Ethiopian wolf

Threats include increasing pressure from expanding human populations, resulting in habitat degradation through overgrazing, and disease transference and interbreeding from free-ranging dogs.

[14][15] European writers traveling in Ethiopia during the mid-19th century (then called Abyssinia by Europeans and Ze Etiyopia by its citizens), wrote that the animal's skin was never worn by natives, as it was popularly believed that the wearer would die should any wolf hairs enter an open wound,[16] while Charles Darwin hypothesised that the species gave rise to greyhounds.

[17][b] Since then, it was scarcely heard of in Europe up until the early 20th century, when several skins were shipped to England by Major Percy Powell-Cotton during his travels in Abyssinia.

The IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group advocated a three-front strategy of education, wolf population monitoring, and rabies control in domestic dogs.

The surveys taken revealed local extinctions in Mount Choqa, Gojjam, and in every northern Afroalpine region where agriculture is well developed and human pressure acute.

This changed about 15,000 years ago with the onset of the current interglacial, which caused the species' Afroalpine habitat to fragment, thus isolating Ethiopian wolf populations from each other.

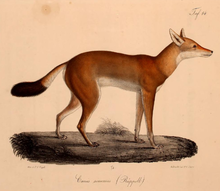

[6] The Ethiopian wolf is one of five Canis species present in Africa, and is readily distinguishable from jackals by its larger size, relatively longer legs, distinct reddish coat, and white markings.

John Edward Gray and Glover Morrill Allen originally classified the species under a separate genus, Simenia,[21] and Oscar Neumann considered it to be "only an exaggerated fox".

The thickly furred tail is white underneath, and has a black tip, though, unlike most other canids, there is no dark patch marking the supracaudal gland.

[5] Animals resulting from Ethiopian wolf-dog hybridisation tend to be more heavily built than pure wolves, and have shorter muzzles and different coat patterns.

[27] The Ethiopian wolf is a social animal, living in family groups containing up to 20 adults (individuals older than one year), though packs of six wolves are more common.

In areas with little food, the species lives in pairs, sometimes accompanied by pups, and defends larger territories averaging 13.4 km2 (5.2 sq mi).

If he is unsuccessful, he seems to lose his temper, and starts digging violently; but this is only lost labour, as the ground is honeycombed with holes, and every rat is yards away before he has thrown up a pawful.

[35]The technique described above is commonly used in hunting big-headed African mole-rats, with the level of effort varying from scratching lightly at the hole to totally destroying a set of burrows, leaving metre-high earth mounds.

Its ideal habitat extends from above the tree line around 3,200 to 4,500 m, with some wolves inhabiting the Bale Mountains being present in montane grasslands at 3,000 m. Although specimens were collected in Gojjam and northwestern Shoa at 2,500 m in the early 20th century, no recent records exist of the species occurring below 3,000 m. In modern times, subsistence agriculture, which extends up to 3,700 m, has largely restricted the species to the highest peaks.

Prime wolf habitat in the Bale Mountains consists of short Alchemilla herbs and grasses, with low vegetation cover.

Suitable areas of land below this limit are under some level of protection, such as Guassa-Menz and the Denkoro Reserve, or within the southern highlands, such as the Arsi and Bale Mountains.

The most vulnerable wolf populations to habitat loss are those within relatively low-lying Afroalpine ranges, such as those in Aboi Gara and Delanta in North Wollo.

[45] Some Ethiopian wolf populations, particularly those in North Wollo, show signs of high fragmentation, which is likely to increase with current rates of human expansion.

The dangers posed by fragmentation include increased contact with humans, dogs, and livestock, and further risk of isolation and inbreeding in wolf populations.

Although no evidence of inbreeding depression or reduced fitness exists, the extremely small wolf population sizes, particularly those north of the Rift Valley, raise concerns among conservationists.

Although no declines in wolf populations related to overgrazing have occurred, high grazing intensities are known to lead to soil erosion and vegetation deterioration in Afroalpine areas such as Delanta and Simien.

Although people living close to wolves in modern times believe that wolf populations are recovering, negative attitudes towards the species persist due to livestock predation.

Although hybridization has not been detected elsewhere, scientists are concerned that it could pose a threat to the wolf population's genetic integrity, resulting in outbreeding depression or a reduction in fitness, though this does not appear to have taken place.

[27] Due to the female's strong preference to avoid inbreeding, hybridization could be the result of not finding any males who are not close relatives outside of dogs.

Areas of suitable wolf habitat have recently increased to 87%, as a result of boundary extensions in Simien and the creation of the Arsi Mountains National Park.

[2] The species' critical situation was first publicised by the Wildlife Conservation Society in 1983, with the Bale Mountains Research Project being established shortly after.

[2] The overall aim of the EWCP is to protect the wolf's Afroalpine habitat in Bale, and establish additional conservation areas in Menz and Wollo.

The EWCP carries out education campaigns for people outside the wolf's range to improve dog husbandry and manage diseases within and around the park, as well as monitoring wolves in Bale, south and north Wollo.

[2] In 2016, the Korean company Sooam Biotech was reported to be attempting to clone the Ethiopian wolf using dogs as surrogate mothers to help conserve the species.