Electrostatic induction

[1] Induction was discovered by British scientist John Canton in 1753 and Swedish professor Johan Carl Wilcke in 1762.

Due to induction, the electrostatic potential (voltage) is constant at any point throughout a conductor.

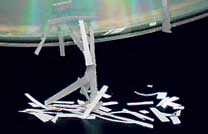

[3] Electrostatic induction is also responsible for the attraction of light nonconductive objects, such as balloons, paper or styrofoam scraps, to static electric charges.

Electrostatic induction laws apply in dynamic situations as far as the quasistatic approximation is valid.

A normal uncharged piece of matter has equal numbers of positive and negative electric charges in each part of it, located close together, so no part of it has a net electric charge.

[4]: p.711–712 The positive charges are the atoms' nuclei which are bound into the structure of matter and are not free to move.

When the electrons move out of an area, they leave an unbalanced positive charge due to the nuclei.

When the contact with ground is broken, the object is left with a net negative charge.

This method can be demonstrated using a gold-leaf electroscope, which is an instrument for detecting electric charge.

The electroscope is first discharged, and a charged object is then brought close to the instrument's top terminal.

[5] The two rules of induction are:[5][6] A remaining question is how large the induced charges are.

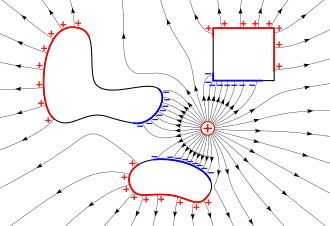

As the charges in the metal object continue to separate, the resulting positive and negative regions create their own electric field, which opposes the field of the external charge.

[3] This process continues until very quickly (within a fraction of a second) an equilibrium is reached in which the induced charges are exactly the right size and shape to cancel the external electric field throughout the interior of the metal object.

[3] Since the mobile charges (electrons) in the interior of a metal object are free to move in any direction, there can never be a static concentration of charge inside the metal; if there was, it would disperse due to its mutual repulsion.

[3] The electrostatic potential or voltage between two points is defined as the energy (work) required to move a small positive charge through an electric field between the two points, divided by the size of the charge.

: Since there can be no electric field inside a conductive object to exert force on charges

A similar induction effect occurs in nonconductive (dielectric) objects, and is responsible for the attraction of small light nonconductive objects, like balloons, scraps of paper or Styrofoam, to static electric charges[8][9][10] (see picture of cat, above), as well as static cling in clothes.

This effect is microscopic, but since there are so many molecules, it adds up to enough force to move a light object like Styrofoam.

This should not be confused with a polar molecule, which has a positive and negative end due to its structure, even in the absence of external charge.