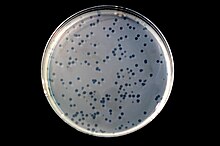

Ensifer meliloti

Because soil often contains a limited amount of nitrogen for plant use, the symbiotic relationship between S. meliloti and their legume hosts has agricultural applications.

[13] Symbiosis between S. meliloti and its legume hosts begins when the plant secretes an array of betaines and flavonoids into the rhizosphere: 4,4′-dihydroxy-2′-methoxychalcone,[14] chrysoeriol,[15] cynaroside,[15] 4′,7-dihydroxyflavone,[14] 6′′-O-malonylononin,[16] liquiritigenin,[14] luteolin,[17] 3′,5-dimethoxyluteolin,[15] 5-methoxyluteolin,[15] medicarpin,[16] stachydrine,[18] and trigonelline.

[18] These compounds attract S. meliloti to the surface of the root hairs of the plant where the bacteria begin secreting nod factors.

The bacteria develop into bacteroids within newly formed root nodules and perform nitrogen fixation for the plant.

[19] Leghemoglobin, produced by leguminous plants after colonization of S. meliloti, interacts with the free oxygen in the root nodule where the rhizobia reside.

However, E. meliloti mutants defective in either genes uvrA, uvrB or uvrC are sensitive to desiccation, as well as to UV light.