Ethics in the Bible

This moral reasoning is part of a broad, normative covenantal tradition where duty and virtue are inextricably tied together in a mutually reinforcing manner.

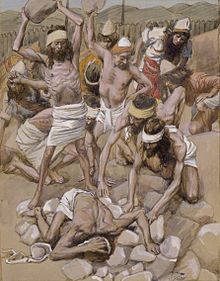

Some critics have viewed certain biblical teachings to be morally problematic and accused it of advocating for slavery, genocide, supersessionism, the death penalty, violence, patriarchy, sexual intolerance and colonialism.

There is a growing recognition it reflects the ethical values and norms of the educated class in ancient Israel, and that very little can be known about the moral beliefs of the 'ordinary' Israelites.

Descriptive philosophy is aimed purely at clarifying meaning and therefore, it has no difficulty "simply stating the nature of the diachronic variation and synchronic variability found in the biblical texts.

[3]: 211 It is "impossible to understand the Bible's fundamental structures of meaning without attending to the text's basic assumptions regarding reality, knowledge and value.

[3]: 157 First, Gericke says, metaphysics is found anywhere the Bible has something to say about "the nature of existence, reality, being, substance, mereology, time and space, causality, identity and change, objecthood and relations (e.g. subject and object), essence and accident, properties and functions, necessity and possibility (modality), order, mind and matter, freewill and determinism, and so on.

This moral reasoning is part of a broad normative covenantal tradition where duty and virtue are inextricably tied together in a mutually reinforcing manner.

[11]: xii First, the Hebrew Bible (the Old Testament) advocates monarchy in Jerusalem, and also supports notions of theocracy; the speech of Abijah of Judah in Chronicles 2 13:4–12 is taken as one of the purest expressions of this idea; Yahweh ordained only David and his progeny to rule in Jerusalem and only Aaron and his progeny to serve in the Temple, and any other claims to political or religious power or authority are against the will of God.

[13] Biblical descriptions of divinely ordained monarchy directly underlie the understanding of Jesus as the "son of David" and the messiah (the anointed king) who at some point will govern the world.

[14] Walzer says politics in the Bible is also similar to modern "consent theory" which requires agreement between the governed and the authority based on full knowledge and the possibility of refusal.

[11]: 5–6 Politics in the Bible also models "social contract theory" which says a person's moral obligations to form the society in which they live are dependent on that agreement.

[15] Walzer asserts this is what makes it possible for someone like Amos, "an herdsman and gatherer of sycamore fruit", to confront priests and kings, and remind them of their obligations.

"In the biblical texts, poor people, women, and even strangers, are recognized as moral agents in their own right whatever the extent of that agency might be.

"[23]: 27–58 Near Eastern scholar Yigal Levin, along with archaeologist Amnon Shapira, write that the ethic of war in the Bible is based on the concept of self-defense.

[25]: 270–274 In Exodus, Deuteronomy, Joshua, and both books of Kings, warfare includes narratives describing a variety of conflicts with Amalekites, Canaanites, and Moabites.

[11]: 42 However, starting in Joshua 9, after the conquest of Ai, Israel's battles are described as self-defense, and the priestly authors of Leviticus, and the Deuteronomists, are careful to give God moral reasons for his commandment.

[40] Holy war imagery is contained in the final book of the New Testament, Revelation, where John reconfigures traditional Jewish eschatology by substituting "faithful witness to the point of martyrdom for armed violence as the means of victory.

[41] Legal scholar Jonathan Burnside says biblical law is not fully codified, but it is possible to discern its key ethical elements.

[59]: 176 Near Eastern scholar Eve Levavi Feinstein writes "The concepts of pollution and sexuality seem inextricably linked", yet the views in the Bible vary more than is generally recognized.

Theologian Donald G. Bloesch infers that "Jesus called the Jewish women 'daughters of Abraham' (Luke 13:16), thereby according them a spiritual status equal to that of men.

New Testament scholar Ben Witherington III says "Jesus broke with both biblical and rabbinic traditions that restricted women's roles in religious practices, and He rejected attempts to devalue the worth of a woman, or her word of witness.

[66]: 1–7 As Harper says, "The church developed the radical notion of individual freedom centered around a libertarian paradigm of complete sexual agency.

[67]: 164 Margaret MacDonald demonstrates these dangerous circumstances were likely the catalysts for the "shift in perspective concerning unmarried women from Paul's [early] days to the time of the Pastoral epistles".

[67]: 164 [66]: 1–11 [67]: 164 The sexual-ethical structures of Roman society were built on status, and sexual modesty and shame meant something different for men than it did for women, and for the well-born than it did for the poor, and for the free citizen than it did for the slave.

[68][69] : 10, 38 [68] Harper says: "The model of normative sexual behavior that developed out of Paul's reactions to the erotic culture surrounding him...was a distinct alternative to the social order of the Roman empire.

[66]: 6, 7 Elizabeth Anderson, a Professor of Philosophy and Women's Studies at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, states that "the Bible contains both good and evil teachings", and it is "morally inconsistent".

[73] Anderson considers the Bible to permit slavery, the beating of slaves, the rape of female captives in wartime, polygamy (for men), the killing of prisoners, and child sacrifice.

[74] Simon Blackburn states that the "Bible can be read as giving us a carte blanche for harsh attitudes to children, the mentally handicapped, animals, the environment, the divorced, unbelievers, people with various sexual habits, and elderly women".

Blackburn provides examples of Old Testament moral criticisms, such as the phrase in Exodus 22:18, which he says has "helped to burn alive tens or hundreds of thousands of women in Europe and America": "Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live."

He states that the Old Testament God apparently has "no problems with a slave-owning society", considers birth control a crime punishable by death, and "is keen on child abuse".