Electromagnetic acoustic transducer

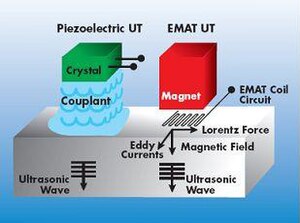

Its effect is based on electromagnetic mechanisms, which do not need direct coupling with the surface of the material.

Due to this couplant-free feature, EMATs are particularly useful in harsh, i.e., hot, cold, clean, or dry environments.

[1][2][3] After decades of research and development, EMAT has found its applications in many industries such as primary metal manufacturing and processing, automotive, railroad, pipeline, boiler and pressure vessel industries,[3] in which they are typically used for nondestructive testing (NDT) of metallic structures.

According to the theory of electromagnetic induction, the distribution of the eddy current is only at a very thin layer of the material, called skin depth.

Typically for 1 MHz AC excitation, the skin depth is only a fraction of a millimeter for primary metals like steel, copper and aluminum.

In a macroscopic view, the Lorentz force is applied on the surface region of the material due to the interaction between electrons and atoms.

The distribution of Lorentz force is primarily controlled by the design of magnet and design of the electric coil, and is affected by the properties of the test material, the relative position between the transducer and the test part, and the excitation signal for the transducer.

The spatial distribution of the Lorentz force determines the precise nature of the elastic disturbances and how they propagate from the source.

The magnetostriction effect has been used to generate both SH-type and Lamb type waves in steel products.

In addition to the above-mentioned applications, which fall under the category of nondestructive testing, EMATs have been used in research for ultrasonic communication, where they generate and receive an acoustic signal in a metallic structure.