Eurobond (eurozone)

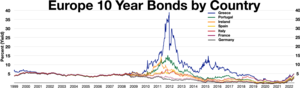

[1] The proposal was generally favored by indebted governments such as Portugal, Greece, and Ireland, but encountered strong opposition, notably from Germany, the eurozone's strongest economy.

Participating countries must also establish an Independent Stability Council voted on by member states parliaments to propose annually an allocation for the blue bond and to safeguard fiscal responsibility.

[3] The authors argue that while their concept is not a quick fix, their Blue Bond proposal charts an incentive-driven and durable way out of the debt dilemma while "helping prepare the ground for the rise of the euro as an important reserve currency, which could reduce borrowing costs for everybody involved".

On 23 November 2011 the Commission presented a Green Paper assessing the feasibility of common issuance of sovereign bonds among the EU member states of the eurozone.

The introduction of commonly issued eurobonds would mean a pooling of sovereign issuance among the member states and the sharing of associated revenue flows and debt-servicing costs.

[4] According to the European Commission proposal the introduction of eurobonds would create new means through which governments finance their debt, by offering safe and liquid investment opportunities.

The effect would be immediate even if the introduction of eurobonds takes some time, since changed market expectations adapt instantly, resulting in lower average and marginal funding costs, particularly to those EU member states most hit by the financial crisis.

[11] Hans-Werner Sinn from the Munich-based Ifo Institute for Economic Research believes the cost for German tax payers to be between 33 and 47 billion Euros per year.

"[16] Presenting the idea of "stability bonds", Jose Manuel Barroso insisted that any such plan would have to be matched by tight fiscal surveillance and economic policy co-ordination as an essential counterpart so as to avoid moral hazard and ensure sustainable public finances.

The commission would then be able to ask the government to revise the budget if it believed that it was not sound enough to meet its targets for debt and deficit levels as set out in the Euro convergence criteria.

[19] On 9 December 2011 at the European Council meeting, all 17 members of the euro zone and six states that aspire to join agreed on a new intergovernmental treaty to put strict caps on government spending and borrowing, with penalties for those countries that violate the limits.

[21] Italy and Greece have frequently spoken out in favour of eurobonds, the then Italian Minister of economy Giulio Tremonti calling it the "master solution" to the eurozone debt crisis.

Bulgarian finance minister Simeon Djankov criticised eurobonds [citation needed] in Austria's Der Standard: "Cheap credit got us into the current eurozone crisis, it's naive to think it is going to get us out of it."

[31] Spanish and Italian leaders have called for jointly issued "corona bonds" in order to help their countries, hard-hit by the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019, to recover from the epidemic.