Roman Egypt

[6] The priesthoods of the Ancient Egyptian deities and Hellenistic religions of Egypt kept most of their temples and privileges, and in turn the priests also served the Roman imperial cult of the deified emperors and their families.

[8]: 58 To the government at Alexandria besides the prefect of Egypt, the Roman emperors appointed several other subordinate procurators for the province, all of equestrian rank and, at least from the reign of Commodus (r. 176–192) of similar, "ducenarian" salary bracket.

[8]: 58 The royal scribes could act as proxy for the strategoi, but each reported directly to Alexandria, where dedicated financial secretaries – appointed for each individual nome – oversaw the accounts: an eklogistes and a graphon ton nomon.

[8]: 59 Each, to avoid conflicts of interest, was appointed to a community away from their home village, as they were required to inform the strategoi and epistrategoi of the names of persons due to perform unpaid public service as part of the liturgy system.

[9]: 71 Besides the auxilia stationed at Alexandria, at least three detachments permanently garrisoned the southern border, on the Nile's First Cataract around Philae and Syene (Aswan), protecting Egypt from enemies to the south and guarding against rebellion in the Thebaid.

[9]: 72 Besides the main garrison at Alexandrian Nicopolis and the southern border force, the disposition of the rest of the Army of Egypt is not clear, though many soldiers are known to have been stationed at various outposts (praesidia), including those defending roads and remote natural resources from attack.

[9]: 73 Archaeological work led by Hélène Cuvigny has revealed many ostraca (inscribed ceramic fragments) which give unprecedently detailed information on the lives of soldiers stationed in the Eastern Desert along the Coptos–Myos Hormos road and at the imperial granite quarry at Mons Claudianus.

The poorer people gained their livelihood as tenants of state-owned land or of property belonging to the emperor or to wealthy private landlords, and they were relatively much more heavily burdened by rentals, which tended to remain at a fairly high level.

Goods were moved around and exchanged through the medium of coin on a large scale and, in the towns and the larger villages, a high level of industrial and commercial activity developed in close conjunction with the exploitation of the predominant agricultural base.

A series of debasements of the imperial currency had undermined confidence in the coinage,[24] and even the government itself was contributing to this by demanding more and more irregular tax payments in kind, which it channelled directly to the main consumers, the army personnel.

[27]: 189 Most mētropoleis were probably built on the classical Hippodamian grid employed by the Hellenistic polis, as at Alexandria, with the typical Roman pattern of the Cardo (north–south) and Decumanus Maximus (east–west) thoroughfares meeting at their centres, as at Athribis and Antinoöpolis.

[27]: 189 Vivant Denon made sketches of ruins at Oxyrhynchus, and Edme-François Jomard wrote a description; together with some historical photographs and the few surviving remains, these are the best evidence for the classical architecture of the city, which was dedicated to the medjed, a sacred species of Mormyrus fish.

[27]: 189 Two groups of buildings survive at Heracleopolis Magna, sacred to Heracles/Hercules, which is otherwise known from Jomard's work, which also forms the mainstay of knowledge about the architecture of Antinoöpolis, founded by Hadrian in honour of his deified lover Antinous.

[30]: 438 For juridical purposes, the imperial oath recalling Ptolemaic precedent had to be sworn in the name or "fortune" (tyche) of the emperor: "I swear by Caesar Imperator, son of God, Zeus Eleutherios, Augustus".

[29]: 98 These officials, in place since the mid-1st century AD at latest, was each known as the "high priest of the Lords Augusti and all the gods" (ἀρχιερεὺς τῶν κυρίων Σεβαστῶν καὶ θεῶν ἁπάντων, archiereùs tōn kuríōn Sebastōn kaì theōn apántōn) or the "high priest of the city" (ἀρχιερεὺς τῆς πόλεως, archiereùs tēs póleōs), and was responsible mainly for the organization of the imperial cult, since the traditional local cults already had their own priesthoods.

[30]: 438 Serapis was a syncretic god of abundance and the afterlife which united Hellenistic and Egyptian features and which had been instituted by Ptolemy I Soter (r. 305/304–282 BC) at the beginning of the Ptolemaic period, possibly related to the cult of Osiris-Apis.

[32]: 439 Serapis assumed the role of Osiris in the Egyptian pantheon as god of the afterlife and regeneration, the husband of the fertility goddess Isis, and the father of the child Horus, known to the Hellenistic world as Harpocrates.

[32]: 439 The history of Egyptian temples in Roman times can be studied particularly well in some settlements at the edges of the Faiyum: Archaeological evidence, along with lots of written sources on the daily life of the priests, are available from Bakchias, Narmouthis, Soknopaiou Nesos, Tebtunis, and Theadelphia.

[31]: 14 Nerva's adoptive heir Trajan continued to lend imperial sponsorship to Egyptian cults, with his patronage recorded at Dendera, Esna, Gebelein, Kalabsha, Kom Ombo, Medinet Habu, and Philae.

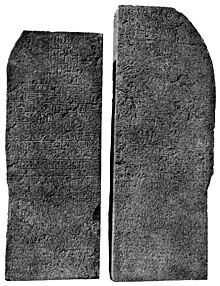

[31]: 22 At Tahta in Middle Egypt, the cartouche of Maximinus Daza was added to a since-ruined temple, along with other additions; he is the last Roman emperor known to have been recorded in official hieroglyphic script.

[36]: 475 The drive to connect Alexandria with the lives of New Testament characters was part of a desire to establish continuity and apostolic succession with the churches supposed to have been founded by Saint Peter and the other apostles.

[citation needed] The murder of the philosopher Hypatia in March 415 marked a dramatic turn in classical Hellenic culture in Egypt but philosophy thrived in sixth century Alexandria.

The first prefect of Aegyptus, Gaius Cornelius Gallus, brought Upper Egypt under Roman control by force of arms, and established a protectorate over the southern frontier district, which had been abandoned by the later Ptolemies.

[31]: 12 Under Nero, perhaps influenced by Chaeremon of Alexandria – an Egyptian priest and the emperor's Stoic tutor – an expedition to Meroë was undertaken, though possible plans for an invasion of the southern kingdom was forestalled by the military demands of the First Jewish–Roman War, a revolt in Judaea.

[31]: 14 This Diaspora Revolt meant that the Greeks and the Egyptian peasants took up arms in the fight against the Jews, which culminated in their defeat and the effective destruction of the Alexandrian Jewish community, which did not recover until the 3rd century.

[31]: 19 The emperor massacred Alexandria's welcoming delegation and allowed his army to sack the city; afterwards, he barred Egyptians from entering the place (except where for religious or trade reasons) and increased its security.

[31]: 27 On 24 February 391, the emperor Theodosius the Great (r. 379–395), in the names of himself and his co-augusti (his brother-in-law Valentinian II (r. 375–392) and his own son Arcadius (r. 383–408)) banned sacrifices and worship at temples throughout the empire in a decree addressed to Rome's praefectus urbi.

[31]: 32 Newly converted, they assisted the Roman army in its conquest of the pagan Blemmyes, and the general Narses was in 543 sent to confiscate the cult statues of Philae (which were sent to Constantinople), close the temple, and suppress its priesthood by imprisonment.

Khosrow II Parvêz had begun this war on the pretext of retaliation for the assassination of Emperor Maurice (582–602) and had achieved a series of early successes, culminating in the conquests of Jerusalem (614) and Alexandria (619).

Khosrow's son and successor, Kavadh II Šêrôe (Šêrôy), who reigned until September, concluded a peace treaty returning territories conquered by the Sassanids to the Eastern Roman Empire.