Electric eel

The electric eels are a genus, Electrophorus, of neotropical freshwater fish from South America in the family Gymnotidae.

They are nocturnal, obligate air-breathing animals, with poor vision complemented by electrolocation; they mainly eat fish.

[7] The name is from the Greek ήλεκτρον (ḗlektron 'amber, a substance able to hold static electricity'), and φέρω (phérō 'I carry'), giving the meaning 'electricity bearer'.

[11] In 1998, Albert and Campos-da-Paz lumped the Electrophorus genus with the family Gymnotidae, alongside Gymnotus,[12] as did Ferraris and colleagues in 2017.

[8][2] In 2019, C. David de Santana and colleagues divided E. electricus into three species based on DNA divergence, ecology and habitat, anatomy and physiology, and electrical ability.

[13] The lowland region of E. varii is a variable environment, with habitats ranging from streams through grassland and ravines to ponds, and large changes in water level between the wet and dry seasons.

[29][32] This enables them to live in habitats with widely varying oxygen levels including streams, swamps, and pools.

[12][33] About every two minutes, the fish takes in air through the mouth, holds it in the buccal cavity, and expels it through the opercular openings at the sides of the head.

[29][35] They are capable of hearing via a Weberian apparatus, which consists of tiny bones connecting the inner ear to the swim bladder.

[38] Electric eels use their high frequency-sensitive tuberous receptors, distributed in patches over the body, for hunting other knifefish.

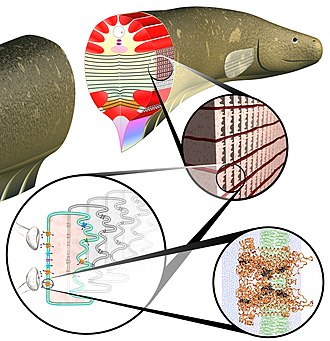

[42][43] These organs are also rich in sodium potassium ATPase, an ion pump used to create a potential difference across cell membranes.

[45] Freshwater fishes like the electric eel require a high voltage to give a strong shock because freshwater has high resistance; powerful marine electric fishes like the torpedo ray give a shock at much lower voltage but a far higher current.

The electric eel produces its strong discharge extremely rapidly, at a rate of as much as 500 Hertz, meaning that each shock lasts only about two milliseconds.

[46] The ability to produce high-voltage, high-frequency pulses in addition enables the electric eel to electrolocate rapidly moving prey.

In 2021, Jun Xu and colleagues stated that Hunter's organ produces a third type of discharge at a middle voltage of 38.5 to 56.5 volts.

Spawn hatch seven days later and mothers keep depositing eggs periodically throughout the breeding season, making them fractional spawners.

[54] The first written mention of the electric eel or puraké ('the one that numbs' in Tupi) is in records by the Jesuit priest Fernão Cardim in 1583.

[4][5] Hunter informed the Royal Society that "Gymnotus Electricus [...] appears very much like an eel [...] but it has none of the specific properties of that fish.

[5] Also in 1775, the American physician and politician Hugh Williamson, who had studied with Hunter,[57] presented a paper "Experiments and observations on the Gymnotus Electricus, or electric eel" at the Royal Society.

"[58] The studies by Williamson, Walsh, and Hunter appear to have influenced the thinking of Luigi Galvani and Alessandro Volta.

[4][59] In 1800, the explorer Alexander von Humboldt joined a group of indigenous people who went fishing with horses, some thirty of which they chased into the water.

The electric eels, having given many shocks, "now require long rest and plenty of nourishment to replace the loss of galvanic power they have suffered", "swam timidly to the bank of the pond", and were easily caught using small harpoons on ropes.

For a span of four months, he measured the electrical impulses produced by the animal by pressing shaped copper paddles and saddles against the specimen.

The German zoologist Carl Sachs was sent to Latin America by the physiologist Emil du Bois-Reymond, to study the electric eel;[62] he took with him a galvanometer and electrodes to measure the fish's electric organ discharge,[63] and used rubber gloves to enable him to catch the fish without being shocked, to the surprise of the local people.

[49][63] The large quantity of electrocytes available in the electric eel enabled biologists to study the voltage-gated sodium channel in molecular detail.

They suggest that such artificial electrocytes could be developed as a power source for medical implants such as retinal prostheses and other microscopic devices.

[64] In 2016, Hao Sun and colleagues described a family of electric eel-mimicking devices that serve as high output voltage electrochemical capacitors.

Sun and colleagues suggest that the storage devices could serve as power sources for products such as electric watches or light-emitting diodes.