Eighth Dynasty of Egypt

The power of the pharaohs was waning while that of the provincial governors, known as nomarchs, was increasingly important, the Egyptian state having by then effectively turned into a feudal system.

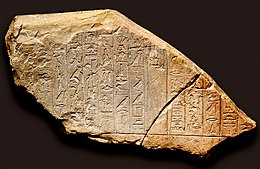

The earliest of the two and main historical source on the Eighth Dynasty is the Abydos king list, written during the reign of Seti I.

The Turin papyrus was copied from an earlier source which, as the Egyptologist Kim Ryholt has shown, was itself riddled with lacunae and must have been in a poor state.

Because the Turin papyrus omits the first nine kings on the Abydos list, W.C. Hayes thinks it reasonable that the Egyptians may have divided Dynasties VII and VIII at this point.

For example, they often contradict each other, as is the case for the two ancient historians – Sextus Julius Africanus and Eusebius of Caesarea – who quote from the section of the Aegyptiaca regarding the Seventh and Eighth Dynasties.

[13] Some of the acts of the final four Dynasty VIII kings are recorded in their decrees to Shemay, a vizier during this period, although only Qakare Ibi can be connected to any monumental construction.

Following Jürgen von Beckerath, they are : The Egyptologist Hratch Papazian believes that such a reconstruction gives too much weight to Manetho's account, according to which the Seventh Dynasty is essentially fictitious and a metaphor of chaos.

Then the Eighth Dynasty would only start with the well-attested Qakare-Ibi: In addition, the identity and chronological position and extent of rule of the following rulers is highly uncertain: Wadjkare, Khuiqer, Khui and Iytjenu.