Effects of nuclear explosions

In general, surrounding a bomb with denser media, such as water, absorbs more energy and creates more powerful shock waves while at the same time limiting the area of its effect.

In a high-altitude burst where the density of the atmosphere is low, more energy is released as ionizing gamma radiation and X-rays than as an atmosphere-displacing shockwave.

The high temperatures and radiation cause gas to move outward radially in a thin, dense shell called "the hydrodynamic front".

The effects of a moderate rain storm during an Operation Castle nuclear explosion were found to dampen, or reduce, peak pressure levels by approximately 15% at all ranges.

Most buildings, except reinforced or blast-resistant structures, will suffer moderate damage when subjected to overpressures of only 35.5 kilopascals (kPa) (5.15 pounds-force per square inch or 0.35 atm).

Data obtained from Japanese surveys following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki found that 8 psi (55 kPa) was sufficient to destroy all wooden and brick residential structures.

The compression, vacuum and drag phases together may last several seconds or longer, and exert forces many times greater than the strongest hurricane.

The height of burst and apparent size of the fireball, a function of yield and range will determine the degree and extent of retinal scarring.

The absorbed thermal radiation raises the temperature of the surface and results in scorching, charring, and burning of wood, paper, fabrics, etc.

In Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, a tremendous firestorm developed within 20 minutes after detonation and destroyed many more buildings and homes, built out of predominantly 'flimsy' wooden materials.

It is not peculiar to nuclear explosions, having been observed frequently in large forest fires and following incendiary raids during World War II.

[17] If such a weather phenomenon as fog or haze is present at the point of the nuclear explosion, it scatters the flash, with radiant energy then reaching burn-sensitive substances from all directions.

A Faraday cage does not offer protection from the effects of EMP unless the mesh is designed to have holes no bigger than the smallest wavelength emitted from a nuclear explosion.

Large nuclear weapons detonated at high altitudes also cause geomagnetically induced current in very long electrical conductors.

Calculations demonstrate that one megaton of fission, typical of a two-megaton H-bomb, will create enough beta radiation to blackout an area 400 kilometres (250 miles) across for five minutes.

These can all be measured in most circumstances by seismic stations across the globe, and comparisons with actual earthquakes can be used to help determine estimated yield via differential analysis, by the modelling of the high-frequency (>4 Hz) teleseismic P wave amplitudes.

[24][23][25] However, theory does not suggest that a nuclear explosion of current yields could trigger fault rupture and cause a major quake at distances beyond a few tens of kilometers from the shot point.

[26] The following table summarizes the most important effects of single nuclear explosions under ideal, clear skies, weather conditions.

[27][28][29][30] Advanced computer modelling of real-world conditions and how they impact on the damage to modern urban areas has found that most scaling laws are too simplistic and tend to overestimate nuclear explosion effects.

Gamma rays from the nuclear processes preceding the true explosion may be partially responsible for the following fireball, as they may superheat nearby air and/or other material.

Within an extremely short time, perhaps a hundredth of a microsecond or so, the weapon residues consist essentially of completely and partially stripped (ionized) atoms, many of the latter being in excited states, together with the corresponding free electrons.

For an explosion in the atmosphere, the fireball quickly expands to maximum size and then begins to cool as it rises like a balloon through buoyancy in the surrounding air.

A side-effect of the Pascal-B nuclear test during Operation Plumbbob may have resulted in the first man-made object launched on an Earth escape trajectory.

The so-called "thunder well" effect from the underground explosion may have launched a metal cover plate into space at six times Earth's escape velocity, although the evidence remains subject to debate, due to aerodynamic heating likely disintegrating it before it could exit the atmosphere.

[45] Hans Bethe was assigned to study this hypothesis from the project's earliest days, and he eventually concluded that such a reaction could not sustain itself on a large scale due to cooling of the nuclear fireball through an inverse Compton effect.

[47] Nevertheless, the notion has persisted as a rumor for many years and was the source of apocalyptic gallows humor at the Trinity test where Enrico Fermi took side bets on atmospheric ignition.

[51] Fears of igniting the ocean's higher density of hydrogen, deuterium, or oxygen nuclei during American testing in the Pacific, remained a serious concern, especially as yields increased by orders of magnitude.

[59] Researchers from the University of Nicosia simulated, using high-order computational fluid dynamics, an atomic bomb explosion from a typical intercontinental ballistic missile and the resulting blast wave to see how it would affect people sheltering indoors.

Their simulated structure featured rooms, windows, doorways, and corridors and allowed them to calculate the speed of the air following the blast wave and determine the best and worst places to be.

The tight spaces can increase airspeed, and the involvement of the blast wave causes air to reflect off walls and bend around corners.

2 and N

2 ) naturally found in air. These two atmospheric gases, though generally unreactive toward each other, form NOx species when heated to excess, specifically nitrogen dioxide , which is largely responsible for the color. There was concern in the 1970s and 1980s, later proven unfounded, regarding fireball NOx and ozone loss .

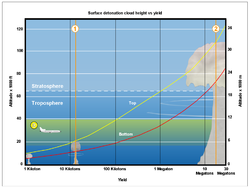

0 = Approx. altitude at which a commercial aircraft operates

1 = Fat Man

2 = Castle Bravo