Ethiopian art

[3] Although some buildings and large, pre-Christian stelae exist, there appears to be no surviving Ethiopian Christian art from the Axumite period.

[5] However, the 7th-century AD followers of the Islamic prophet Muhammad who fled to Axum in temporary exile mentioned that the original Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion was decorated with paintings.

[6] Ethiopian painting, on walls, in books, and in icons,[7] is highly distinctive, though the style and iconography are closely related to the simplified Coptic version of Late Antique and Byzantine Christian art.

One of the best-known examples of this type of painting is at Debre Berhan Selassie in Gondar (pictured), famed for its angel-covered roof (angels in Ethiopian art are often represented as winged heads) as well as its other murals dating from the late 17th century.

[9] Pilgrimages to Jerusalem, where there has long been an Ethiopian clerical presence, also allowed some contact with a wider range of Orthodox art.

She is often depicted with a neighboring image of a mounted Saint George and the Dragon, who is regarded as especially linked to Mary in Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity, for carrying messages or intervening in human affairs on her behalf.

Distinctive forms of the crown were worn in ceremonial contexts by royalty and important noble officials, as well as senior clergy.

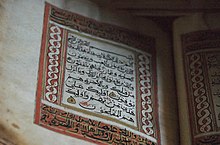

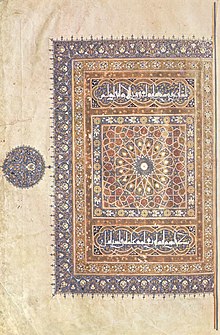

[14] The confluence of culture from both nomadic groups indigenous to the region and trade partners beyond, resulted in a style of manuscript unique to the Harari people.

The Khalili manuscript (a single-volume Qur’ān of 290 folios) is regarded by scholar Dr. Sana Mirza as representative of distinct Harari codices (known in Arabic as Mus'haf).

[14] Beyond the script, Ajami represents the contextual enrichment of Islamic traditions within the region during this period more broadly, a process growing literature on the subject refers to as Ajamization.

The Ajamization of Qur’ānic texts by the Harari people, reflects this intersection of assimilation and preservation, through adapting traditional Islamic practices to indigenous culture and taste.

Transcultural parallels and adaptations in the illumination of the text, such as the Byzantine influence on Christian illustrations within the region, can also be observed in Islamic art.

[15] Notably, Dr. Mirza has drawn parallels between the Harari manuscripts and the decorative devices from the Islamic texts of the Mamluk Sultanate (modern-day Egypt and Syria) and the calligraphic letterform of the Biḥārī script (northeast India).

[15] The lack of representation for Islamic manuscripts compared to other religious texts from Ethiopia in mainstream scholarship can be attributed to a variety of reasons.

A leading scholar in Islamic manuscript cultures in Sub-Saharan Africa, Dr. Alessandro Gori, ascribes this disproportionate representation within academia to a variety of socio-political factors.

[17] This privatization made it easier for collectors from Europe, the United States, and Arab countries to acquire these texts without going through institutional channels.

[18] In conjunction with the destruction of manuscripts by foreign aggressors or disputing citizens,[17] lack of trust in government bodies, and smuggling;[18] cataloging and preserving these sacred texts remains a difficult task.

In collaboration with the Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Dr. Gori published a catalog of Islamic codices in 2014 to help facilitate future research on these manuscripts.