Book of the Dead

[1] "Book" is the closest term to describe the loose collection of texts[2] consisting of a number of magic spells intended to assist a dead person's journey through the Duat, or underworld, and into the afterlife and written by many priests over a period of about 1,000 years.

In 1842, the Egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius introduced for these texts the German name Todtenbuch (modern spelling Totenbuch), translated to English as 'Book of the Dead'.

The original Egyptian name for the text, transliterated rw nw prt m hrw,[3] is translated as Spells of Coming Forth by Day.

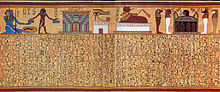

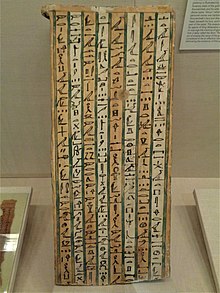

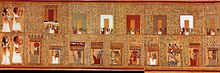

The Book of the Dead was most commonly written in hieroglyphic or hieratic script on a papyrus scroll, and often illustrated with vignettes depicting the deceased and their journey into the afterlife.

[6] Towards the end of the Old Kingdom, the Pyramid Texts ceased to be an exclusively royal privilege, and were adopted by regional governors and other high-ranking officials.

At this stage, the spells were typically inscribed on linen shrouds wrapped around the dead, though occasionally they are found written on coffins or on papyrus.

The hieratic scrolls were a cheaper version, lacking illustration apart from a single vignette at the beginning, and were produced on smaller papyri.

Most sub-texts begin with the word r(ꜣ), which can mean "mouth", "speech", "spell", "utterance", "incantation", or "chapter of a book".

[16] Others are incantations to ensure the different elements of the dead person's being were preserved and reunited, and to give the deceased control over the world around him.

[24] In fact, until Paul Barguet's 1967 "pioneering study" of common themes between texts,[25] Egyptologists concluded there was no internal structure at all.

The ka, or life-force, remained in the tomb with the dead body, and required sustenance from offerings of food, water and incense.

[35] The nature of the afterlife which the dead people enjoyed is difficult to define, because of the differing traditions within Ancient Egyptian religion.

There are also spells to enable the ba or akh of the dead to join Ra as he travelled the sky in his sun-barque, and help him fight off Apep.

These statuettes were inscribed with a spell, also included in the Book of the Dead, requiring them to undertake any manual labour that might be the owner's duty in the afterlife.

[40] These terrifying entities were armed with enormous knives and are illustrated in grotesque forms, typically as human figures with the heads of animals or combinations of different ferocious beasts.

[41] Another breed of supernatural creatures was 'slaughterers' who killed the unrighteous on behalf of Osiris; the Book of the Dead equipped its owner to escape their attentions.

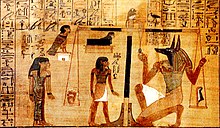

[46] At this point, there was a risk that the deceased's heart would bear witness, owning up to sins committed in life; Spell 30B guarded against this eventuality.

[47] If the heart was out of balance with Maat, then another fearsome beast called Ammit, the Devourer, stood ready to eat it and put the dead person's afterlife to an early and rather unpleasant end.

[50] Views differ among Egyptologists about how far the Negative Confession represents a moral absolute, with ethical purity being necessary for progress to the Afterlife.

John Taylor points out the wording of Spells 30B and 125 suggests a pragmatic approach to morality; by preventing the heart from contradicting him with any inconvenient truths, it seems that the deceased could enter the afterlife even if their life had not been entirely pure.

[48] Ogden Goelet says "without an exemplary and moral existence, there was no hope for a successful afterlife",[49] while Geraldine Pinch suggests that the Negative Confession is essentially similar to the spells protecting from demons, and that the success of the Weighing of the Heart depended on the mystical knowledge of the true names of the judges rather than on the deceased's moral behavior.

They were expensive items; one source gives the price of a Book of the Dead scroll as one deben of silver,[52] perhaps half the annual pay of a laborer.

[54] Most owners of the Book of the Dead were evidently part of the social elite; they were initially reserved for the royal family, but later papyri are found in the tombs of scribes, priests and officials.

The words peret em heru, or coming forth by day sometimes appear on the reverse of the outer margin, perhaps acting as a label.

Since it was found in tombs, it was evidently a document of a religious nature, and this led to the widespread but mistaken belief that the Book of the Dead was the equivalent of a Bible or Qur'an.

[62][63] In 1842 Karl Richard Lepsius published a translation of a manuscript dated to the Ptolemaic era and coined the name "Book of The Dead" (das Todtenbuch).

[65] The work of E. A. Wallis Budge, Birch's successor at the British Museum, is still in wide circulation – including both his hieroglyphic editions and his English translations of the Papyrus of Ani, though the latter are now considered inaccurate and out-of-date.

[15] In the 1970s, Ursula Rößler-Köhler at the University of Bonn began a working group to develop the history of Book of the Dead texts.

Orientverlag has released another series of related monographs, Totenbuchtexte, focused on analysis, synoptic comparison, and textual criticism.

[71] In 2023, the Ministry of Antiquities announced the finding of sections of the Book of the Dead on a 16-meter papyrus in a coffin near the Step Pyramid of Djoser.