Electric fish

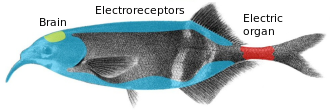

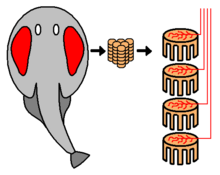

This is made up of electrocytes, modified muscle or nerve cells, specialized for producing strong electric fields, used to locate prey, for defence against predators, and for signalling, such as in courtship.

[1] Cartilaginous fishes and some other basal groups use passive electrolocation with sensors that detect electric fields;[2] the platypus and echidna have separately evolved this ability.

Finally, fish in several groups have the ability to deliver electric shocks powerful enough to stun their prey or repel predators.

These evolved from the mechanical sensors of the lateral line, and exist in cartilaginous fishes (sharks, rays, and chimaeras), lungfishes, bichirs, coelacanths, sturgeons, paddlefish, aquatic salamanders, and caecilians.

Where electroreception does occur in these groups, it has secondarily been acquired in evolution, using organs other than and not homologous with ampullae of Lorenzini.

[8] In Gymnarchus niloticus (the African knifefish), the tail, trunk, hypobranchial, and eye muscles are incorporated into the organ, most likely to provide rigid fixation for the electrodes while swimming.

This may reduce lateral bending while swimming, allowing the electric field to remain stable for electrolocation.

[9][10] Actively electrolocating fish are marked on the phylogenetic tree with a small yellow lightning flash .

These are too weak to stun prey and instead are used for navigation, electrolocation in conjunction with electroreceptors in their skin, and electrocommunication with other electric fish.

[17] Electric eels sometimes leap out of the water to electrify possible predators directly, as has been tested with a human arm.

[17] The amplitude of the electrical output from these fish can range from 10 to 860 volts with a current of up to 1 ampere, according to the surroundings, for example different conductances of salt and freshwater.

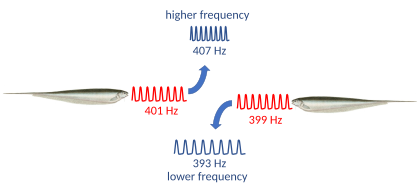

[15] Electric organ discharges (EODs) need to vary with time for electrolocation, whether with pulses, as in the Mormyridae, or with waves, as in the Torpediniformes and Gymnarchus, the African knifefish.

The cost to males is reduced by a circadian rhythm, with more activity coinciding with night-time courtship and spawning, and less at other times.

The electroreceptive African sharptooth catfish (Clarias gariepinus) may hunt the weakly electric mormyrid, Marcusenius macrolepidotus in this way.

[30] This has driven the prey, in an evolutionary arms race, to develop more complex or higher frequency signals that are harder to detect.

[32][25] A similar jamming avoidance response was discovered in the distantly related Gymnarchus niloticus, the African knifefish, by Walter Heiligenberg in 1975, in a further example of convergent evolution between the electric fishes of Africa and South America.