Egyptian language

It is known today from a large corpus of surviving texts, which were made accessible to the modern world following the decipherment of the ancient Egyptian scripts in the early 19th century.

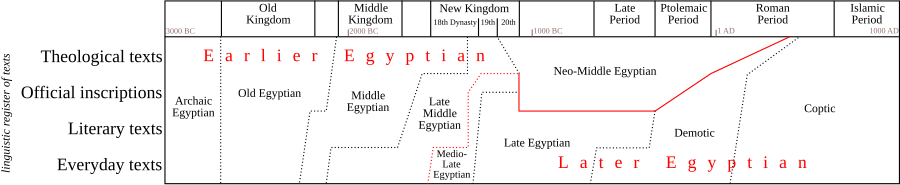

By the time of classical antiquity, the spoken language had evolved into Demotic, and by the Roman era, diversified into various Coptic dialects.

[8][9] Among the typological features of Egyptian that are typically Afroasiatic are its fusional morphology, nonconcatenative morphology, a series of emphatic consonants, a three-vowel system /a i u/, a nominal feminine suffix *-at, a nominal prefix m-, an adjectival suffix -ī and characteristic personal verbal affixes.

[9] However, other scholars have argued that the Egyptian language shared closer linguistic ties with northeastern African regions.

The term "Archaic Egyptian" is sometimes reserved for the earliest use of hieroglyphs, from the late fourth through the early third millennia BC.

From that time on, until the script was supplanted by an early version of Coptic (about the third and fourth centuries), the system remained virtually unchanged.

Middle Egyptian has been well-understood since then, although certain points of the verbal inflection remained open to revision until the mid-20th century, notably due to the contributions of Hans Jakob Polotsky.

Late Egyptian is represented by a large body of religious and secular literature, comprising such examples as the Story of Wenamun, the love poems of the Chester–Beatty I papyrus, and the Instruction of Any.

Most hieroglyphic Egyptian texts are written in a literary prestige register rather than the vernacular speech variety of their author.

[3][4] While the consonantal phonology of the Egyptian language may be reconstructed, the exact phonetics is unknown, and there are varying opinions on how to classify the individual phonemes.

[42] Phonologically, Egyptian contrasted labial, alveolar, palatal, velar, uvular, pharyngeal, and glottal consonants.

[46] In Late Egyptian (1069–700 BC), the phonemes d ḏ g gradually merge with their counterparts t ṯ k (⟨dbn⟩ */ˈdiːban/ > Akkadian transcription ti-ba-an 'dbn-weight').

Also, ṯ ḏ often become /t d/, but they are retained in many lexemes; ꜣ becomes /ʔ/; and /t r j w/ become /ʔ/ at the end of a stressed syllable and eventually null word-finally: ⟨pḏ.t⟩ */ˈpiːɟat/ > Akkadian transcription -pi-ta 'bow'.

However, the Demotic script does feature certain orthographic innovations, such as the use of the sign h̭ for /ç/,[49] which allow it to represent sounds that were not present in earlier forms of Egyptian.

The Demotic consonants can be divided into two primary classes: obstruents (stops, affricates and fricatives) and sonorants (approximants, nasals, and semivowels).

The reconstructed value of a phoneme is given in IPA transcription, followed by a transliteration of the corresponding Demotic "alphabetical" sign(s) in angle brackets ⟨ ⟩.

[55][note 5] The phoneme ⲃ /b/ was probably pronounced as a fricative [β], becoming ⲡ /p/ after a stressed vowel in syllables that had been closed in earlier Egyptian (compare ⲛⲟⲩⲃ < */ˈnaːbaw/ 'gold' and ⲧⲁⲡ < */dib/ 'horn').

[60] In the Late New Kingdom, after Ramses II, around 1200 BC, */ˈaː/ changes to */ˈoː/ (like the Canaanite shift), ⟨ḥrw⟩ '(the god) Horus' */ħaːra/ > */ħoːrə/ (Akkadian transcription: -ḫuru).

[47] Later, probably 1000–800 BC, a short stressed */ˈu/ changes to */ˈe/: ⟨ḏꜥn.t⟩ "Tanis" */ˈɟuʕnat/ was borrowed into Hebrew as *ṣuʕn but would become transcribed as ⟨ṣe-e'-nu/ṣa-a'-nu⟩ during the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

[63] Old */aː/ surfaces as /uː/ after nasals and occasionally other consonants: ⟨nṯr⟩ 'god' */ˈnaːcar/ > /ˈnuːte/ ⟨noute⟩[64] /uː/ has acquired phonemic status, as is evidenced by minimal pairs like 'to approach' ⟨hôn⟩ /hoːn/ < */ˈçaːnan/ ẖnn vs. 'inside' ⟨houn⟩ /huːn/ < */ˈçaːnaw/ ẖnw.

[66] As a convention, Egyptologists make use of an "Egyptological pronunciation" in English: the consonants are given fixed values, and vowels are inserted according to essentially arbitrary rules.

Experts have assigned generic sounds to these values as a matter of convenience, which is an artificial pronunciation and should not be mistaken for how Egyptian was ever pronounced at any time.

As the phonetic realization of Egyptian cannot be known with certainty, Egyptologists use a system of transliteration to denote each sound that could be represented by a uniliteral hieroglyph.

[76] Egyptian scholar Gamal Mokhtar noted that the inventory of hieroglyphic symbols derived from "fauna and flora used in the signs [which] are essentially African", reflecting the local wildlife of North Africa, the Levant and southern Mediterranean.

In "regards to writing, we have seen that a purely Nilotic, hence [North] African origin not only is not excluded, but probably reflects the reality" that the geographical location of Egypt is, of course, in Africa.

Vowels and other consonants are added to the root to derive different meanings, as Arabic, Hebrew, and other Afroasiatic languages still do.

However, because vowels and sometimes glides are not written in any Egyptian script except Coptic, it can be difficult to reconstruct the actual forms of words.

There are also a number of verbal endings added to the infinitive to form the stative and are regarded by some linguists[78] as a "fourth" set of personal pronouns.

Examples include: The Hebrew Bible also contains some words, terms, and names that are thought by scholars to be Egyptian in origin.

[79] Important Note: The old grammars and dictionaries of E. A. Wallis Budge have long been considered obsolete by Egyptologists, even though these books are still available for purchase.