Egyptian mythology

In literature, myths or elements of them were used in stories that range from humor to allegory, demonstrating that the Egyptians adapted mythology to serve a wide variety of purposes.

Each day the sun rose and set, bringing light to the land and regulating human activity; each year the Nile flooded, renewing the fertility of the soil and allowing the highly productive farming that sustained Egyptian civilization.

"[8] Much of Egyptian mythology consists of origin myths, explaining the beginnings of various elements of the world, including human institutions and natural phenomena.

The unification of Egypt under the pharaohs, at the end of the Predynastic Period around 3100 BC, made the king the focus of Egyptian religion, and thus the ideology of kingship became an important part of mythology.

[12] Egyptian sources link the mythical strife between the gods Horus and Set with a conflict between the regions of Upper and Lower Egypt, which may have happened in the late Predynastic era or in the Early Dynastic Period.

[17] Actual narratives about the gods' actions are rare in Egyptian texts, particularly from early periods, and most references to such events are mere mentions or allusions.

Some Egyptologists, like Baines, argue that narratives complete enough to be called "myths" existed in all periods, but that Egyptian tradition did not favor writing them down.

Others, like Jan Assmann, have said that true myths were rare in Egypt and may only have emerged partway through its history, developing out of the fragments of narration that appear in the earliest writings.

[18] Recently, however, Vincent Arieh Tobin[19] and Susanne Bickel have suggested that lengthy narration was not needed in Egyptian mythology because of its complex and flexible nature.

[40] Egyptologists in the early twentieth century thought that politically motivated changes like these were the principal reason for the contradictory imagery in Egyptian myth.

There are no systematic accounts of creation from ancient Egyptian literature, and so cosmological views are pieced together from a variety of brief references across different texts as well as some pictorial evidence.

[57][58] Therefore, the Egyptians conceived of the inhabited world as a bubble of air, finite and dry, surrounded by a universal and infinite, dark, formless, and inert ocean.

[61] Joanne Conman, modifying Lesko's model, argues that this solid sky is a moving, concave dome overarching a deeply convex earth.

Each day the sun rose and set, bringing light to the land and regulating human activity; each year the Nile flooded, renewing the fertility of the soil and allowing the highly productive agriculture that sustained Egyptian civilization.

These periodic events inspired the Egyptians to see all of time as a series of recurring patterns regulated by maat, renewing the gods and the universe.

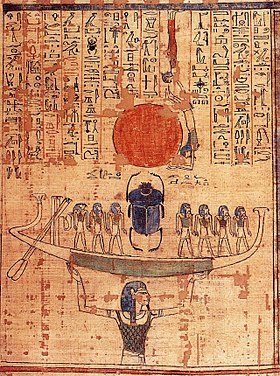

Their actions give rise to the sun (represented in creation myths by various gods, especially Ra), whose birth forms a space of light and dryness within the dark water.

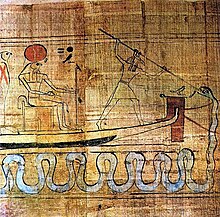

[74] Accounts from the first millennium BC focus on the actions of the creator god in subduing the forces of chaos that threaten the newly ordered world.

At the time of creation he emerges to produce other gods, resulting in a set of nine deities, the Ennead, which includes Geb, Nut, and other key elements of the world.

The Ennead can by extension stand for all the gods, so its creation represents the differentiation of Atum's unified potential being into the multiplicity of elements present within the world.

An inscription from the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1070–664 BC), whose text may be much older, describes the process in detail and attributes it to the god Ptah, whose close association with craftsmen makes him a suitable deity to give a physical form to the original creative vision.

Yet the stories about Ra's reign focus on conflicts between him and forces that disrupt his rule, reflecting the king's role in Egyptian ideology as enforcer of maat.

In an episode often called "The Destruction of Mankind", related in The Book of the Heavenly Cow, Ra discovers that humanity is plotting rebellion against him and sends his Eye to punish them.

[82] In The Book of the Heavenly Cow, the results of the destruction of mankind seem to mark the end of the direct reign of the gods and of the linear time of myth.

Egyptian accounts give sequences of divine rulers who take the place of the sun god as king on earth, each reigning for many thousands of years.

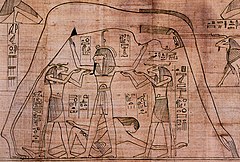

[83] Although accounts differ as to which gods reigned and in what order, the succession from Ra-Atum to his descendants Shu and Geb—in which the kingship passes to the male in each generation of the Ennead—is common.

The same theme appears in a firmly religious context in the New Kingdom, when the rulers Hatshepsut, Amenhotep III, and Ramesses II depicted in temple reliefs their own conception and birth, in which the god Amun is the father and the historical queen the mother.

Their pairing reflects the Egyptian vision of time as a continuous repeating pattern, with one member (Osiris) being always static and the other (Ra) living in a constant cycle.

This end is described in a passage in the Coffin Texts and a more explicit one in the Book of the Dead, in which Atum says that he will one day dissolve the ordered world and return to his primeval, inert state within the waters of chaos.

There are borderline cases, like a ceremony alluding to the Osiris myth in which two women took on the roles of Isis and Nephthys, but scholars disagree about whether these performances formed sequences of events.

[117] The pyramid, the best-known of all Egyptian architectural forms, may have been inspired by mythic symbolism, for it represented the mound of creation and the original sunrise, appropriate for a monument intended to assure the owner's rebirth after death.