationships in general helped create the political stability that defined the Edo period.

These people were "untouchables" who fell outside of mainstream Japanese society for one reason or another, and were actively discriminated against at the societal level.

Although technically commoners, the burakumin were victims of severe ostracism and lived in their own isolated villages or ghettos away from the rest of the population.

The increasingly burdensome cost of proper social etiquette led many samurai to become indebted to wealthy urban merchant families.

New technology which increased productivity allowed some peasant families to produce a surplus of food, creating a disposable income that could be used to support ventures beyond farming.

In 1853, the beginning of the bakumatsu saw Edo society increasingly questioned by Japanese people when Western powers used their technological superiority to force concessions from the Tokugawa in the Unequal treaties.

Many Japanese people, including members of the samurai, began to blame the Tokugawa for Japan's "backwardness" and subsequent humiliation.

A modernization movement which advocated the abolition of feudalism and return of power to the Imperial Court eventually overthrew the Tokugawa Shogunate in the Meiji Restoration in 1868.