Old Testament

Catholic and Orthodox churches include these, while most Protestant Bibles exclude them, though some Anglican and Lutheran versions place them in a separate section called Apocrypha.

Key debates have focused on the historicity of the Patriarchs, the Exodus, the Israelite conquest, and the United Monarchy, with archaeological evidence often challenging these narratives.

Mainstream scholarship has balanced skepticism with evidence, recognizing that some biblical traditions align with archaeological findings, particularly from the 9th century BC onward.

Several of the books in the Eastern Orthodox canon are also found in the appendix to the Latin Vulgate, formerly the official Bible of the Roman Catholic Church.

[10][aa] Similarities between the origin story of Moses and that of Sargon of Akkad were noted by psychoanalyst Otto Rank in 1909[14] and popularized by 20th-century writers, such as H. G. Wells and Joseph Campbell.

"[18] In 2022, archaeologist Avraham Faust summarized recent scholarship arguing that while early histories of Israel were heavily based on biblical accounts, their reliability has been increasingly questioned over time.

He continued that key debates have focused on the historicity of the Patriarchs, the Exodus, the Israelite conquest, and the United Monarchy, with archaeological evidence often challenging these narratives.

He concluded that while the minimalist school of the 1990s dismissed the Bible’s historical value, mainstream scholarship has balanced skepticism with evidence, recognizing that some biblical traditions align with archaeological findings, particularly from the 9th century BC onward.

[19] The first five books—Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, book of Numbers and Deuteronomy—reached their present form in the Persian period (538–332 BC), and their authors were the elite of exilic returnees who controlled the Temple at that time.

[20] The books of Joshua, Judges, Ruth, Samuel and Kings follow, forming a history of Israel from the Conquest of Canaan to the Siege of Jerusalem c. 587 BC.

There is a broad consensus among scholars that these originated as a single work (the so-called "Deuteronomistic History") during the Babylonian exile of the 6th century BC.

[26] The Old Testament stresses the special relationship between God and his chosen people, Israel, but includes instructions for proselytes as well.

As God is part of the agreement, and not merely witnessing it, The Jewish Study Bible instead interprets the term to refer to a pledge.

The Old Testament's moral code enjoins fairness, intervention on behalf of the vulnerable, and the duty of those in power to administer justice righteously.

The problem the Old Testament authors faced was that a good God must have had just reason for bringing disaster (meaning notably, but not only, the Babylonian exile) upon his people.

[34] The process by which scriptures became canons and Bibles was a long one, and its complexities account for the many different Old Testaments which exist today.

Timothy H. Lim, a professor of Hebrew Bible and Second Temple Judaism at the University of Edinburgh, identifies the Old Testament as "a collection of authoritative texts of apparently divine origin that went through a human process of writing and editing.

By about the 5th century BC, Jews saw the five books of the Torah (the Old Testament Pentateuch) as having authoritative status; by the 2nd century BC, the Prophets had a similar status, although without quite the same level of respect as the Torah; beyond that, the Jewish scriptures were fluid, with different groups seeing authority in different books.

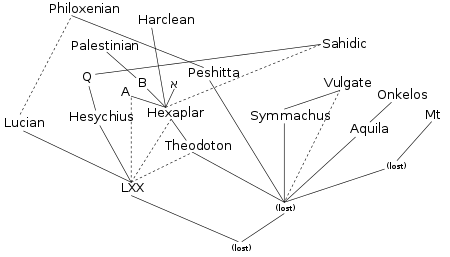

The so-called "fifth" and "sixth editions" were two other Greek translations supposedly miraculously discovered by students outside the towns of Jericho and Nicopolis: these were added to Origen's Octapla.

[49] Rome then officially adopted a canon, the Canon of Trent, which is seen as following Augustine's Carthaginian Councils[50] or the Council of Rome,[51][52] and includes most, but not all, of the Septuagint (3 Ezra and 3 and 4 Maccabees are excluded);[53] the Anglicans after the English Civil War adopted a compromise position, restoring the 39 Articles and keeping the extra books that were excluded by the Westminster Confession of Faith, both for private study and for reading in churches but not for establishing any doctrine, while Lutherans kept them for private study, gathered in an appendix as biblical apocrypha.

thought that the Messiah would be announced by a forerunner, probably Elijah (as promised by the prophet Malachi, whose book now ends the Old Testament and precedes Mark's account of John the Baptist).