Euler equations (fluid dynamics)

[4] Prior work included contributions from the Bernoulli family as well as from Jean le Rond d'Alembert.

During the second half of the 19th century, it was found that the equation related to the balance of energy must at all times be kept for compressible flows, and the adiabatic condition is a consequence of the fundamental laws in the case of smooth solutions.

For example, with density nonuniform in space but constant in time, the continuity equation to be added to the above set would correspond to:

[7] Smooth solutions of the free (in the sense of without source term: g=0) equations satisfy the conservation of specific kinetic energy:

Substitution of these inversed relations in Euler equations, defining the Froude number, yields (omitting the * at apix):

The limit of high Froude numbers (low external field) is thus notable and can be studied with perturbation theory.

In differential convective form, the compressible (and most general) Euler equations can be written shortly with the material derivative notation:

meaning that for an incompressible inviscid nonconductive flow a continuity equation holds for the internal energy.

since the internal energy in thermodynamics is a function of the two variables aforementioned, the pressure gradient contained into the momentum equation should be explicited as:

We remark that also the Euler equation even when conservative (no external field, Froude limit) have no Riemann invariants in general.

Expanding the fluxes can be an important part of constructing numerical solvers, for example by exploiting (approximate) solutions to the Riemann problem.

If one considers Euler equations for a thermodynamic fluid with the two further assumptions of one spatial dimension and free (no external field: g = 0):

where n is the number density, and T is the absolute temperature, provided it is measured in energetic units (i.e. in joules) through multiplication with the Boltzmann constant.

By substituting this ratio in the Newton–Laplace law, the expression of the sound speed into an ideal gas as function of temperature is finally achieved.

Lamb in his famous classical book Hydrodynamics (1895), still in print, used this identity to change the convective term of the flow velocity in rotational form:[14]

the Euler momentum equation assumes a form that is optimal to demonstrate Bernoulli's theorem for steady flows:

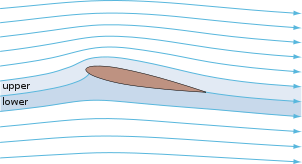

And by projecting the momentum equation on the flow direction, i.e. along a streamline, the cross product disappears because its result is always perpendicular to the velocity:

That is, the momentum balance for a steady inviscid and incompressible flow in an external conservative field states that the total head along a streamline is constant.

The right-hand side appears on the energy equation in convective form, which on the steady state reads:

Since the external field potential is usually small compared to the other terms, it is convenient to group the latter ones in the total enthalpy:

In the steady case the two variables entropy and total enthalpy are particularly useful since Euler equations can be recast into the Crocco's form:

From these relationships one deduces that the specific total free energy is uniform in a steady, irrotational, isothermal, isoentropic, inviscid flow.

Then, weak solutions are formulated by working in 'jumps' (discontinuities) into the flow quantities – density, velocity, pressure, entropy – using the Rankine–Hugoniot equations.

(See Navier–Stokes equations) Shock propagation is studied – among many other fields – in aerodynamics and rocket propulsion, where sufficiently fast flows occur.

This global form simply states that there is no net flux of a conserved quantity passing through a region in the case steady and without source.

On the other hand the ideal gas law is less strict than the original fundamental equation of state considered.

Now inverting the equation for temperature T(e) we deduce that for an ideal polytropic gas the isochoric heat capacity is a constant:

This equation states:In a steady flow of an inviscid fluid without external forces, the center of curvature of the streamline lies in the direction of decreasing radial pressure.

Although this relationship between the pressure field and flow curvature is very useful, it doesn't have a name in the English-language scientific literature.

[26] This "theorem" explains clearly why there are such low pressures in the centre of vortices,[25] which consist of concentric circles of streamlines.