Eurozone

[9] Among non-EU member states, Andorra, Monaco, San Marino, and Vatican City have formal agreements with the EU to use the euro as their official currency and issue their own coins.

The European Central Bank (ECB) makes monetary policy for the eurozone, sets its base interest rate, and issues euro banknotes and coins.

Since the financial crisis of 2007–2008, the eurozone has established and used provisions for granting emergency loans to member states in return for enacting economic reforms.

[16] In 1998, eleven member states of the European Union had met the euro convergence criteria, and the eurozone came into existence with the official launch of the euro (alongside national currencies) on 1 January 1999 in those countries: Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain.

Four states (Andorra, Monaco, San Marino, and Vatican City) have signed formal agreements with the EU to use the euro and issue their own coins.

[34] The chart below provides a full summary of all applying exchange-rate regimes for EU members, since the birth, on 13 March 1979, of the European Monetary System with its Exchange Rate Mechanism and the related new common currency ECU.

Sources: EC convergence reports 1996-2014, Italian lira, Spanish peseta, Portuguese escudo, Finnish markka, Greek drachma, Sterling The eurozone was born with its first 11 member states on 1 January 1999.

In September 2011, a diplomatic source close to the euro adoption preparation talks with the seven remaining new member states who had yet to adopt the euro at that time (Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania), claimed that the monetary union (eurozone) they had thought they were going to join upon their signing of the accession treaty may very well end up being a very different union, entailing a much closer fiscal, economic, and political convergence than originally anticipated.

This changed legal status of the eurozone could potentially cause them to conclude that the conditions for their promise to join were no longer valid, which "could force them to stage new referendums" on euro adoption.

[35] Seven countries (Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden) are EU members but do not use the euro.

Denmark obtained a special opt-out in the original Maastricht Treaty, and thus is legally exempt from joining the eurozone unless its government decides otherwise, either by parliamentary vote or referendum.

[40] In the opinion of journalist Leigh Phillips and Locke Lord's Charles Proctor,[41][42] there is no provision in any European Union treaty for an exit from the eurozone.

"[45] It added that it "does not intend to propose [any] amendment" to the relevant Treaties, the current status being "the best way going forward to increase the resilience of euro area Member States to potential economic and financial crises.

[47] Some, however, including the Dutch government, favour the creation of an expulsion provision for the case whereby a heavily indebted state in the eurozone refuses to comply with an EU economic reform policy.

[51][52][53] Since the global financial crisis of 2007–2008, the Euro Group has met irregularly not as finance ministers, but as heads of state and government (like the European Council).

These guidelines are not binding, but are intended to represent policy coordination among the EU member states, so as to take into account the linked structures of their economies.

Subsequently, reforms were adopted to provide more flexibility and ensure that the deficit criteria took into account the economic conditions of the member states, and additional factors.

The Fiscal Compact[69][70] (formally, the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union),[71] is an intergovernmental treaty introduced as a new stricter version of the Stability and Growth Pact, signed on 2 March 2012 by all member states of the European Union (EU), except the Czech Republic, the United Kingdom,[72] and Croatia (subsequently acceding the EU in July 2013).

But he adds that the currency bloc will not work perfectly even if a fiscal transfer system is built, because, he argues, the fundamental issue about competitiveness adjustment is not tackled.

Therefore, it was agreed in 2011 to establish a European Stability Mechanism (ESM) which would be much larger, funded only by eurozone states (not the EU as a whole as the EFSF/EFSM were) and would have a permanent treaty basis.

[75] In June 2010, a broad agreement was finally reached on a controversial proposal for member states to peer review each other's budgets prior to their presentation to national parliaments.

Although showing the entire budget to each other was opposed by Germany, Sweden and the UK, each government would present to their peers and the Commission their estimates for growth, inflation, revenue and expenditure levels six months before they go to national parliaments.

[78][79] In 1997, Arnulf Baring expressed concern that the European Monetary Union would make Germans the most hated people in Europe.

Baring suspected the possibility that the people in Mediterranean countries would regard Germans and the currency bloc as economic policemen.

[80] In 2001, James Tobin thought that the euro project would not succeed without making drastic changes to European institutions, pointing out the difference between the US and the eurozone.

[81] Concerning monetary policies, the system of Federal Reserve banks in the US aims at both growth and reducing unemployment, while the ECB tends to give its first priority to price stability under the Bundesbank's supervision.

[82] Oliver Hart, who received the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 2016, criticized the euro, calling it a "mistake" and emphasising his opposition to monetary union since its inception.

"[88] Matthias Matthijs believes that the euro resulted in a "winner-take-all" economy, as national income differences between eurozone members have widened further.

[98] In 2020, a study from the University of Bonn reached a different conclusion: the adoption of the euro made “some mild losers (France, Germany, Italy, and Portugal) and a clear winner (Ireland)”.

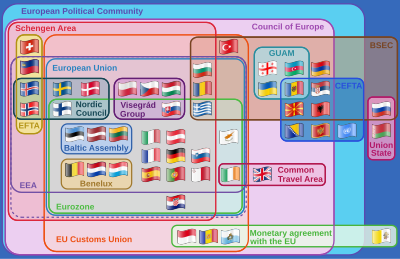

- European Union member states ( special territories not shown)

-

20 in the eurozone5 not in ERM II, but obliged to join the eurozone on meeting the convergence criteria ( Czech Republic , Hungary , Poland , Romania , and Sweden )

- Non–EU member states