Projective space

In mathematics, the concept of a projective space originated from the visual effect of perspective, where parallel lines seem to meet at infinity.

This definition of a projective space has the disadvantage of not being isotropic, having two different sorts of points, which must be considered separately in proofs.

For some such set of axioms, the projective spaces that are defined have been shown to be equivalent to those resulting from the following definition, which is more often encountered in modern textbooks.

Such statements are suggested by the study of perspective, which may be considered as a central projection of the three dimensional space onto a plane (see Pinhole camera model).

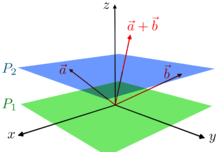

Such an intersection exists if and only if the point P does not belong to the plane (P1, in green on the figure) that passes through O and is parallel to P2.

All these definitions extend naturally to the case where K is a division ring; see, for example, Quaternionic projective space.

By rescaling the first n vectors, any frame can be rewritten as (p(e′0), ..., p(e′n+1)) such that e′n+1 = e′0 + ... + e′n; this representation is unique up to the multiplication of all e′i with a common nonzero factor.

Unlike in Euclidean geometry, the concept of an angle does not apply in projective geometry, because no measure of angles is invariant with respect to projective transformations, as is seen in perspective drawing from a changing perspective.

Again this notion has an intuitive basis, such as railway tracks meeting at the horizon in a perspective drawing.

Several major types of more abstract mathematics (including invariant theory, the Italian school of algebraic geometry, and Felix Klein's Erlangen programme resulting in the study of the classical groups) were motivated by projective geometry.

Historically, homographies (and projective spaces) have been introduced to study perspective and projections in Euclidean geometry, and the term homography, which, etymologically, roughly means "similar drawing", dates from this time.

A projective space may be constructed as the set of the lines of a vector space over a given field (the above definition is based on this version); this construction facilitates the definition of projective coordinates and allows using the tools of linear algebra for the study of homographies.

In both lines, the intersection of the two charts is the set of nonzero real numbers, and the transition map is

Originally, algebraic geometry was the study of common zeros of sets of multivariate polynomials.

These common zeros, called algebraic varieties belong to an affine space.

It appeared soon, that in the case of real coefficients, one must consider all the complex zeros for having accurate results.

For example, the fundamental theorem of algebra asserts that a univariate square-free polynomial of degree n has exactly n complex roots.

[c] Any affine variety can be completed, in a unique way, into a projective variety by adding its points at infinity, which consists of homogenizing the defining polynomials, and removing the components that are contained in the hyperplane at infinity, by saturating with respect to the homogenizing variable.

This is a generalization to every ground field of the compactness of the real and complex projective space.

The structures defined by these axioms are more general than those obtained from the vector space construction given above.

However, for dimension two, there are examples that satisfy these axioms that can not be constructed from vector spaces (or even modules over division rings).

In dimension one, any set with at least three elements satisfies the axioms, so it is usual to assume additional structure for projective lines defined axiomatically.

[5] It is possible to avoid the troublesome cases in low dimensions by adding or modifying axioms that define a projective space.

[6] To ensure that the dimension is at least two, replace the three point per line axiom above by: To avoid the non-Desarguesian planes, include Pappus's theorem as an axiom;[e] And, to ensure that the vector space is defined over a field that does not have even characteristic include Fano's axiom;[f] A subspace of the projective space is a subset X, such that any line containing two points of X is a subset of X (that is, completely contained in X).

The geometric dimension of the space is said to be n if that is the largest number for which there is a strictly ascending chain of subspaces of this form:

Projective spaces admit an equivalent formulation in terms of lattice theory.

For finite projective spaces of dimension at least three, Wedderburn's theorem implies that the division ring over which the projective space is defined must be a finite field, GF(q), whose order (that is, number of elements) is q (a prime power).

The numbers beyond this are very difficult to calculate and are not determined except for some zero values due to the Bruck–Ryser theorem.

Thus if one identifies the scalar multiples of the identity map with the underlying field K, the set of K-linear morphisms from P(V) to P(W) is simply P(L(V, W)).

One would like to be able to associate a projective space to every quasi-coherent sheaf E over a scheme Y, not just the locally free ones.