Einstein–Szilard letter

Written by Szilard in consultation with fellow Hungarian physicists Edward Teller and Eugene Wigner, the letter warned that Germany might develop atomic bombs and suggested that the United States should start its own nuclear program.

Danish physicist Niels Bohr brought the news to the United States, and the U.S. opened the Fifth Washington Conference on Theoretical Physics with Enrico Fermi on January 26, 1939.

He had first formulated and patented such an idea while he lived in London in 1933 after reading Ernest Rutherford's disparaging remarks about generating power from his team's 1932 experiment using protons to split lithium.

[2][3] Szilard collaborated with Fermi to build a nuclear reactor from natural uranium at Columbia University, where George B. Pegram headed the physics department.

Fermi and Szilard conducted a series of experiments and concluded that a chain reaction in natural uranium could be possible if they could find a suitable neutron moderator.

Another friend of Szilard's, the Austrian economist Gustav Stolper, suggested approaching Alexander Sachs, who had access to President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Sachs told Szilard that he had already spoken to the President about uranium, but that Fermi and Pegram had reported that the prospects for building an atomic bomb were remote.

That she should have taken such early action might perhaps be understood on the ground that the son of the German Under-Secretary of State, von Weizsäcker, is attached to the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut in Berlin where some of the American work on uranium is now being repeated.At the time of the letter, the estimated material necessary for a fission chain reaction was several tons.

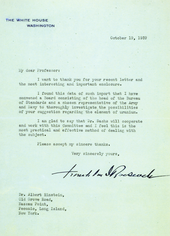

Sachs asked the White House staff for an appointment to see President Roosevelt, but before one could be set up, the administration became embroiled in a crisis due to Germany's invasion of Poland, which started World War II.

Sachs's own accounts of his meetings with Roosevelt are recounted in Brighter Than A Thousand Suns, Robert Jungk's seminal history of the development of atomic science.

Sachs managed to get an invitation to breakfast the next morning, and spent a sleepless night trying to conceive how he might persuade the president to support the plan.

This seemed to the great Corsican so impossible that he sent [Robert] Fulton away .... Had Napoleon shown more imagination and humility at that time, the history of the nineteenth century would have taken a different course.

The meeting was also attended by Fred L. Mohler from the Bureau of Standards, Richard B. Roberts of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, and Szilard, Teller and Wigner.

Adamson was skeptical about the prospect of building an atomic bomb, but was willing to authorize $6,000 ($100,000 in current USD) for the purchase of uranium and graphite for Szilard and Fermi's experiment.

[25] The Frisch–Peierls memorandum and the British Maud Reports eventually prompted Roosevelt to authorize the OSRD's secret full-scale development effort in January 1942.

The Army and Vannevar Bush denied him the work clearance needed in July 1940, saying his pacifist leanings and celebrity status made him a security risk.