Etiquette

Recurrent thematic motifs in the maxims include learning by listening to other people, being mindful of the imperfection of human knowledge, that avoiding open conflict whenever possible should not be considered weakness, and that the pursuit of justice should be foremost.

Some of Ptahhotep's maxims indicate a person's correct behaviours in the presence of great personages (political, military, religious), and instructions on how to choose the right master and how to serve him.

Other maxims teach the correct way to be a leader through openness and kindness, that greed is the base of all evil and should be guarded against, and that generosity towards family and friends is praiseworthy.

In consequence, the ceremonious royal court favourably impressed foreign dignitaries whom the king received at the seat of French government, the Palace of Versailles, to the south-west of Paris.

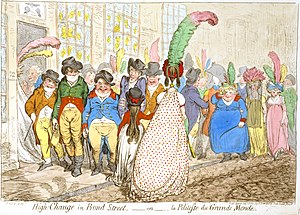

[3] In the 18th century, during the Age of Enlightenment, the adoption of etiquette was a self-conscious process for acquiring the conventions of politeness and the normative behaviours (charm, manners, demeanour) which symbolically identified the person as a genteel member of the upper class.

[5]Periodicals, such as The Spectator, a daily publication founded in 1711 by Joseph Addison and Richard Steele, regularly advised their readers on the etiquette required of a gentleman, a man of good and courteous conduct; their stated editorial goal was "to enliven morality with wit, and to temper wit with morality… to bring philosophy out of the closets and libraries, schools and colleges, to dwell in clubs and assemblies, at tea-tables and coffeehouses"; to which end, the editors published articles written by educated authors, which provided topics for civil conversation, and advice on the requisite manners for carrying a polite conversation, and for managing social interactions.

Chesterfield's elegant, literary style of writing epitomised the emotional restraint characteristic of polite social intercourse in 18th-century society: I would heartily wish that you may often be seen to smile, but never heard to laugh while you live.

I am neither of a melancholy nor a cynical disposition, and am as willing and as apt to be pleased as anybody; but I am sure that since I have had the full use of my reason nobody has ever heard me laugh.In the 19th century, Victorian era (1837–1901) etiquette developed into a complicated system of codified behaviours, which governed the range of manners in society—from the proper language, style, and method for writing letters, to correctly using cutlery at table, and to the minute regulation of social relations and personal interactions between men and women and among the social classes.

[12] In The Civilizing Process (1939), sociologist Norbert Elias said that manners arose as a product of group living, and persist as a way of maintaining social order.

[18] Public health specialist Valerie Curtis said that the development of facial responses was concomitant with the development of manners, which are behaviours with an evolutionary role in preventing the transmission of diseases, thus, people who practise personal hygiene and politeness will most benefit from membership in their social group, and so stand the best chance of biological survival, by way of opportunities for reproduction.

On Civility in Children (1530), by Erasmus of Rotterdam, instructs boys in the means of becoming a young man; how to walk and talk, speak and act in the company of adults.

The practical advice for acquiring adult self-awareness includes explanations of the symbolic meanings—for adults—of a boy's body language when he is fidgeting and yawning, scratching and bickering.

On completing Erasmus's curriculum of etiquette, the boy has learnt that civility is the point of good manners: the adult ability to 'readily ignore the faults of others, but avoid falling short, yourself,' in being civilised.

It is, in fact, only the woman who is afraid that someone may encroach upon her exceedingly insecure dignity, who shows neither courtesy nor consideration to any except those whom she considers it to her advantage to please.Etiquette and language Etiquette and letters