English language in Europe

Outside of these states, it has official status in Malta, the Crown Dependencies (the Isle of Man, Jersey and Guernsey), Gibraltar and the Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia (two of the British Overseas Territories).

In the Netherlands, English has an official status as a regional language on the isles of Saba and Sint Eustatius (located in the Caribbean).

In other parts of Europe, English is spoken mainly by those who have learnt it as a second language, but also, to a lesser extent, natively by some expatriates from some countries in the English-speaking world.

[2] European English is known by a number of colloquial portmanteau words, including: Eurolish (first recorded in 1979), Eurish (1993) and Eurlish (2006).

The Chronicle documents the subsequent influx of settlers who eventually established seven kingdoms: Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Kent, Essex, Sussex and Wessex.

After Scots and Frisian, the next closest relative is the modern Low German language of the eastern Netherlands and northern Germany, which was the old homeland of the Anglo-Saxon invaders of Britain.

With the arrival of the Normans in Ireland in 1169, King Henry II of England gained Irish lands and the fealty of many native Gaelic nobles.

Irish appears on government forms, euro-currency, and postage stamps, in traditional music and in media promoting folk culture.

But with these important exceptions, and despite the presence of Irish loan words in Hiberno-English, Ireland is today largely an English-speaking country.

However, in the 2000s a Gaeltacht Quarter was established in Belfast to drive inward investment as a response to a notable level of public interest in learning Irish and the expansion of Irish-medium education (predominantly attended by children whose home language is English) since the 1970s.

Ability varies; 64,847 people stated they could understand, speak, read and write Irish in the 2011 UK census, the majority of whom have learnt it as a second language.

Otherwise, except for place names and folk music, English is effectively the sole language of Northern Ireland.

Anglic speakers were actually established in Lothian by the 7th century,[citation needed] but remained confined there, and indeed contracted slightly to the advance of the Gaelic language.

Although the military aristocracy employed French and Gaelic, these small urban communities appear to have been using English as something more than a lingua franca by the end of the 13th century.

As a consequence of the outcome of the Wars of Independence though, the English of Lothian who lived under the King of Scots had to accept Scottish identity.

The introduction of King James Version of the Bible into Scottish churches also was a blow to the Scots language, since it used Southern English forms.

Approximately 2% of the population use Scottish Gaelic as their language of everyday use, primarily in the northern and western regions of the country.

Edward followed the practice used by his Norman predecessors in their subjugation of the English, and constructed a series of great stone castles in order to control Wales, thus preventing further military action against England by the Welsh.

Besides English, some (very few) inhabitants of these islands speak regional languages[citation needed], or those related to French (such as Jèrriais, Dgèrnésiais and Sercquiais).

Most of Cyprus gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1960, with the UK, Greece and Turkey retaining limited rights to intervene in internal affairs.

Since the effective partition of the island in 1974, Greek and Turkish Cypriots have had little opportunity or inclination to learn the others' language, and are more likely to talk to each other in English.

Overall though, the French policy was indicative of a desire to distance Cyprus from the former British colonial power, against which a bitter war of independence had recently been fought and won.

The territory's Gibraltarian inhabitants have a rich cultural heritage as a result of the mix of the neighbouring Andalusian population with immigrants from Great Britain, Genoa, Malta, Portugal, Morocco and India.

Although not an official language, English tends to be used on much public signage for the benefit of tourists and expatriates, alongside Castilian Spanish and Menorcan Catalan.

There are also pockets of native English speakers to be found throughout Europe, such as in southern Spain, France, Algarve in Portugal, as well as numerous US and British military bases in Germany.

There are communities of native English speakers in some European cities outside the UK and Ireland, such as Amsterdam, Athens, Barcelona, Berlin, Brussels, Copenhagen, Helsinki, Oslo, Paris, Prague, Rome, Stockholm, and Vienna.

In Luxembourg, a trilingual country, there was a proposal in 2019 to make English an official language, but this ultimately failed to get the required minimum number of signatures to be discussed by the parliament.

He cited the difficulty typically encountered by foreigners in learning Finnish and the aim of making Helsinki more attractive to international talent.

[10] Throughout Europe, tourism, publishing, finance, computers and related industries rely heavily on English due to Anglophone trade ties.

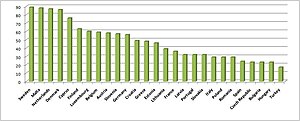

On average in 2012, 38% of citizens of the European Union (excluding the United Kingdom and Ireland) stated that they have sufficient knowledge of English to have a conversation in this language.