Ester Boserup

[3] In an early review, her book was called "pioneering;" nearly five decades later, it has proved influential, having been cited by thousands of other works.

[5] The doctorates were in three different fields: agricultural, economic, and human sciences, respectively; the interdisciplinary nature of her work is reflected in these honors, just as it distinguished her career.

Ester had married Mogens Boserup when both were twenty-one; the young couple lived on his allowance from his well-off family during their remaining university years.

She and Mogens lived in Senegal for a year between 1964 and 1965, while he was leading the UN's effort to help establish the African Institute for Economic Development and Planning.

[5] Her first major work, The Conditions of Agricultural Growth: The Economics of Agrarian Change Under Population Pressure, laid out her thesis, informed by her experience in India in opposition to many views of the time.

Although Boserup is widely regarded as being anti-Malthusian, both her insights and those of Malthus can be comfortably combined within the same general theoretical framework.

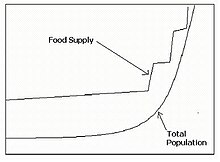

[9] Boserup argued that when population density is low enough to allow it, land tends to be used intermittently, with heavy reliance on fire to clear fields, and fallowing to restore fertility (often called slash and burn farming).

In Boserup's theory, it is only when rising population density curtails the use of fallowing (and therefore the use of fire) that fields are moved towards annual cultivation.

Although Boserup's original theory was highly simplified and generalized, it proved instrumental in understanding agricultural patterns in developing countries.

[6] In addition, according to the foreword in the 1989 edition by Swasti Mitter, "It is [Boserup's] committed and scholarly work that inspired the UN Decade for Women between 1975 and 1985, and that has encouraged aid agencies to question the assumption of gender neutrality in the costs as well as in the benefits of development".

Many liberal feminists took Boserup's analysis further to argue that the costs of modern economic development were shouldered by women.