Engolo

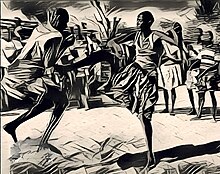

N'golo (anglicized as Engolo) is a traditional Bantu martial art and game from Angola, that combines elements of combat and dance, performed in a circle accompanied by music and singing.

[3] The combat style of engolo encompasses a variety of techniques, including different types of kicks, dodges, and takedowns, with a particular emphasis on inverted positions.

[4] Engolo was "rediscovered" in 1950s when the Angolan artist Albano Neves e Sousa included it in a collection of drawings, highlighting its similarities to the Afro-Brazilian martial art of Capoeira.

[6] Known sources document only one African combat game beside engolo that uses similar kicking techniques – moraingy on Madagascar and surrounding islands.

[7] The term ngolo derived from the Kikongo Bantu language and signifies concepts related to strength, power, and energy.

[15] Dancing in a circle holds significance, representing protection and strength, symbolizing the bond with the spirit world, life, and the divine.

In such cases, they enthusiastically leap into the circle, showcasing agile movements and occasional shouts while awaiting someone to join and engage in the play.

[3] According to Desch-Obi, engolo was likely developed by Bantu shamans and warriors in ancient Angola,[18] based on the inverted worldview of kongo religion.

Desch-Obi finds that using the zebra as a combat role model in Angola makes sense because it symbolizes nimbleness and agile defense.

[9] Matthew Zylstra suggests that a dance performed by the Gwikwe Bushmen bears a striking resemblance to the Angolan art.

He proposes a theory that the Bantu peoples in southern Angola, who interacted with San Bushmen groups in the region, may have known such dances and integrated them into their cultures.

[23]In the mid-17th century, Italian missionary Cavazzi also described the handstand technique of Angolan nganga: To augment the reputation of his excellency, he frequently walks turned upside down, with his hands on the ground and his feet in the air.

"[20]In 17th century, new military formation of kilombo, a fortified war camp surrounded by a wooden palisade, appeared among Imbangala warriors, which would soon be used in Brazil by freed Angolans.

[25] In the early 20th century, Portuguese ethnographer Augusto Bastos documented a capoeira-like combat game in the Benguela district: The Quilengues have an exercise, which they call ómudinhu.

[3] The art of engolo spread from Africa to the Americas, mainly among enslaved people taken from Angola and transported to the colonies via the Atlantic slave trade routes.

In that time, wrestling was not the dominant technique of ladja, but kicks, many of them inverted, and a significant number of hand strikes from kokoyé.

[35] Soon freed slaves started founding settlements in remote areas, calling them kilombo, meaning a war camp in the Kimbundu Bantu language.

[36] Portuguese sources mentioned that it took more than one dragoon to capture a quilombo warrior, as they defended themselves with a "strangely moving fighting technique".

As the end of the 18th century, the Angolan fighting technique in Brazil started to be called capoeira,[41] named after the clearings in the forest where freed slaves resided and practice its skills.

[42] During the 19th century, the street capoeiragem in Rio became associated with gangs and very different from the original Angolan art, including hand strikes, head butts, clubs and daggers.

In the early 20th century, Anibal Burlamaqui and Agenor Moreira Sampaio first codified the street version of capoeira as a national martial art, removing music and dance and incorporating strikes from boxing, judo and other disciplines.

Modern capoeira remains firmly based on crescent and pushing kicks (often from inverted positions), sweeps, and acrobatic evasions inherited from engolo.

[43] Professor Desch-Obi finds that the evolution from engolo to capoeira took place within a relatively isolated context, because the Portuguese lacked prevalent unarmed martial art to blend with.

The sole new form incorporated in engolo was headbutting, derived from a distinct African practice known as jogo de cabeçadas.

"[45] Also, the angolan painter Neves e Sousa, who drew engolo games in Mucope, visited Brazil in 1960s asserting that "N’golo is capoeira".

[17]Engolo players use casual terms like mussana and ngatussana for kicks and koyola for dragging or pulling, without a formalized kick-naming system seen in martial arts.

[17] Engolo's movements are rooted in the specific fundamental jumping moves, that serve as the foundation for offensive and evasive maneuvers.

[17] Engolo practitioners employ a hooking kick executed from behind, resembling the capoeira move known as gancho de costas.

[52] With this worldview, practitioners of African martial arts deliberately invert themselves upside down to emulate the ancestors, and to draw power from the ancestral realm.

[17] Painter Neves e Sousa described engolo as part of a rite of passage (efico and omuhelo), wherein young boys competed for a bride.