Seneca Falls Convention

Stanton and the Quaker women presented two prepared documents, the Declaration of Sentiments and an accompanying list of resolutions, to be debated and modified before being put forward for signatures.

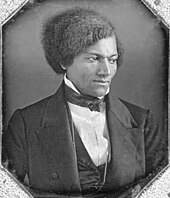

A heated debate sprang up regarding women's right to vote, with many – including Mott – urging the removal of this concept, but Frederick Douglass, who was the convention's sole African American attendee, argued eloquently for its inclusion, and the suffrage resolution was retained.

The Grimké sisters published their views against slavery in the late 1830s, and they began speaking to mixed gatherings of men and women for Garrison's American Anti-Slavery Society, as did Abby Kelley.

Mott and Stanton became friends in London and on the return voyage and together planned to organize their own convention to further the cause of women's rights, separate from abolition concerns.

In 1842 Thomas M'Clintock and his wife Mary Ann became founding members of the Western New York Anti-Slavery Society and helped write its constitution.

When he moved to Rochester in 1847, Frederick Douglass joined Amy and Isaac Post and the M'Clintocks in this Rochester-based chapter of the American Anti-Slavery Society.

[10] In 1839 in Boston, Margaret Fuller began hosting conversations, akin to French salons, among women interested in discussing the "great questions" facing their sex.

[13] State statutes and common law prohibited women from inheriting property, signing contracts, serving on juries and voting in elections.

She wrote to her friend Elizabeth J. Neal that she moved both the audience and herself to tears, saying "I infused into my speech a Homeopathic dose of woman's rights, as I take good care to do in many private conversations.

[22] The General Assembly in Pennsylvania passed a similar married woman's property law a few weeks after New York, one which Lucretia Mott and others had championed.

[23] At the National Liberty Convention, held June 14–15 in Buffalo, New York, Smith gave a major address,[24] including in his speech a demand for "universal suffrage in its broadest sense, females as well as males being entitled to vote.

"[23] The delegates approved a passage in their party platform addressing votes for women: "Neither here, nor in any other part of the world, is the right of suffrage allowed to extend beyond one of the sexes.

"[23] At this convention, five votes were placed calling for Lucretia Mott to be Smith's vice-president—the first time in the United States that a woman was suggested for federal executive office.

Over tea, Stanton, the only non-Quaker present, vented a lifetime's worth of pent-up frustration, her "long-accumulating discontent"[28] about women's subservient place in society.

Built by a congregation of abolitionists and financed in part by Richard Hunt,[13] the chapel had been the scene of many reform lectures, and was considered the only large building in the area that would open its doors to a women's rights convention.

[38] Starting at 11 o'clock, Elizabeth Cady Stanton spoke first, exhorting each woman in the audience to accept responsibility for her own life, and to "understand the height, the depth, the length, and the breadth of her own degradation.

[43] The editor of the National Reformer, a paper in Auburn, New York, reported that Mott's extemporaneous evening speech was "one of the most eloquent, logical, and philosophical discourses which we ever listened to.

[43] Further discussion of the Declaration ensued, including comments by Frederick Douglass, Thomas and Mary Ann M'Clintock, and Amy Post; the document was adopted unanimously.

[50] The National Reformer reported that those in the audience who evidently regarded the Declaration as "too bold and ultra", including the lawyers known to be opposed to the equal rights of women, "failed to call out any opposition, except in a neighboring BAR-ROOM.

"[46] Following Stanton, Thomas M'Clintock read several passages from Sir William Blackstone's laws, to expose for the audience the basis of woman's current legal condition of servitude to man.

In Massachusetts, the Lowell Courier published its opinion that, with women's equality, "the lords must wash the dishes, scour up, be put to the tub, handle the broom, darn stockings.

"[21] Horace Greeley in the New York Tribune wrote "When a sincere republican is asked to say in sober earnest what adequate reason he can give, for refusing the demand of women to an equal participation with men in political rights, he must answer, None at all.

"[21] Some of the ministers heading congregations in the area attended the Seneca Falls Convention, but none spoke out during the sessions, not even when comments from the floor were invited.

[62] The Women's Rights National Historical Park was established in 1980, and covers a total of 6.83 acres (27,600 m2) of land in Seneca Falls and nearby Waterloo, New York, USA.

"[68] In 1876, in the spirit of the nation's centennial celebrations, Stanton and Susan B. Anthony decided to write a more expansive history of the women's rights movement.

Stanton and Anthony wrote without her and, in 1881, they published the first volume of the History of Woman Suffrage, and placed themselves at each of its most important events, marginalizing Stone's contribution.

In the early 1870s, Stanton and Anthony began to present Seneca Falls as the beginning of the women's rights movement, an origin story that downplayed Stone's role.

[28] In keeping with Stanton's promotion of the table as an iconic relic, women's rights activists put it in a place of honor at the head of the casket at the funeral of Susan B. Anthony on March 14, 1906.

[34] The table is kept at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.[73] Lucretia Mott reflected in August 1848 upon the two women's rights conventions in which she had participated that summer, and assessed them no greater than other projects and missions she was involved with.

She wrote that the two gatherings were "greatly encouraging; and give hope that this long neglected subject will soon begin to receive the attention that its importance demands.