Elliptic operator

In the theory of partial differential equations, elliptic operators are differential operators that generalize the Laplace operator.

They are defined by the condition that the coefficients of the highest-order derivatives be positive, which implies the key property that the principal symbol is invertible, or equivalently that there are no real characteristic directions.

Elliptic operators are typical of potential theory, and they appear frequently in electrostatics and continuum mechanics.

Elliptic regularity implies that their solutions tend to be smooth functions (if the coefficients in the operator are smooth).

Steady-state solutions to hyperbolic and parabolic equations generally solve elliptic equations.

be a linear differential operator of order m on a domain

denotes the partial derivative of order

In many applications, this condition is not strong enough, and instead a uniform ellipticity condition may be imposed for operators of order m = 2k:

Note that ellipticity only depends on the highest-order terms.

is elliptic if its linearization is; i.e. the first-order Taylor expansion with respect to u and its derivatives about any point is an elliptic operator.

Let L be an elliptic operator of order 2k with coefficients having 2k continuous derivatives.

The Dirichlet problem for L is to find a function u, given a function f and some appropriate boundary values, such that Lu = f and such that u has the appropriate boundary values and normal derivatives.

The existence theory for elliptic operators, using Gårding's inequality, Lax–Milgram lemma and Fredholm alternative, states the sufficient condition for a weak solution u to exist in the Sobolev space Hk.

For example, for a Second-order Elliptic operator as in Example 2, This situation is ultimately unsatisfactory, as the weak solution u might not have enough derivatives for the expression Lu to be well-defined in the classical sense.

The elliptic regularity theorem guarantees that, provided f is square-integrable, u will in fact have 2k square-integrable weak derivatives.

The property also means that every fundamental solution of an elliptic operator is infinitely differentiable in any neighborhood not containing 0.

As an application, suppose a function

Since the Cauchy-Riemann equations form an elliptic operator, it follows that

satisfies the assumptions of Lax–Milgram lemma.

be a (possibly nonlinear) differential operator between vector bundles of any rank.

(Basically, what we are doing is replacing the highest order covariant derivatives

is a linear isomorphism for every non-zero

is (uniformly) strongly elliptic if for some constant

are covector fields or one-forms, but the

are elements of the vector bundle upon which

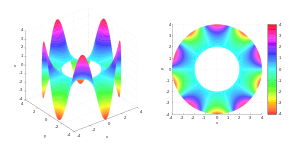

The quintessential example of a (strongly) elliptic operator is the Laplacian (or its negative, depending upon convention).

needs to be of even order for strong ellipticity to even be an option.

On the other hand, a weakly elliptic first-order operator, such as the Dirac operator can square to become a strongly elliptic operator, such as the Laplacian.

Weak ellipticity is nevertheless strong enough for the Fredholm alternative, Schauder estimates, and the Atiyah–Singer index theorem.

On the other hand, we need strong ellipticity for the maximum principle, and to guarantee that the eigenvalues are discrete, and their only limit point is infinity.