Election to the Romanian throne, 1866

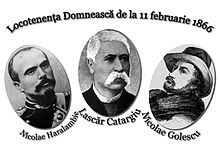

Cuza's deposition, despite his major reforms which had initiated the modernization of the Romanian principalities, had been engineered by an alliance of inherently opposed political and social forces: the "Monstrous Coalition", backed by Russia, wanted the sovereign to leave, accusing him of Caesarist tendencies.

The first candidate, Prince Philippe, Count of Flanders and brother of King Leopold II, elected before he was even informed, almost directly declined the offer made on February 23, 1866, as he had no wish to lead an "Eastern Belgium" that would be a vassal of the Ottoman Empire.

Meeting in Paris on March 10, the chancelleries of the European guarantor powers were divided over the Danube principalities, weakening the international political situation whose prospects were already clouded by the imminence of the Austro-Prussian War.

[10] Although Prince Alexandre lacked personal ascendancy, he did have the merit of choosing progressive ministers, eminent figures in Romania's cultural Renaissance, such as Vasile Alecsandri, a man of letters, Carol Davila, head of the army medical service[11] and Mihail Kogălniceanu, historian and jurist.

[12] Assisted by his Prime Minister Mihail Kogălniceanu, an intellectual leader active during the 1848 revolution, Alexandre Cuza undertook a series of reforms that contributed significantly, in a short space of time, to the modernization of Romanian society and state structures.

These measures affected almost a quarter of the useful agricultural area belonging to Orthodox monks under the monastic republic of Mount Athos or the Patriarch of Constantinople, to whom they sent a substantial part of their enormous land income.

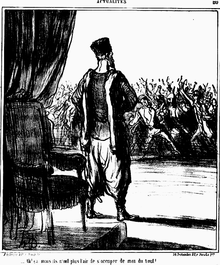

On May 14, 1864,[32] he achieved the pinnacle of his power through what some would describe as a veritable coup d'état: he dismissed the deputies of the Legislative Assembly by military force, because they refused to deliberate on the bill considerably broadening the electoral base.

[34] In June 1864, on the strength of this popular support, Cuza went to Constantinople to ask the Sultan, in agreement with the guarantor powers, to validate the new institutions he had set up: from then on, the united principalities could amend the laws governing their internal administration.

The scuffles, encouraged by domestic opposition parties and suppressed by the army, were deemed sufficiently serious (20 people were killed) to warrant an official letter from Mehmed Fuad Pasha, Ottoman Grand Vizier, requesting explanations.

On the other hand, the more radicals considered the reforms insufficient, and criticized Cuza for his propensity to accommodate the ruling classes, going so far as to compare his reign to a liberticidal dictatorship that starved the population after ruining landowners and eliminating many administrative jobs.

[38] A financial depression caused by wheat speculation, a scandal fomented by the clergy concerning his mistress Elena Maria Catargiu-Obrenović,[39] and popular discontent due to the inadequacy, but also incomprehension, of his reforms led to an unnatural connivance between conservatives and radical liberals, which Romanian humanists called the "Monstrous Coalition".

It employed subversion and propaganda, harshly criticizing Cuza's policies, and launched a systematic campaign to denigrate the Romanian government through its diplomats and newspapers (such as the Journal de Saint-Pétersbourg, Russky Invalid and Moskovskiye Vedomosti).

[46] Article 13 of the 1858 Paris Conference stipulated that anyone aged thirty-five and the son of a Moldavian or Wallachian-born father could be elected to the Hospodorate, provided they had held public office for ten years or were a member of the Assemblies.

[48] However, in the eyes of the provisional government, the choice of a foreign prince appeared to be the best option, but by entrusting the fate of their country to the protecting powers, the Romanian patriots were implicitly jeopardizing the fragile gains of the previous decade.

[53] As soon as the news of this election became known, the Journal de Saint-Pétersbourg, the unofficial organ of the Russian Foreign Ministry, published an editorial pretending to regret Cuza's fall and advising the Count of Flanders to await the decision of the diplomatic conference scheduled to meet on the future of the Danube principalities.

Unofficially, Russia gave its agents a threefold mission: to ensure that the provisional government did not exceed the remit of a local police force, to exert no pressure on those who wished to return to the old order of things, and to provide underhand encouragement to the separatist party.

Blondeel was suspected of wanting to unite Moldavia and Wallachia, with the help of Jacques Poumay, Belgian consul in Bucharest, and of supporting the idea of electing Philippe de Belgique, who received the information on March 23, 1857.

[61] From a European economic point of view, the continuing uncertainty in Romania led to a fall in London stock market prices, as Great Britain had given substantial material support to the principalities by committing capital for the creation of roads and bridges, and access to cheap waterways for the trade.

[62] From a military point of view, tension increased around the Romanian provinces: the Sultan asked the powers that had signed the Treaty of Paris for authorization to intervene in the Danube principalities, while six Cossack regiments reinforced the Russian observation army stationed on the Moldavian border.

[64] In Great Britain, William Ewart Gladstone announced to the House of Commons on March 7 that his country, the Sublime Porte and the Protecting Powers would be meeting in conference to discuss the Romanian situation; but he already warned his partners that the clauses of the 1856 Treaty of Paris must be respected.

[65] The conference of ambassadors appointed to settle the principalities issue opened in Paris on March 10, and met five times until April 5 under the chairmanship of Édouard Drouyn de Lhuys, the French Foreign Minister, as he represented the host country.

[41] The obstinacy of Russia (represented in Paris by Baron Andreas von Budberg, who received instructions from Foreign Minister Alexander Gortchakov) in insisting on the separation of the principalities irritated Great Britain, which considered that the Romanian provisional government would eventually impose its views thanks to the support of France, Prussia and Italy.

[68] The inaction and indecision of the conference encouraged the Romanian provisional government, whose view that the Chambers, elected under Cuza's regime, could no longer legitimately represent the true ideas of the country, led it to dissolve them on March 30 to have a free hand.

However, it was only on June 25, after receiving a note from Gortchakov inviting Great Britain to join Russia in maintaining peace in the Balkans, that Budberg proposed to Drouyn de Lhuys the official closure of the conference, which then ceased to meet.

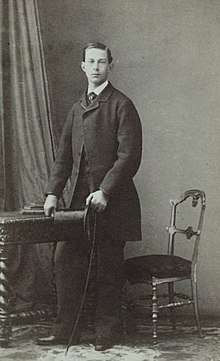

[69] Ion Brătianu, one of the liberal leaders who had brought about Cuza's downfall, established secret contacts in Paris with Napoleon III, which led to the candidacy of Charles de Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, second son of Prince Charles-Antoine, formerly Minister-President of Prussia, still very influential in Germany and whose family was partly of French descent.

[71] Charles de Hohenzollern was not only an accomplished military man who had taken part in the decisive Duchy War victory at Dybbøl, but also a former student of Bonn University, where he had studied French history and literature.

[75] Informed of this electoral success, and of the King of Prussia's positive response, received on April 16, Otto von Bismarck (then Prussian Foreign Minister) suggested that Prince Charles, now determined to try his hand at adventure, should request leave from his dragoon regiment and travel directly to the Danube principalities, to inaugurate his reign.

[80][81] After more than three hours of rioting, Rosetti-Roznovanu, Metropolitan Miclescu (who sounded the tocsin during the scuffles and was wounded)[82] and other conspirators, such as Constantin D. Moruzi, a Moldavian boyar and dregător (chancellor) of Russian origin,[83] were arrested and taken before the Minister of War, who imprisoned them.

[76] On May 2, the Paris Conference for the Affairs of the Danube Principalities ordered a new election to be organized by the Romanian Chamber, but the latter almost unanimously reiterated the choice of the Prince of Hohenzollern expressed in the plebiscite of April 20.

At 4 p.m., after having to jostle a captain who pointed out that his ticket was stamped for Odessa and wanted to prevent him from disembarking, Charles steps onto Romanian soil for the first time in the small port town of Drobeta-Turnu Severin.