ß

In German orthography, the letter ß, called Eszett (IPA: [ɛsˈtsɛt], S-Z) or scharfes S (IPA: [ˌʃaʁfəs ˈʔɛs], "sharp S"), represents the /s/ phoneme in Standard German when following long vowels and diphthongs.

[2] The Eszett letter is currently used only in German, and can be typographically replaced with the double-s digraph ⟨ss⟩, if the ß-character is unavailable.

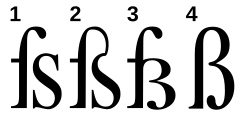

[3] The letter originates as the ⟨sz⟩ digraph as used in late medieval and early modern German orthography, represented as a ligature of ⟨ſ⟩ (long s) and ⟨ʒ⟩ (tailed z) in blackletter typefaces, yielding ⟨ſʒ⟩.

[5] Lowercase ⟨ß⟩ was encoded by ECMA-94 (1985) at position 223 (hexadecimal DF), inherited by Latin-1 and Unicode (U+00DF ß LATIN SMALL LETTER SHARP S).

[15][16] This is officially sanctioned by the reformed German orthography rules, which state in §25 E2: "In der Schweiz kann man immer „ss“ schreiben" ("In Switzerland, one may always write 'ss'").

[17]: 230 [18] Occasionally, ⟨ß⟩ has been used in unusual ways: As a result of the High German consonant shift, Old High German developed a sound generally spelled ⟨zz⟩ or ⟨z⟩ that was probably pronounced [s] and was contrasted with a sound, probably pronounced [s̠] (voiceless alveolar retracted sibilant) or [z̠] (voiced alveolar retracted sibilant), depending on the place in the word, and spelled ⟨s⟩.

[29] In the thirteenth century, the phonetic difference between ⟨z⟩ and ⟨s⟩ was lost at the beginning and end of words in all dialects except for Gottscheerish.

The earliest appearance of ligature resembling the modern ⟨ß⟩ is in a fragment of a manuscript of the poem Wolfdietrich from around 1300.

[17]: 214 [30] In the Gothic book hands and bastarda scripts of the late medieval period, ⟨sz⟩ is written with long s and the Blackletter "tailed z", as ⟨ſʒ⟩.

[17]: 217–18 In his Deutsches Wörterbuch (1854) Jacob Grimm called for ⟨ß⟩ or ⟨sz⟩ to be written for all instances of Middle and Old High German etymological ⟨z⟩ (e.g., eß instead of es from Middle High German: ez); however, his etymological proposal could not overcome established usage.

[32]: 269 In Austria-Hungary prior to the German Orthographic Conference of 1902, an alternative rule formulated by Johann Christian August Heyse in 1829 had been officially taught in the schools since 1879, although this spelling was not widely used.

Heyse's rule matches current usage after the German orthography reform of 1996 in that ⟨ß⟩ was only used after long vowels.

[31]: 73 German works printed in Roman type in the late 18th and early 19th centuries such as Johann Gottlieb Fichte's Wissenschaftslehre did not provide any equivalent to the ⟨ß⟩.

The formal abolition resulted in inconsistencies in how names are written in modern German (such as between Heuss and Heuß).

[17]: 221–22 The Education Council of Zürich had decided to stop teaching the letter in 1935, whereas the Neue Zürcher Zeitung continued to write ⟨ß⟩ until 1971.

[17]: 235 Because ⟨ß⟩ had been treated as a ligature, rather than as a full letter of the German alphabet, it had no capital form in early modern typesetting.

The preface to the 1925 edition of the Duden dictionary expressed the desirability of a separate glyph for capital ⟨ß⟩: Die Verwendung zweier Buchstaben für einen Laut ist nur ein Notbehelf, der aufhören muss, sobald ein geeigneter Druckbuchstabe für das große ß geschaffen ist.

[41]The use of two letters for a single phoneme is makeshift, to be abandoned as soon as a suitable type for the capital ß has been developed.The Duden was edited separately in East and West Germany during the 1950s to 1980s.

[44][45] A second proposal submitted in 2007 was successful, and the character was included in Unicode version 5.1.0 in April 2008 (U+1E9E ẞ LATIN CAPITAL LETTER SHARP S).

Most modern typefaces follow either 2 or 4, with 3 retained in occasional usage, notably in street signs in Bonn and Berlin.

[35]: 2 Use of typographic variants in street signs: The inclusion of a capital ⟨ẞ⟩ in Unicode in 2008 revived the century-old debate among font designers as to how such a character should be represented.

The code chart published by the Unicode Consortium favours the former possibility,[47] which has been adopted by Unicode capable fonts including Arial, Calibri, Cambria, Courier New, Dejavu Serif, Liberation Sans, Liberation Mono, Linux Libertine and Times New Roman; the second possibility is more rare, adopted by Dejavu Sans.

[48] In Germany and Austria, a 'ß' key is present on computer and typewriter keyboards, normally to the right-hand end on the number row.