Empty tomb

Matthew introduces guards and a doublet where the women are told twice, by angels and then by Jesus, that he will meet the disciples in Galilee.

[12] Luke changes Mark's one "young man [...] dressed in a white robe" to two, adds Peter's inspection of the tomb,[13] and deletes the promise that Jesus would meet his disciples in Galilee.

[14] John reduces the women to the solitary Mary Magdalene, and introduces the "beloved disciple" who visits the empty tomb with Peter and is the first to understand its significance.

[17] It concludes with the women fleeing from the empty tomb and telling no one what they have seen, and the general scholarly view is that this was the original ending of this gospel, with the remaining verses, Mark 16:9–16, being added later.

[22] The introduction of the guard is apparently aimed at countering stories that Jesus' body had been stolen by his disciples, thus eliminating any explanation of the empty tomb other than that offered by the angel, that he has been raised.

[14] In Mark and Matthew, Jesus tells the disciples to meet him there, but in Luke the post-resurrection appearances are only in Jerusalem.

[23] Mark and Luke report that the women visited the tomb in order to finish anointing the body of Jesus.

The story ends with Peter visiting the tomb and seeing the burial cloths, but instead of believing in the resurrection he remains perplexed.

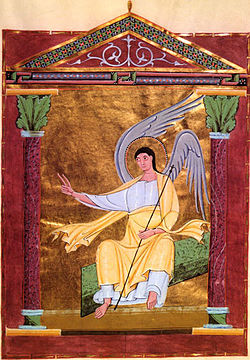

There was a violent earthquake, for an angel of the Lord came down from heaven and, going to the tomb, rolled back the stone and sat on it.

Remember how he told you, while he was still with you in Galilee: 'The Son of Man must be delivered over to the hands of sinners, be crucified and on the third day be raised again.'

John's chapter 20 can be divided into three scenes: (1) the discovery of the empty tomb, verses 1–10; (2) appearance of Jesus to Mary Magdalene, 11–18; and (3) appearances to the disciples, especially Thomas, verses 19–29; the last is not part of the "empty tomb" episode and is not included in the following table.

[16] Early on the first day of the week, while it was still dark, Mary Magdalene went to the tomb and saw that the stone had been removed from the entrance.

As she wept, she bent over to look into the tomb and saw two angels in white, seated where Jesus' body had been, one at the head and the other at the foot.

So she came running to Simon Peter and the other disciple, the one Jesus loved, and said, "They have taken the Lord out of the tomb, and we don't know where they have put him!"

Although Jews, Greeks, and Romans all believed in the reality of resurrection, they differed in their respective conceptions and interpretations of it.

[31][32][33] Christians certainly knew of numerous resurrection-events allegedly experienced by persons other than Jesus: the early 3rd-century Christian theologian Origen, for example, did not deny the resurrection of the 7th-century BCE semi-legendary Greek poet Aristeas or the immortality of the 2nd-century CE Greek youth Antinous, the beloved of the Roman Emperor Hadrian, but said the first had been the work of demons, not God, while the second, unlike Jesus, was unworthy of worship.

As such, Mark narrates that the women had seen the spot where Jesus was laid while the later gospels state that the tomb was "new" and unused.

[41] Richard C. Miller compares the ending of Mark to Hellenistic and Roman translation stories of heroes which involve missing bodies.

[44] Other suggestions, not supported in mainstream scholarship, are that Jesus had not really died on the cross, or was lost due to natural causes.

[45] The absence of any reference to the story of Jesus' empty tomb in the Pauline epistles and the Easter kerygma (preaching or proclamation) of the earliest church, originating perhaps in the Christian community of Antioch in the 30s and preserved in 1 Corinthians,[46] has led some scholars to suggest that Mark invented it.

[47] Other scholars have argued that instead, Paul presupposes the empty tomb, specifically in the early creed passed down in 1 Cor.

Smith believes that Mark has adapted two separate traditions of resurrection and disappearance into one Easter narrative.

"[citation needed] N. T. Wright emphatically and extensively argues for the reality of the empty tomb and the subsequent appearances of Jesus, reasoning that as a matter of "inference"[53] both a bodily resurrection and later bodily appearances of Jesus are far better explanations for the empty tomb and the 'meetings' and the rise of Christianity than are any other theories, including those of Ehrman.

[53][54] Dale Allison has argued for an empty tomb, that was later followed by visions of Jesus by the Apostles and Mary Magdalene, while also accepting the historicity of the resurrection.

[55] Christian biblical scholars have used textual critical methods to support the historicity of the tradition that "Mary of Magdala had indeed been the first to see Jesus," most notably the Criterion of Embarrassment in recent years.

[56][57] According to Dale Allison, the inclusion of women as the first witnesses to the risen Jesus "once suspect, confirms the truth of the story.

"[58] According to Géza Vermes, the empty tomb developed independently from the post-resurrection appearances, as they are never directly coordinated to form a combined argument.