Esselen

The Esselen are a Native American people belonging to a linguistic group in the hypothetical Hokan language family, who are Indigenous to the Santa Lucia Mountains of a region south of the Big Sur River in California.

Prior to Spanish colonization, they lived seasonally on the coast and inland, surviving off the plentiful seafood during the summer and acorns and wildlife during the rest of the year.

Like many Native American populations, their members were decimated by starvation, forced labor, over work, torture, and diseases that they had no natural resistance to.

[1] The people were believed to have been exterminated but some tribal members avoided the mission life and emerged from the forest to work in nearby ranches in the early and late 1800s.

One theory is that it refers to the name of a major native village, possibly Exse'ein, or the place called Eslenes (said to be near the current site of the Mission San Carlos).

[citation needed] On January 3, 1603, explorer Sebastián Vizcaíno found a deserted Indian village about a mile from what later became the site of the Carmel Mission.

This grammatical phenomenon, the most curious in this respect ever observed on the continent, will, perhaps, be interesting to those of the learned, who seek, in the analogy of languages, the history and genealogy of transplanted nations.In 1792, Spanish ship captain Dionisio Alcalá Galiano recorded 107 words and phrases.

[14] The Esselen resided along the upper Carmel and Arroyo Seco River, and along the Big Sur coast from near present-day Hurricane Point to the vicinity of Vicente Creek in the south.

[15] Carbon dating tests of artifacts found near Slates Hot Springs, presently owned by the Esalen Institute, indicate human presence as early as 3500 BC.

With easy access to the ocean, fresh water and hot springs, the Esselen people used the site regularly, and certain areas were reserved as burial grounds.

Explorer and later Governor of Alta California Pedro Fages described their dress in an account written before 1775: Nearly all of them go naked, except a few who cover themselves with a small cloak of rabbit or hare skin, which does not fall below the waist.

The women wear a short apron of red and white cords twisted and worked as closely as possible, which extends to the knee.

Others use the green and dry tule interwoven, and complete their outfit with a deerskin half tanned or entirely untanned, to make wretched underskirts which scarcely serve to indicate the distinction of sex, or to cover their nakedness with sufficient modesty.

[18] They followed local food sources seasonally, living near the coast in winter, where they harvested rich stocks of mussels, limpets, abalone and other sea life.

Spanish explorer Sebastián Vizcaíno reported, Their food consists of seeds which they have in great abundance and variety, and of the flesh of game such as deer, which are larger than cows, and bear, and of neat cattle and bisons and many other animals.

Miguel Constanso, who traveled with Portola's expeditions 175 years later, wrote about the homes of the Indians who lived on the Santa Barbara Channel.

They have vessels of pine wood very well made, in which they go to sea with fourteen paddle men on a side, with great dexterity, even in stormy weather.

He reckoned those qualities — along with the foggy and windy climate, shortage of potable water, high death rate, and language barriers — accounted for the painfully slow progress of mission Carmel.

These were replaced around the beginning of the 17th century with Repartimiento, which entitled a Spanish settler or official to the labor of a number of indigenous workers on their farms or mines.

The Spanish state based its right over the land and persons of the Indies on the Papal charge to evangelize the indigenous population.

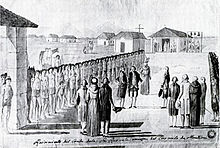

[36] The girls were separated from their families at age 8 and required to sleep in a segregated, locked dormitory called the monjero (nunnery).

The utter devastation caused by the white man was literally incredible, and not until the population figures are examined does the extent of the havoc become evident.

[12] However, existing tribe members cite evidence that some Esselen were able to move beyond the reach of the Spanish soldiers, who rode on horseback, by hiding in the rugged interior of the Santa Lucia Mountains.

[5][35] Archaeologists located the grave of a girl estimated to be about six years old buried in Isabel Meadows Cave in the Church Creek area.

But in 1899, anthropologist Alfred Kroeber declared that the tribe was extinct because most tribal members had intermarried, taken Spanish names, and converted to Catholicism.

[46]In 1955, Kroeber decided he had made a mistake and tried to persuade the BIA, but the agency refused to listen to his arguments or accept his evidence.

The ranch is located along the Little Sur River at the northwestern edge of the Ventana Wilderness adjacent to the Monterey Peninsula Regional Park District's Mill Creek Redwood Preserve and the Los Padres National Forest, and includes the peak of Bixby Mountain and the upper portions of Mescal Ridge.

[49][50][51] The nonprofit Western Rivers Conservancy, which buys land with the goal to protect habitat and provide public access, secured a purchase agreement.

It was initially interested in selling the land to the US Forest Service, which would make it possible for hikers to travel from Bottchers Gap to the sea.

[49][50] On October 2, 2019, the California Natural Resources Agency announced it was seeking funding through Proposition 68, a bond measure approved by voters in 2018, to obtain the land for the tribe.