Quadric

In three-dimensional space, quadrics include ellipsoids, paraboloids, and hyperboloids.

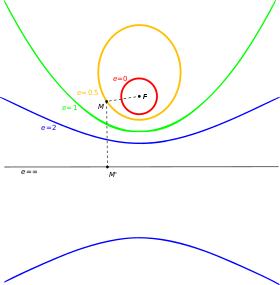

More generally, a quadric hypersurface (of dimension D) embedded in a higher dimensional space (of dimension D + 1) is defined as the zero set of an irreducible polynomial of degree two in D + 1 variables; for example, D=1 is the case of conic sections (plane curves).

The quadric surfaces are classified and named by their shape, which corresponds to the orbits under affine transformations.

That is, if an affine transformation maps a quadric onto another one, they belong to the same class, and share the same name and many properties.

Each of these 17 normal forms[2] corresponds to a single orbit under affine transformations.

(pair of complex conjugate parallel planes, a reducible quadric).

When two or more of the parameters of the canonical equation are equal, one obtains a quadric of revolution, which remains invariant when rotated around an axis (or infinitely many axes, in the case of the sphere).

An affine quadric is the set of zeros of a polynomial of degree two.

When not specified otherwise, the polynomial is supposed to have real coefficients, and the zeros are points in a Euclidean space.

As usual in algebraic geometry, it is often useful to consider points over an algebraically closed field containing the polynomial coefficients, generally the complex numbers, when the coefficients are real.

As the above process of homogenization can be reverted by setting X0 = 1: it is often useful to not distinguish an affine quadric from its projective completion, and to talk of the affine equation or the projective equation of a quadric.

A quadric in an affine space of dimension n is the set of zeros of a polynomial of degree 2.

That is, it is the set of the points whose coordinates satisfy an equation where the polynomial p has the form for a matrix

A non-degenerate quadric is non-singular in the sense that its projective completion has no singular point (a cylinder is non-singular in the affine space, but it is a degenerate quadric that has a singular point at infinity).

The second case generates the ellipsoid, the elliptic paraboloid or the hyperboloid of two sheets, depending on whether the chosen plane at infinity cuts the quadric in the empty set, in a point, or in a nondegenerate conic respectively.

The third case generates the hyperbolic paraboloid or the hyperboloid of one sheet, depending on whether the plane at infinity cuts it in two lines, or in a nondegenerate conic respectively.

We see that projective transformations don't mix Gaussian curvatures of different sign.

Expressing the points of the quadric in terms of the direction of the corresponding line provides parametric equations of the following forms.

In the case of conic sections (quadric curves), this parametrization establishes a bijection between a projective conic section and a projective line; this bijection is an isomorphism of algebraic curves.

In higher dimensions, the parametrization defines a birational map, which is a bijection between dense open subsets of the quadric and a projective space of the same dimension (the topology that is considered is the usual one in the case of a real or complex quadric, or the Zariski topology in all cases).

For computing the parametrization and proving that the degrees are as asserted, one may proceed as follows in the affine case.

of the preceding section becomes By expanding the squares, simplifying the constant terms, dividing by

and simplifying the expression of the last coordinate, one obtains the parametric equation By homogenizing, one obtains the projective parametrization A straightforward verification shows that this induces a bijection between the points of the quadric such that

In this specific case, these points have nonreal complex coordinates, but it suffices to change one sign in the equation of the quadric for producing real points that are not obtained with the resulting parametrization.

of the rational numbers, one can suppose that the coefficients are integers by clearing denominators.

Finding the rational points of a projective quadric amounts thus to solving a Diophantine equation.

(The names of variables and parameters are being changed from the above ones to those that are common when considering Pythagorean triples).

In order to omit dealing with coordinates, a projective quadric is usually defined by starting with a quadratic form on a vector space.

In this case the f-radical is the common point of all tangents, the so called knot.

Examples: It is not reasonable to formally extend the definition of quadrics to spaces over genuine skew fields (division rings).