Embanking of the tidal Thames

Today, over 200 miles of walls line the river's banks from Teddington down to its mouth in the North Sea; they defend a tidal flood plain where 1.25 million people work and live.

Since the Thames has a large tidal amplitude, early modern thinkers could not believe local people were capable of building mighty embankments beside it; hence the works were attributed to "the Romans".

[7] Hilda Ormsby—one of the first to write a modern geographical textbook on London—visualised the scene:In our mental picture of "London before the Houses", we must conceive of the Flood Plain as a flat extent of peaty, water-logged land, raised a foot or two above high water, covered with a coarse, rank herbage and intersected by innumerable little winding creeks, filled with water only at high tide...... the river must have been both wider and shallower before embanking took place.

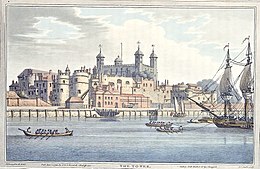

The tidal Thames today is virtually a canal[14][2]—in central London, about 250 metres wide—flowing between solid artificial walls, and laterally restrained by these at high tide.

[15] For instance, the Victorian engineer James Walker reported that, if the walls were removedthe Thames would, at the very next tide, take possession of the large space that had been so long abstracted from it, and would be generally five times its present width.

[28] The scientist and architect Sir Christopher Wren thought the walls were built to restrain wind-blown sand dunes, and attributed them to the Romans, for similar reasons.

[29] The influential Victorian engineer James Walker—who was himself to lay down the lines of the Thames Embankment in central London[30]—thought the same, addingThat they are the result of skill and bold enterprise, not unworthy of any period, is certain.

Spurrell had visited the excavations for the Royal Albert Dock, the Port of Tilbury and Crossness Pumping Station, and in each place he saw—7 to 9 feet below the surface—traces of human habitation, including Roman-era pottery.

Spurrell thought the mud layers ("tidal clay")[13] must have formed when the spring tides deposited sediment (a process still observable in his day at certain river margins, called Saltings).

[51] John H. Evans writing before the 1953 floods and using data from boreholes and similar sources found that Roman-era human occupation sites were well above the high water levels of the era, hence needed no defensive embankments.

Later improvements have included facings of Kentish ragstone,[74] tightly packed granite or sandstone[75] to reduce erosion from navigational wash; the use of chalk instead of clay; protecting the walls with interlocking concrete blocks; and the use of gently sloping profiles to increase stability and absorb wave energy.

Explained Flaxman Spurell: Many writers are impressed with the "mighty", "stupendous", or "vast" embankments which keep out the water of the river, while Dugdale and Wren seem to have thought that because they were so great, none but Romans could have raised them.

[91] Later, the dissolution of the monasteries may have caused loss of local expertise with consequent wall breaches that were not repaired for decades e.g. at Lesnes Abbey (Plumstead and Erith).

In 1658 it was complained that a shoemaker called Jenkin Ellis, who owned just 10 yards of river front, had turned it to account by selling permission to anchor ships ten abreast.

"As long ago as 1848", wrote Martin Bates, "Sir William Tite had deduced that nearly all the land south of Thames Street in the City of London 'had been gained from the river by a series of strong embankments'."

[111] Wrote John Ehrman: One observer reckoned that between London Bridge and Gravesend the wharves and warehouses, with their piers and steps, were covering 300 to 400 feet of new ground during each year of James II's reign... As the waterfront was built over, so the river silted up off the new walls and landing stages, and by 1687 the Navy Board estimated the channel of the Thames had been narrowed by one-fifth by the "new encroachments".

[133][134] ) An example is Geoffrey Chaucer, who in 1390 was appointed to a commission sent to survey the walls between Greenwich and Woolwich, and compel landowners to repair them, "showing no favour to rich or poor".

Each extension was usually achieved by the erection of a timber revetment upon the foreshore, behind which was dumped an assortment of domestic or other waste, sealed by the surfaces of the yards or buildings laid out over the newly-won land.

[178] Already in 1598, Elizabethan historian John Stow could write: ... from this Precinct of Saint Kathren, to Wapping in the Wose, and Wapping it selfe, (the vsuall place of Execution for the hanging of Pyrates and sea Rouers, at the lowe water marke, and there to remaine, till thrée Tydes had ouerflowed them) and neuer a house standing within these fortie yeares, but is now made a continuall stréete, or ra∣ther a filthy straight [open] passage, with Lanes and Allyes, of small Tenements inhabited by Saylors, and Uictuallers, along by the Riuer of Thames, almost to Radliffe, a good myle from the Tower.

[183] The result was described by Robin Pearson in Insuring the Industrial Revolution: Dwellings, workshops and warehouses were thrown up rapidly, with little regard to the quality or materials of construction or the goods and manufacturing processes they contained.

They were squeezed between wharves, rope walks, tar and pitch boilers, sail cloth and turpentine factories, timber yards, cooperages and small docks along the lanes and alleys of St Katherine's, Wapping, Shadwell, Ratcliffe and Limehouse ...

[193][191] On 25 March 1448, owing to the fault of one "John Harpour, gentleman", who did not repair his bank opposite to Deptford Strond, the violence of tides made a 100-yard[194] breach, drowning 1,000 acres of land.

A classic fate of geological formations like the Isle of Dogs is meander cutoff, when the river takes a short-cut across the neck of land; the old bend is left as an oxbow lake.

Samuel Pepys' diary for 23 March 1660 recorded: [In the Isle of Dogs] we saw the great breach which the late high water had made, to the loss of many thousand pounds to the people about Limehouse.

[211] Successive tides continued to pour back and forth, widening the gap, gathering strength, cutting a channel through the clay and getting down to the sand and gravel strata, at which the scouring became so rapid the rush was overwhelming.

[218] He adopted two simultaneous principles: Beset with difficulties, including suppliers who sold him defective clay, a nightwatchman who failed to warn him about an extra-high tide, strikes, and cashflow problems, Perry eventually succeeded, finally plugging the gap on 18 June 1719.

[225] "That noe House Outhouse or other building whatsoever (Cranes and Sheds for present use onely excepted) shall be built or erected within the distance of Forty foote of such part of any Wall Key or Wharfe as bounds the River of Thames, from Tower Wharfe to London Bridge and from London Bridge to the Temple Staires, Nor any House Outhouse or other building (Cranes onely excepted) be built or erected within the distance of threescore and ten foote of the midle of any part of the Coommon Sewers coommonly called or knowne by the nams of Bridewell Docke Fleete Ditch and Turmill Brooke from the River of Thames to Clarkenwell upon either side of them before the fower and twentieth day of March which shall be in the yeare of our Lord One thousand six hundred sixty eight".

[227] In 1770, at a site that is today between the Strand and Victoria Embankment Gardens, but then was under the waters of the Thames, the Adam brothers laid a foundation that protruded 100 feet into the stream.

[225] In 1817 an act of Parliament (see box) authorised a road to be made along the bank from Westminster to the newly erected Millbank Penitentiary, going through land of the Earl Grosvenor.

A sanitary crisis and the urgent need to build a strategic low-level sewer somewhere along the north bank of the Thames—the only alternative was the congested Strand—stimulated the decision to authorise the first of these, the Victoria Embankment.