Elizabeth Garrett Anderson

Newson's malting business expanded and more children were born, Edmund (1840), Alice (1842), Agnes (1845),[9] Millicent (1847), who was to become a leader in the constitutional campaign for women's suffrage, Sam (1850), Josephine (1853) and George (1854).

Elizabeth was encouraged to take an interest in local politics and, contrary to practices at the time, was allowed the freedom to explore the town with its nearby salt-marshes, beach and the small port of Slaughden with its boatbuilders' yards and sailmakers' lofts.

Mornings were spent in the schoolroom; there were regimented afternoon walks; educating the young ladies continued at mealtimes when Edgeworth ate with the family; at night, the governess slept in a curtained off area in the girls' bedroom.

[4] After this formal education, Garrett spent the next nine years tending to domestic duties, but she continued to study Latin and arithmetic in the mornings and also read widely.

Her sister Millicent recalled Garrett's weekly lectures, "Talks on Things in General", when her younger siblings would gather while she discussed politics and current affairs from Garibaldi to Macaulay's History of England.

[16] In 1854, when she was eighteen, Garrett and her sister went on a long visit to their school friends, Jane and Anne Crow, in Gateshead where she met Emily Davies, the early feminist and future co-founder of Girton College, Cambridge.

It may have been in the English Woman's Journal, first issued in 1858, that Garrett first read of Elizabeth Blackwell, who had become the first female doctor in the United States in 1849.

[19] After an initial unsuccessful visit to leading doctors in Harley Street, Garrett decided to first spend six months as a surgery nurse at Middlesex Hospital, London in August 1860.

Garrett then applied to several medical schools, including Oxford, Cambridge, Glasgow, Edinburgh, St Andrews and the Royal College of Surgeons, all of which refused her admittance.

While both are considered "outstanding" medical figures of the late 19th century, Garrett was able to obtain her credentials by way of a "side door" through a loophole in admissions at the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries.

[23] Having privately obtained a certificate in anatomy and physiology, she was admitted in 1862 by the Society of Apothecaries who, as a condition of their charter, could not legally exclude her on account of her sex.

[24] She continued her battle to qualify by studying privately with various professors, including some at the University of St Andrews, the Edinburgh Royal Maternity and the London Hospital Medical School.

[25] In 1865, Garrett finally took her exam and obtained a licence (LSA) from the Society of Apothecaries to practise medicine, the first woman qualified in Britain to do so openly (previously there was Dr James Barry who was born and raised female but presented as male from the age of 20).

After six months in practice, she wished to open an outpatients dispensary, to enable poor women to obtain medical help from a qualified practitioner of their own gender.

In 1865, there was an outbreak of cholera in Britain, affecting both rich and poor, and in their panic, some people forgot any prejudices they had in relation to a female physician.

The first death due to cholera occurred in 1866, but by then Garrett had already opened St Mary's Dispensary for Women and Children, at 69 Seymour Place.

[4][34] The same year she was elected to the first London School Board, an office newly opened to women; Garrett's was the highest vote among all the candidates.

Also in that year, she was made a visiting physician of the East London Hospital for Children (later the Queen Elizabeth Hospital for Children), becoming the first woman in Britain to be appointed to a medical post,[35] but she found the duties of these two positions to be incompatible with her principal work in her private practice and the dispensary, as well as her role as a new mother, so she resigned from these posts by 1873.

[38] Garrett's counter-argument was that the real danger for women was not education but boredom and that fresh air and exercise were preferable to sitting by the fire with a novel.

[42] This was "one of several instances where Garrett, uniquely, was able to enter a hitherto all male medical institution which subsequently moved formally to exclude any women who might seek to follow her.

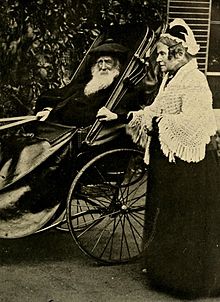

[4] She enjoyed a happy marriage and in later life, devoted time to Alde House, gardening, and travelling with younger members of the extended family.

The former Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital buildings are incorporated into the new National Headquarters for the public service trade union UNISON.

The new medical school at the University of Worcester, due to accept its first students in 2023, is to be called the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Building.