Epistle of Barnabas

The complete text is preserved in the 4th-century Codex Sinaiticus, where it appears at the end of the New Testament, following the Book of Revelation and before the Shepherd of Hermas.

It is mentioned in a perhaps third-century list in the sixth-century Codex Claromontanus and in the later Stichometry of Nicephorus appended to the ninth-century Chronography of Nikephoros I of Constantinople.

According to the epistle, the Jews had misinterpreted their own law (i.e., halakha) by applying it literally; the true meaning was to be found in its symbolic prophecies foreshadowing the coming of Jesus of Nazareth, who Christians believe to be the messiah.

The 4th-century Codex Sinaiticus (S), discovered by Constantin von Tischendorf in 1859 and published by him in 1862, contains a complete text of the Epistle placed after the canonical New Testament and followed by the Shepherd of Hermas.

The 11th-century Codex Hierosolymitanus (H), which also includes the Didache, the two Epistles of Clement and the longer version of the Letters of Ignatius of Antioch, is another witness to the full text.

A family of 10 or 11 manuscripts dependent on the 11th-century Codex Vaticanus graecus 859 (G) contain chapters 5:7b−21:9 placed as a continuation of a truncated text of Polycarp's letter to the Philippians (1:1–9:2).

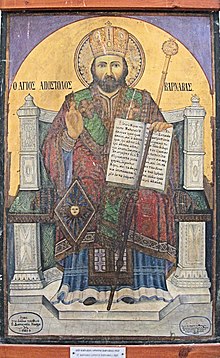

In the fourth century, the Epistle was also highly regarded by Didymus the Blind (c. 313 – c. 398),[13] Serapion of Thmuis (c. 290 – c. 358),[14] and Jerome (c. 342 – 420)[15] as an authentic work of the apostolic Barnabas.

[21][22] Next to the listing of Barnabas is a dash (most likely added some time later)[23] that may indicate doubtful or disputed canonicity, though the same marking is found next to 1 Peter as well, so its meaning is unclear.

Based on Koester's analysis (1957: 125–27, 157), it appears more likely that Barnabas stood in the living oral tradition used by the written gospels.

This demonstrates how the early Christian communities paid special attention to the exploration of Scripture in order to understand and tell the suffering of Jesus.

Barnabas still represents the initial stages of the process that is continued in the Gospel of Peter, later in Matthew, and is completed in Justin Martyr.

"[37] John Finnis has recently argued that the Epistle may have been written around the year 40 AD, proposing that chapter 16 refers instead to the destruction of the First Temple in 587 BC.

The place of origin must remain an open question, although the Gk-speaking E. Mediterranean appears most probable.The Epistle of Barnabas has the form not so much of a letter (it lacks indication of identity of sender and addressees), but as of a treatise.

The passion and death of Jesus at the hands of the Jews, it says, is foreshadowed in the properly understood rituals of the scapegoat (7) and the red heifer (8) and in the posture assumed by Moses in extending his arms (according to the Greek Septuagint text known to the author of the Epistle) in the form of the execution cross, while Joshua, whose name in Greek is Ἰησοῦς (Jesus), fought against Amalek (12).

He says that the work's two-part structure, with a distinct second part beginning with chapter 18, and its exegetical method "provide the most striking evidence of its Jewish perspective.

Finally, it applies biblical texts to its own contemporary historical situation in a manner reminiscent of the pesher technique found at Qumran.

[54] James L. Bailey judges as correct the classification as midrash of the frequent use by the evangelists of texts from the Hebrew Bible,[55] and Daniel Boyarin applies this in particular to the Prologue (1:1−18) of the Gospel of John.

[57] Other examples of midrash-like exegesis are found in the accounts of the temptation of Christ in Matthew and Luke,[58] and of circumstances surrounding the birth of Jesus.

In 1867, Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, in their Ante-Nicene Christian Library, disparaged the Epistle for what it called "the absurd and trifling interpretations of Scripture which it suggests".

[62] The Epistle of Barnabas also employs another technique of ancient Jewish exegesis, that of gematria, the ascription of religious significance to the numerical value of letters.

Now ΙΗ was a familiar contraction of the sacred name of Jesus, and is so written in the Alexandrian papyri of the period; and the letter Τ looked like the cross.

"[67] Robert A. Kraft states that some of the materials used by the final editor "certainly antedate the year 70, and are in some sense 'timeless' traditions of Hellenistic Judaism (e.g., the food law allegories of ch.

"[69] The author's style was not a personal foible: in his time it was accepted procedure in general use, although no longer in favour today.