Electromagnetism

Electric forces also allow different atoms to combine into molecules, including the macromolecules such as proteins that form the basis of life.

Many ancient civilizations, including the Greeks and the Mayans, created wide-ranging theories to explain lightning, static electricity, and the attraction between magnetized pieces of iron ore.

However, it was not until the late 18th century that scientists began to develop a mathematical basis for understanding the nature of electromagnetic interactions.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, prominent scientists and mathematicians such as Coulomb, Gauss and Faraday developed namesake laws which helped to explain the formation and interaction of electromagnetic fields.

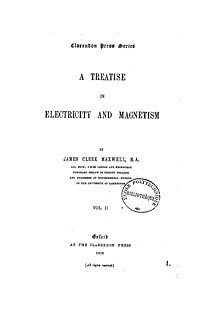

Maxwell's equations provided a sound mathematical basis for the relationships between electricity and magnetism that scientists had been exploring for centuries, and predicted the existence of self-sustaining electromagnetic waves.

The theoretical implications of electromagnetism, particularly the requirement that observations remain consistent when viewed from various moving frames of reference (relativistic electromagnetism) and the establishment of the speed of light based on properties of the medium of propagation (permeability and permittivity), helped inspire Einstein's theory of special relativity in 1905.

In QED, changes in the electromagnetic field are expressed in terms of discrete excitations, particles known as photons, the quanta of light.

There is evidence that the ancient Chinese,[1] Mayan,[2][3] and potentially even Egyptian civilizations knew that the naturally magnetic mineral magnetite had attractive properties, and many incorporated it into their art and architecture.

that amber could acquire an electric charge when it was rubbed with cloth, which allowed it to pick up light objects such as pieces of straw.

Despite all this investigation, ancient civilizations had no understanding of the mathematical basis of electromagnetism, and often analyzed its impacts through the lens of religion rather than science (lightning, for instance, was considered to be a creation of the gods in many cultures).

This view changed with the publication of James Clerk Maxwell's 1873 A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism[6] in which the interactions of positive and negative charges were shown to be mediated by one force.

There are four main effects resulting from these interactions, all of which have been clearly demonstrated by experiments: In April 1820, Hans Christian Ørsted observed that an electrical current in a wire caused a nearby compass needle to move.

They influenced French physicist André-Marie Ampère's developments of a single mathematical form to represent the magnetic forces between current-carrying conductors.

This unification, which was observed by Michael Faraday, extended by James Clerk Maxwell, and partially reformulated by Oliver Heaviside and Heinrich Hertz, is one of the key accomplishments of 19th-century mathematical physics.

On this the whole number was tried, and found to do the same, and that, to such a degree as to take up large nails, packing needles, and other iron things of considerable weight ...E. T. Whittaker suggested in 1910 that this particular event was responsible for lightning to be "credited with the power of magnetizing steel; and it was doubtless this which led Franklin in 1751 to attempt to magnetize a sewing-needle by means of the discharge of Leyden jars.

[22][23] One of the first to discover and publish a link between human-made electric current and magnetism was Gian Romagnosi, who in 1802 noticed that connecting a wire across a voltaic pile deflected a nearby compass needle.

[24] Ørsted's work influenced Ampère to conduct further experiments, which eventually gave rise to a new area of physics: electrodynamics.

By determining a force law for the interaction between elements of electric current, Ampère placed the subject on a solid mathematical foundation.

According to Maxwell's equations, the speed of light in vacuum is a universal constant that is dependent only on the electrical permittivity and magnetic permeability of free space.

One way to reconcile the two theories (electromagnetism and classical mechanics) is to assume the existence of a luminiferous aether through which the light propagates.