Erich von Manstein

His memoir, Verlorene Siege (1955), translated into English as Lost Victories, was highly critical of Hitler's leadership, and dealt with only the military aspects of the war, ignoring its political and ethical contexts.

[8][9][10] After a period of home leave, on 17 June 1915, Manstein was reassigned as an assistant general staff officer of operations to the Tenth Army, commanded by Max von Gallwitz.

Soon promoted to captain, he learned first-hand how to plan and conduct offensive operations as the Tenth Army undertook successful attacks on Poland, Lithuania, Montenegro, and Albania.

That year he was promoted to major and served with the General Staff at the Reichswehr Ministry in Berlin, visiting other countries to learn about their military facilities and helping to draft mobilisation plans for the army.

However, officers like Ludwig Beck, Chief of the Army General Staff, were against such drastic changes, and therefore Manstein proposed an alternative: the development of Sturmgeschütze (StuG), self-propelled assault guns that would provide heavy direct-fire support to infantry.

[32] On 18 August 1939, in preparation for Fall Weiss (Case White) – the German invasion of Poland – Manstein was appointed Chief of Staff to Gerd von Rundstedt's Army Group South.

[34] He did become aware of the policy later on, as he and other Wehrmacht generals received reports[35][36] on the activities of the Einsatzgruppen, the Schutzstaffel (SS) death squads tasked with following the army into Poland to murder intellectuals and other civilians.

The flexibility and agility of the German forces led to the defeat of nine Polish infantry divisions and other units in the resulting Battle of the Bzura (8–19 September), the largest engagement of the war thus far.

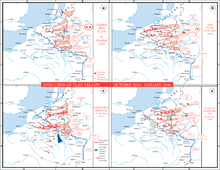

[40] Fall Gelb ("Case Yellow"), the initial plan for the invasion of France, was prepared by Commander-in-Chief of the Army Colonel General (Generaloberst) Walther von Brauchitsch, Halder, and other members of the OKH in early October 1939.

Manstein was not satisfied with the plan either, as it focused heavily on the northern wing; he felt an attack from this direction would lack the element of surprise and would expose the German forces to counterattacks from the south.

[43][44] Manstein's plan, developed with the informal co-operation of Heinz Guderian, suggested that the Panzer divisions attack through the wooded hills of the Ardennes where no one would expect them, then establish bridgeheads on the Meuse and rapidly drive to the English Channel.

His corps helped achieve the first breakthrough east of Amiens during Fall Rot ("Case Red" – the second phase of the invasion plan), and was the first to reach and cross the River Seine.

Aware of the need to act before the German offensive of 1942 reduced the availability of reinforcements and supplies, Manstein ordered a surprise attack across Severnaya Bay [ru] using amphibious landings on 29 June 1942.

[71][72][73][74] During the Crimean campaign Manstein was indirectly involved in atrocities against the Soviet population, especially those committed by Einsatzgruppe D, one of several Schutzstaffel (SS) groups that had been tasked with the elimination of the Jews of Europe.

[95][96] "Because of the sensitivity of the Stalingrad question in post-war Germany, Manstein worked as hard to distort the record on this matter as on his massive involvement in the murder of Jews", wrote Weinberg.

[98][99] Spurred on by this success, the Red Army planned a series of follow-up offensives in January and February 1943 intended to decisively beat the German forces in southern Russia.

[102] Hitler arrived at the front in person on 17 February, and over the course of three days of exhausting meetings, Manstein convinced him that offensive action was needed in the area to regain the initiative and prevent encirclement.

[107] Manstein favoured an immediate pincer attack on the Kursk salient after the battle at Kharkov, but Hitler was concerned that such a plan would draw forces away from the industrial region in the Donets Basin.

Meanwhile, the Red Army, well aware of the danger of encirclement, also moved in large numbers of reinforcements, and their intelligence reports revealed the expected locations and timing of the German thrusts.

With reinforcements trickling in, Manstein waged a series of counterattacks and armoured battles near Bohodukhiv and Okhtyrka between 13 and 17 August, which resulted in heavy casualties as they ran into prepared Soviet lines.

[127] Manstein correctly deduced that the next Soviet attack would be towards Kiev, but as had been the case throughout the campaign, the Red Army used maskirovka (deception) to disguise the timing and exact location of their intended offensive.

The German troops, thinking Bukrin would be the location of the main attack, were taken completely by surprise when Vatutin captured the bridgehead at Liutezh and gained a foothold on the west bank of the Dnieper.

[131] Under the guidance of General Hermann Balck, the cities of Zhytomyr and Korosten were retaken in mid-November,[130] but after receiving reinforcements Vatutin resumed the offensive on 24 December 1943,[132] and the Red Army continued its successful advance.

Without waiting for permission from Hitler, he ordered the German XI and XXXXII Corps (consisting of 56,000 men in six divisions) of Army Group South to break out of the Korsun Pocket during the night of 16–17 February 1944.

[137][138] Manstein received the Swords of the Knight's Cross on 30 March 1944[139] and handed over control of Army Group South to Model on 2 April during a meeting at Hitler's mountain retreat, the Berghof.

The myth that the Wehrmacht was "clean" – not culpable for the events of the Holocaust – arose partly as a result of this document, written largely by Manstein, along with General of Cavalry Siegfried Westphal.

British author B. H. Liddell Hart was in correspondence with Manstein and others at Island Farm and visited inmates of several camps around Britain while preparing his best-selling 1947 book On the Other Side of the Hill.

Charges included maltreatment of prisoners of war, co-operation with the Einsatzgruppe D in murdering Jewish residents of the Crimea, and disregarding the welfare of civilians by using "scorched earth" tactics while retreating from the Soviet Union.

[174] Biographer Benoît Lemay describes Manstein's actions as a reflection of his loyalty toward Hitler and the Nazi regime and of his grounding in a sense of duty based on traditional Prussian military values.

He has been described as a militärische Kult- und Leitfigur ("military cult figure and leading personality"), a general of legendary – almost mythical – ability, much honoured by both the public and historians.