Calutron

During World War II, calutrons were developed to use this principle to obtain substantial quantities of high-purity uranium-235, by taking advantage of the small mass difference between uranium isotopes.

Electromagnetic separation for uranium enrichment was abandoned in the post-war period in favor of the more complicated, but more efficient, gaseous diffusion method.

Although most of the calutrons of the Manhattan Project were dismantled at the end of the war, some remained in use to produce isotopically enriched samples of naturally occurring elements for military, scientific and medical purposes.

[1] Based on his liquid drop model of the nucleus, he theorized that it was the uranium-235 isotope and not the more abundant uranium-238 that was primarily responsible for fission with thermal neutrons.

[3][4] Leo Szilard and Walter Zinn soon confirmed that more than one neutron was released per fission, which made it almost certain that a nuclear chain reaction could be initiated, and therefore that the development of an atomic bomb was a theoretical possibility.

[6] At the University of Birmingham in Britain, the Australian physicist Mark Oliphant assigned two refugee physicists—Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls—the task of investigating the feasibility of an atomic bomb, ironically because their status as enemy aliens precluded their working on secret projects like radar.

[9] Britain had offered to give the United States access to its scientific research,[10] so the Tizard Mission's John Cockcroft briefed American scientists on British developments.

The reason the Maud Committee, and later its American counterpart, the S-1 Section of the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), had passed over the electromagnetic method was that while the mass spectrometer was capable of separating isotopes, it produced very low yields.

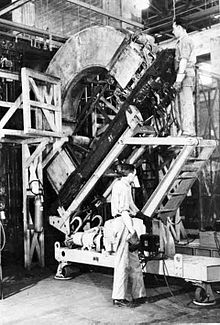

[21][22] When the calutron was first operated on 2 December 1941, just days before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into World War II, a uranium beam intensity of 5 microamperes (μA) was received by the collector.

[18] At Cornell University a group under Lloyd P. Smith that included William E. Parkins, and A. Theodore Forrester devised a radial magnetic separator.

Lawrence assembled a team of physicists to tackle the problems, including David Bohm,[26] Edward Condon, Donald Cooksey,[27] A. Theodore Forrester,[28] Irving Langmuir, Kenneth Ross MacKenzie, Frank Oppenheimer, J. Robert Oppenheimer, William E. Parkins, Bernard Peters and Joseph Slepian.

The operator sat in the open end, whence the temperature could be regulated, the position of the electrodes adjusted, and even components replaced through an airlock while it was running.

Their papers on the properties of plasmas under magnetic containment would find usage in the post-war world in research into controlled nuclear fusion.

Charles A. Kraus proposed a better method for large-scale production that involved reacting the uranium oxide with carbon tetrachloride at high temperature and pressure.

His staff put in long hours, and University of California administrators sliced through red tape despite not knowing what the project was about.

Government officials began to view the development of atomic bombs in time to affect the outcome of the war as a genuine possibility.

Vannevar Bush, the director of the OSRD, which was overseeing the project, visited Berkeley in February 1942, and found the atmosphere there "stimulating" and "refreshing".

[44] On 9 March 1942, he reported to the president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, that it might be possible to produce enough material for a bomb by mid-1943, based on new estimates from Robert Oppenheimer that the critical mass of a sphere of pure uranium-235 was between 2.0 and 2.5 kilograms.

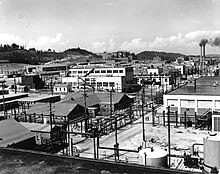

[48] The Shasta Dam area in California remained under consideration for the electromagnetic plant until September 1942, by which time Lawrence had dropped his objection.

[52] Major Thomas T. Crenshaw, Jr., became California Area Engineer in August 1942, with Captain Harold A. Fidler, who soon replaced him, as his assistant.

[56] The Radiation Laboratory forwarded the preliminary designs for a production plant to Stone & Webster before the end of the year, but one important issue remained unsettled.

Some 258 carloads were shipped under guard by rail to Allis-Chalmers in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where they were wound onto magnetic coils and sealed into welded casings.

When the first racetrack was started up for testing on schedule in November, the 14-ton vacuum tanks crept out of alignment by as much as 3 inches (8 cm) because of the power of the magnets and had to be fastened more securely.

Work started on the new Alpha II process buildings on 2 November 1943; the first racetrack was completed in July 1944, and all four were operational by 1 October 1944.

They agreed to a production race and Lawrence lost, a morale boost for the "Calutron Girls" (called Cubicle Operators at the time) and their supervisors.

The women were trained like soldiers not to reason why, while "the scientists could not refrain from time-consuming investigation of the cause of even minor fluctuations of the dials".

Frank Spedding from the Manhattan Project's Ames Laboratory and Philip Baxter from the British Mission were sent to advise on improvements to recovery methods.

[90][91] In 1947, Eugene Wigner, the director of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), asked the Atomic Energy Commission for permission to use the Beta calutrons to produce isotopes for physics experiments.

[96][98][99] Four research and production calutrons were built at the China Institute of Atomic Energy in Beijing of identical design to those of the USSR in the early 1960s.

The 180° design was not ideal for this purpose, so Harwell built a 90° calutron, HERMES, the "Heavy Elements and Radioactive Material Electromagnetic Separator".