Krill

Most krill species display large daily vertical migrations, providing food for predators near the surface at night and in deeper waters during the day.

The most familiar and largest group of crustaceans, the class Malacostraca, includes the superorder Eucarida comprising the three orders, Euphausiacea (krill), Decapoda (shrimp, prawns, lobsters, crabs), and the planktonic Amphionidacea.

[5] The lesser-known family, the Bentheuphausiidae, has only one species, Bentheuphausia amblyops, a bathypelagic krill living in deep waters below 1,000 m (3,300 ft).

[7] Bentheuphausia Thysanopoda (♣) Nematobrachion (♦) Meganyctiphanes Pseudeuphausia Euphausia Nyctiphanes Nematoscelis Thysanoessa Tessarabrachion Stylocheiron As of 2013[update], the order Euphausiacea is believed to be monophyletic due to several unique conserved morphological characteristics (autapomorphy) such as its naked filamentous gills and thin thoracopods[10] and by molecular studies.

[10] It was later also proposed that order Euphausiacea should be grouped with the Penaeidae (family of prawns) in the Decapoda based on developmental similarities, as noted by Robert Gurney and Isabella Gordon.

[10] Molecular studies have not unambiguously grouped them, possibly due to the paucity of key rare species such as Bentheuphausia amblyops in krill and Amphionides reynaudii in Eucarida.

[19] All dating of speciation events were estimated by molecular clock methods, which placed the last common ancestor of the krill family Euphausiidae (order Euphausiacea minus Bentheuphausia amblyops) to have lived in the Lower Cretaceous about 130 million years ago.

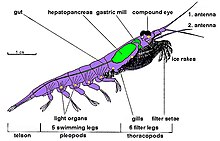

They have anatomy similar to a standard decapod with their bodies made up of three parts: the cephalothorax is composed of the head and the thorax, which are fused, and the abdomen, which bears the ten swimming appendages, and the tail fan.

Krill are probably the sister clade of decapods because all species have five pairs of swimming legs called "swimmerets" in common with the latter, very similar to those of a lobster or freshwater crayfish.

[39] The precise function of these organs is as yet unknown; possibilities include mating, social interaction or orientation and as a form of counter-illumination camouflage to compensate their shadow against overhead ambient light.

Krill convert the primary production of their prey into a form suitable for consumption by larger animals that cannot feed directly on the minuscule algae.

Northern krill and some other species have a relatively small filtering basket and actively hunt copepods and larger zooplankton.

[47] Several single-celled endoparasitoidic ciliates of the genus Collinia can infect species of krill and devastate affected populations.

[51] Preliminary research indicates krill can digest microplastics under 5 mm (0.20 in) in diameter, breaking them down and excreting them back into the environment in smaller form.

By that time their yolk reserves are exhausted and the larvae must have reached the photic zone, the upper layers of the ocean where algae flourish.

[53] After the final furcilia stage, an immature juvenile emerges in a shape similar to an adult, and subsequently develops gonads and matures sexually.

[54] During the mating season, which varies by species and climate, the male deposits a sperm sack at the female's genital opening (named thelycum).

[25] The 57 species of the genera Bentheuphausia, Euphausia, Meganyctiphanes, Thysanoessa, and Thysanopoda are "broadcast spawners": the female releases the fertilised eggs into the water, where they usually sink, disperse, and are on their own.

[60] Similar shrinkage has also been observed for E. pacifica, a species occurring in the Pacific Ocean from polar to temperate zones, as an adaptation to abnormally high water temperatures.

In 2012, Gandomi and Alavi presented what appears to be a successful stochastic algorithm for modelling the behaviour of krill swarms.

The algorithm is based on three main factors: " (i) movement induced by the presence of other individuals (ii) foraging activity, and (iii) random diffusion.

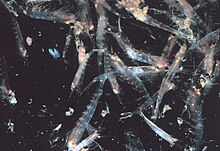

Some species (e.g., Euphausia superba, E. pacifica, E. hanseni, Pseudeuphausia latifrons, and Thysanoessa spinifera) form surface swarms during the day for feeding and reproductive purposes even though such behaviour is dangerous because it makes them extremely vulnerable to predators.

When in danger, they show an escape reaction called lobstering—flicking their caudal structures, the telson and the uropods, they move backwards through the water relatively quickly, achieving speeds in the range of 10 to 27 body lengths per second, which for large krill such as E. superba means around 0.8 m/s (3 ft/s).

[72] Their swimming performance has led many researchers to classify adult krill as micro-nektonic life-forms, i.e., small animals capable of individual motion against (weak) currents.

[75][76] It plays a prominent role in the Southern Ocean because of its ability to cycle nutrients and to feed penguins and baleen and blue whales.

Krill have been harvested as a food source for humans and domesticated animals since at least the 19th century, and possibly earlier in Japan, where it was known as okiami.

[80] Major countries involved in krill harvesting are Norway (56% of total catch in 2014), the Republic of Korea (19%), and China (18%).

[84] In 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration published a letter of no objection for a manufactured krill oil product to be generally recognized as safe (GRAS) for human consumption.

are most widely consumed in Southeast Asia, where it is fermented (with the shells intact) and usually ground finely to make shrimp paste.

It can be stir-fried and eaten paired with white rice or used to add umami flavors to a wide variety of traditional dishes.