Energy efficiency in British housing

Domestic housing in the United Kingdom presents a possible opportunity for achieving the 20% overall cut in UK greenhouse gas emissions targeted by the Government for 2010.

However, the process of achieving that drop is proving problematic given the very wide range of age and condition of the UK housing stock.

[1] A 2006 report commissioned by British Gas[3] estimated the average carbon emissions for housing in each of the local authorities in Great Britain, the first time that this had been done.

[5] Whilst some organisations applauded the initial announcement of the scheme, in the pre-budget statement from the then UK Chancellor, Gordon Brown, others are concerned about the government's ability to deliver on the promise.

[8] In 2004, housing (including space heating, hot water, lighting, cooking, and appliances) accounted for 30.23% of all energy use in the UK (up from 27.70% in 1990).

This thermal performance was expressed in the imperial units of the time (the amount of heat in BTU lost per square foot, for each degree Fahrenheit of temperature difference between inside and outside).

Part F of the 1965 regulations defines minimum thermal performance, and schedule 11 of the same document gives examples of compliant methods for builders and architects to refer to.

The 1972 regulations [16] retained the same standards but converted to metric units (mm) and the modern u-value (the amount of heat lost per square metre, for each degree Celsius of temperature difference between inside and outside).

The changes were the first to the regulations brought about by the desire to reduce emissions, though some have raised doubts about whether they will actually achieve the 20% cut (see criticisms section).

[25][26] In December 2006, the government announced their ambition that all new housing should be built to zero-carbon standards from 2016;[27] i.e., that the carbon emitted during a typical year should be balanced by renewable energy generation.

Despite being the first country in the world to adopt such a policy[28] the initiative was generally welcomed by the industry in principle,[29] despite some subsequent concern over the practicalities.

The UK Green Building Council estimated that the change, published at the time of the March 2011 budget, will result in only two-thirds of the emissions of a new home being mitigated.

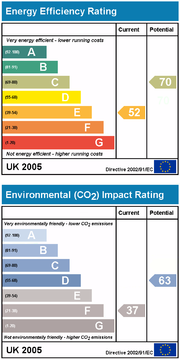

[39] The scheme provides the owner or landlord with an 'energy label' so that they can demonstrate the energy efficiency of the property, and is also included in the new Home Information Packs.

For example, it ignores thick walls with their low heat transmission, and its recommendations for compact fluorescent lamps, which can damage sensitive textiles and paintings.

This is not a well known type of house, but it has a range of positive advantages like it is built out of renewable resources and it is a breathable structure thus making it much healthier to live in.

[45] A similar scheme, the Scottish Community and Household Renewables Initiative operates in Scotland, which also offers grants towards the cost of air source heat pumps.

[46] In the South,[citation needed] most local authority housing was sold off in the 1980s-90s under RTB (Right to buy scheme), so the remaining stock is small.

Energy World was preceded by the earlier Salford low-energy houses, built in the early 1980s, which continue to be 40% more efficient than the 2010 Building Regulations.

In use, BedZED has yielded considerable useful feedback, not least that energy efficiency and passive design features delivery more reliable reduced carbon emissions than active systems.

Measured electrical use for cooking, appliances and occupant's plug loads ('unregulated energy' consumption) are some 55% lower than UK norms (bedzed-seven-years-on).

[48] The Green Building in Manchester City Centre and has been built to high energy efficiency standards and won a 2006 Civic Trust Award for its sustainable design.

[49] The cylindrical shape of the ten-storey tower provides the smallest surface area related to the volume, ensuring less energy is lost through thermal dissipation.

The South Yorkshire Energy Centre at Heeley City Farm in Sheffield is an example of refurbishing an existing property to show the options available.

A survey by Liverpool John Moores University predicted that the actual figure would be 6% (Johnson, JA "Building Regulations Research Project").

Several commercial energy modeling software packages have now also been verified as producing acceptable evidence by the BRE Global & UK Government.