Lymphatic filariasis

[2][3] Usually acquired in childhood, it is a leading cause of permanent disability worldwide, impacting over a hundred million people and manifesting itself in a variety of severe clinical pathologies[6][7] While most cases have no symptoms, some people develop a syndrome called elephantiasis, which is marked by severe swelling in the arms, legs, breasts, or genitals.

[2] Most people infected with the worms that cause lymphatic filariasis never develop symptoms;[12] though some have damage to lymph vessels that can be detected by medical ultrasound.

[13] Months to years after the initial infection, the worms die, triggering an immune response that manifests with repeated episodes of fever and painful swelling over the nearest lymph nodes (typically those along the groin).

Dysfunctional vessels fail to recirculate lymph fluid, which can pool (called lymphodema) in the nearest extremity – generally the arm, leg, breast, or scrotum.

[14] Even those without lymph damage can sometimes develop an allergic reaction to the worm larvae in the capillaries of the lung, called tropical pulmonary eosinophilia.

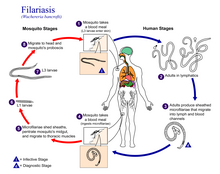

Inside the mosquito, the microfilariae pierce the stomach wall and crawl to the flight muscles, where they mature over 10 to 20 days into their human-infectious form.

The adult worms live in the human lymphatic system and obstruct the flow of lymph throughout the body; this results in chronic lymphedema, most often noted in the lower torso (typically in the legs and genitals).

[23] Lymphatic filariasis may be confused with podoconiosis (also known as nonfilarial elephantiasis), a non-infectious disease caused by exposure of bare feet to irritant alkaline clay soils.

Insect repellents and mosquito nets (especially when treated with an insecticide such as deltamethrin or permethrin)[26] have been demonstrated to reduce the transmission of lymphatic filariasis.

Because the parasite requires a human host to reproduce, consistent treatment of at-risk populations (annually for a duration of four to six years)[2] is expected to break the cycle of transmission and cause the extinction of the causative organisms.

[31] Treatment of lymphatic filariasis depends in part on the geographic location of the area of the world in which the disease was acquired but often involves the combination of two or more anthelmintic agents: albendazole, ivermectin, and diethylcarbamazine.

Albendazole monotherapy is used in regions with endemic loiasis in combination with integrated vector control and was the treatment modality for 11.2 million people in 2022.

[11] Wolbachia are endosymbiotic bacteria that live inside the gut of the nematode worms responsible for lymphatic filariasis, and which provide nutrients necessary for their survival.

Limitations of this antibiotic protocol include that it requires 4 to 6 weeks of treatment rather than the single dose of the anthelmintic agents, that doxycycline should not be used in young children and pregnant women, and that it is phototoxic.

[37] Acute inflammatory responses due to lymphedema, and hydrocele can be reduced or prevented by practicing good hygiene, skin care, exercise and elevation of infected limbs.

[5] W. bancrofti largely affects areas across the broad equatorial belt (Africa, the Nile Delta, Turkey, India, the East Indies, Southeast Asia, Philippines, Oceanic Islands, and parts of South America).

Since lymphatic filariasis requires multiple mosquito bites over several months to years to spread of infection due to tourism is low.

[39] Lymphatic Filariasis is extremely uncommon in the United States, with only one reported case found in South Carolina in the early 1900s.

[7] In South America, four endemic countries have been working to beset lymphatic filariasis, consisting of Brazil, the Dominican Republic, Guyana, and Haiti.

[40] Brazil targeted the rising endemic by administering DEC drugs through an MDA program to the communities hit hardest by the disease.

In communities where lymphatic filariasis is endemic, as many as 10% of women can be affected by swollen limbs, and 50% of men can develop mutilating genital symptoms.

Similar symptoms were reported by subsequent explorers in areas of Asia and Africa, though an understanding of the disease did not begin to develop until centuries later.

[47] In 1866, Timothy Lewis, building on the work of Jean Nicolas Demarquay [de] and Otto Henry Wucherer, made the connection between microfilariae and elephantiasis, establishing the course of research that would ultimately explain the disease.

[49] In 1900, George Carmichael Low determined the actual transmission method by discovering the presence of the worm in the proboscis of the mosquito vector.

This is called pericaes in the native language, and all the swelling is the same from the knees downward, and they have no pain, nor do they take any notice of this infirmity.Researchers at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) have developed a novel vaccine for the prevention of lymphatic filariasis.

This vaccine has been shown to elicit strong, protective immune responses in mouse models of lymphatic filariasis infection.

The immune response elicited by this vaccine has been demonstrated to be protective against both W. bancrofti and B. malayi infection in the mouse model and may prove useful in the human.

[51] On 20 September 2007, geneticists published the first draft of the complete genome (genetic content) of Brugia malayi, one of the roundworms that causes lymphatic filariasis.