Elizabeth Cady Stanton

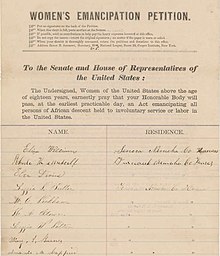

During the American Civil War, they established the Women's Loyal National League to campaign for the abolition of slavery, and they led it in the largest petition drive in U.S. history up to that time.

[3] Her mother, Margaret Cady (née Livingston), was more progressive, supporting the radical Garrisonian wing of the abolitionist movement and signing a petition for women's suffrage in 1867.

[8][9] She was made sharply aware of society's low expectations for women when Eleazar, her last surviving brother, died at the age of 20 just after graduating from Union College in Schenectady, New York.

[9] In her memoirs, Stanton said that during her student days in Troy she was greatly disturbed by a six-week religious revival conducted by Charles Grandison Finney, an evangelical preacher and a central figure in the revivalist movement.

Smith was an abolitionist and a member of the "Secret Six," a group of men who financed John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry in an effort to spark an armed uprising of enslaved African Americans.

[40] Although this was a local convention organized on short notice, its controversial nature ensured that it was widely noted in the press, with articles appearing in newspapers in New York City, Philadelphia and many other places.

In 1871, Anthony said, "whoever goes into a parlor or before an audience with that woman does it at the cost of a fearful overshadowing, a price which I have paid for the last ten years, and that cheerfully, because I felt that our cause was most profited by her being seen and heard, and my best work was making the way clear for her.

"[62] She attacked the religious establishment, calling for women to donate their money to the poor instead of to the "education of young men for the ministry, for the building up a theological aristocracy and gorgeous temples to the unknown God.

[citation needed] In 1853, Susan B. Anthony organized a petition campaign in New York state for an improved property rights law for married women.

It was soon adopted by many female reform activists despite harsh ridicule from traditionalists, who considered the idea of women wearing any sort of trousers as a threat to the social order.

The speaker describes the horrors of slavery, saying, "The trembling girl for whom thou didst pay a price but yesterday in a New Orleans market, is not thy lawful wife.

[90] In the largest petition drive in the nation's history up to that time, the League collected nearly 400,000 signatures to abolish slavery, representing approximately one out of every twenty-four adults in the Northern states.

[96] Its 5000 members constituted a widespread network of women activists who gained experience that helped create a pool of talent for future forms of social activism, including suffrage.

Anthony and Stanton created a storm of controversy by accepting help during the last days of the campaign from George Francis Train, a wealthy businessman who supported women's rights.

One wing, whose leading figure was Lucy Stone, was willing for black men to achieve suffrage first and wanted to maintain close ties with the Republican Party and the abolitionist movement.

Initial funding was provided by George Francis Train, the controversial businessman who supported women's rights but who alienated many activists with his political and racial views.

[147] Stanton later teased Anthony, saying, "Well, as all women are supposed to be under the thumb of some man, I prefer a tyrant of my own sex, so I shall not deny the patent fact of my subjection.

"[148] The convention succeeded in bringing increased publicity and respectability to the women's movement, especially when President Grover Cleveland honored the delegates by inviting them to a reception at the White House.

[citation needed] Stanton and Anthony encouraged their rival Lucy Stone to assist with the work, or at least to send material that could be used by someone else to write the history of her wing of the movement, but she refused to cooperate in any way.

This organization was part of the Lyceum movement, which arranged for speakers and entertainers to tour the country, often visiting small communities where educational opportunities and theaters were scarce.

While living in Boston in the 1840s, she was attracted to the preaching of Theodore Parker, who, like her cousin Gerritt Smith, was a member of the Secret Six, a group of men who financed John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry in an effort to spark an armed slave rebellion.

[175] In the Declaration of Sentiments written for the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, Stanton listed a series of grievances against males who, among other things, excluded women from the ministry and other leading roles in religion.

[178] Stanton was uneasy about the belief held by many of these activists that government should enforce Christian ethics through such actions as teaching the Bible in public schools and strengthening Sunday closing laws.

What Stanton did that was new was to scrutinize the Bible from a woman's point of view, basing her findings on the proposition that much of its text reflected not the word of God but prejudice against women during a less civilized age.

"[185] In the book's closing words, Stanton expressed the hope for reconstructing "a more rational religion for the nineteenth century, and thus escape all the perplexities of the Jewish mythology as of no more importance than those of the Greek, Persian, and Egyptian.

"[186] At the 1896 NAWSA convention, Rachel Foster Avery, a rising young leader, harshly attacked The Woman's Bible, calling it a "volume with a pretentious title … without either scholarship or literary merit.

[192] In a letter to the 1902 NAWSA convention, Stanton continued her campaign, calling for "a constitutional amendment requiring an educational qualification" and saying that "everyone who votes should read and write the English language intelligently.

[198] Stanton died in New York City on October 26, 1902, 18 years before women achieved the right to vote in the United States via the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

[199] Stanton had signed a document two years earlier directing that her brain was to be donated to Cornell University for scientific study after her death, but her wishes in that regard were not carried out.

[219] The U.S. Treasury Department announced in 2016 that an image of Stanton would appear on the back of a newly designed $10 bill along with Lucretia Mott, Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, Alice Paul and the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession.