The Bible and violence

The Hebrew Bible and the New Testament both contain narratives, poems, and instructions which describe, encourage, command, condemn, reward, punish and regulate violent actions by God,[1] individuals, groups, governments, and nation-states.

The noun which is derived from the verb (ḥērem[6]) is sometimes translated as "the ban" and it denotes the separation, exclusion and dedication of persons or objects to God which may be specially set apart for destruction (Deuteronomy 7:26; Leviticus 27:28-29).

[20] Levine says this indicates that Israel was still, as late as Deuteronomy, making ideological adjustments with regard to the importation of the foreign practice of ḥērem from its source in the surrounding Near Eastern nations.

[16]: 30 Old Testament professor Jerome F. D. Creach writes that Genesis 1 and 2 present two claims that "set the stage for understanding violence in the rest of the Bible": first is the declaration the God of the Hebrews created without violence or combat which runs counter to other Near Eastern creation stories; second, these opening chapters appoint humans as divine representatives on earth as caretakers, to "establish and maintain the well-being or shalom of the whole creation".

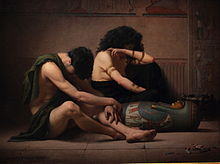

In Genesis 4:1–18, the Hebrew word for sin (hattā't) appears for the first time when Cain, the first born man, murders his brother Abel and commits the first recorded act of violence.

On the other hand, God promises that if his people obey him, he will protect them from the diseases the surrounding nations suffer from and give them victory in fighting their enemies in Deuteronomy 6, 7 and 11.

They are also used both separately and in combination throughout the remainder of the Hebrew Bible describing robbing the poor (Isaiah 3:14, 10:2; Jeremiah 22:3; Micah 2:2, 3:2; Malachi 1:3), withholding the wages of a hired person (cf.

But you shall utterly destroy (ha-harem taharimem) them, the Hittite and the Amorite, the Canaanite and the Perizzite, the Hivite and the Jebusite, as the Lord your God has commanded you…" exempting only the fruit trees.

[6]: 8 UCL historian Hans Van Wees (2010) has stated: 'The genocidal campaigns claimed for the early Israelites, however, are largely fictional: the intrinsic improbability and internal inconsistencies of the account in Joshua and its incompatibility with the stories of Judges leave little doubt about this.

"If men get into a fight with one another, and the wife of one intervenes to rescue her husband from the grip of his opponent by reaching out and seizing his genitals, you shall cut off her hand; show no pity" (25:11–12),[63][64] although rabbinical scholars debate whether this is to be interpreted as a requirement for self defense, or a metaphor for financial liability.

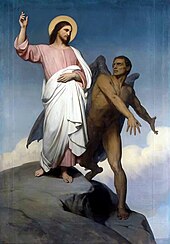

[103] For example, Jesus uses apocalyptic speech in Matthew 10:15 when he says "it will be more bearable for Sodom and Gomorrah on the day of judgment than for that town," and in Mark 14:62, where he alludes to the book of Daniel with himself in the future "sitting at the right hand of God."

[105][106] According to Richard Bauckham, the author of the book of Revelation addresses apocalypse with a reconfiguration of traditional Jewish eschatology that substitutes "faithful witness to the point of martyrdom for armed violence as the means of victory.

Historian Paul Copan and philosopher Matthew Flannagan say the violent texts of ḥerem warfare are "hagiographic hyperbole", a kind of historical writing found in the Book of Joshua and other Near Eastern works of the same era and are not intended to be literal; they contain hyperbole, formulaic language, and literary expressions for rhetorical effect — like when sports teams use the language of “totally slaughtering” their opponents.

[108] John Gammie concurs, saying the Bible verses about "utterly destroying" the enemy are more about pure religious devotion than an actual record of killing people.

He writes that: "....historically people have appealed to the Bible precisely because of its presumed divine authority, which gives an aura of certitude to any position it can be shown to support -- in the phrase of Hannah Arendt, 'God-like certainty that stops all discussion.'

The full canonical shape of the Christian Bible, for what it is worth, still concludes with the judgement scene in Revelation, in which the Lamb that was slain returns as the heavenly warrior with a sword for striking down the nations.

[113]: 18–19 Near the end of her book, she says: "My re-vision would produce an alternative Bible that subverts the dominant vision of violence and scarcity with an ideal of plenitude and its corollary ethical imperative of generosity.

"[115] Evan Fales, Professor of Philosophy, calls the doctrine of substitutionary atonement that some Christians use to understand the crucifixion of Jesus, "psychologically pernicious" and "morally indefensible".

[127]: 30 The soul-making theodicy advocated by John Hick says God allows the evil of suffering because it produces good in its results of building moral character.

[128] Christian ethicists such as David Ray Griffin have also produced process theodicies which assert God's power and ability to influence events are, of necessity, limited by human creatures with wills of their own.

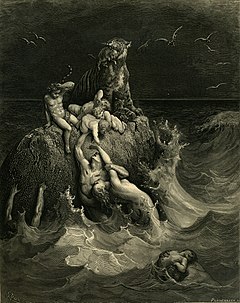

"[6]: 4 Canaanite creation stories like the Enuma Elish use very physical terms such as "tore open," "slit," "threw down," "smashed," and "severed" whereas in the Hebrew Bible, Leviathan is not so much defeated as domesticated.

[137]: 69, 70 Theologian Christopher Hays says Hebrew stories use a term for dividing (bâdal; separate, make distinct) that is an abstract concept more reminiscent of a Mesopotamian tradition using non-violence at creation.

[6]: 14 [146] The term for peace in the Hebrew Bible is SH-L-M.[147] It is used to describe prophetic vision and ideal conditions,[148]: 32, 2 and theologians have built on passages referencing it to advocate for various forms of social justice.

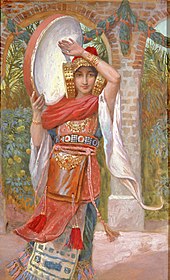

[152]: 22 [153] : 14 [150] More evidence comes from Second Maccabees, written in the second century BCE, containing the dying words of seven pious Jewish brothers and their mother who have full confidence in their physical resurrection by Yahweh.

[156]: 38 For example, the early church father Origen [c. 184 – c. 253] "believed that after death there were many who would need prolonged instruction, the sternest discipline, even the severest punishment before they were fit for the presence of God.

After the church decided Augustine had sufficiently proven the existence of an eternal Hell for them to adopt it as official dogma, the Synod of Constantinople met in 543, and excommunicated the long dead Origen on 15 separate charges of anathema.

Marcion considered Jesus' universal God of compassion and love, who looks upon humanity with benevolence and mercy, incompatible with Old Testament depictions of divinely ordained violence.

[167]: 2, 4 Anders Gerdmar [sv] sees the development of anti-semitism as part of the paradigm shift that occurred in early modernity when the new scientific focus on the Bible and history replaced the primacy of theology and tradition.

While the ancient Israelites conceived of their deity as one being in contrast to the polytheistic conception of its neighbors, they remained like other ANE peoples in considering themselves a single whole unit in relationship with god.

It incites to "counterpower," to "positive" criticism, to an irreducible dialogue (like that between king and prophet in Israel), to antistatism, to a decentralizing of the relation, to an extreme relativizing of everything political, to an anti-ideology, to a questioning of all that claims either power or dominion (in other words, of all things political)...Throughout the Old Testament we see God choosing what is weak and humble to represent him (the stammering Moses, the infant Samuel, Saul from an insignificant family, David confronting Goliath, etc.).