Eutectic system

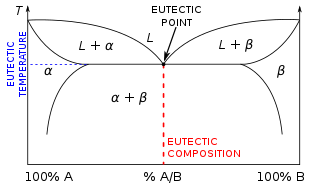

[2] The lowest possible melting point over all of the mixing ratios of the constituents is called the eutectic temperature.

Conversely, as a non-eutectic mixture cools down, each of its components solidifies into a lattice at a different temperature, until the entire mass is solid.

In the real world, eutectic properties can be used to advantage in such processes as eutectic bonding, where silicon chips are bonded to gold-plated substrates with ultrasound, and eutectic alloys prove valuable in such diverse applications as soldering, brazing, metal casting, electrical protection, fire sprinkler systems, and nontoxic mercury substitutes.

The term eutectic was coined in 1884 by British physicist and chemist Frederick Guthrie (1833–1886).

[2] Before his studies, chemists assumed "that the alloy of minimum fusing point must have its constituents in some simple atomic proportions", which was indeed proven to be not the case.

Tangibly, this means the liquid and two solid solutions all coexist at the same time and are in chemical equilibrium.

[6] Compositions of eutectic systems that are not at the eutectic point can be classified as hypoeutectic or hypereutectic: As the temperature of a non-eutectic composition is lowered the liquid mixture will precipitate one component of the mixture before the other.

Conversely, when a well-mixed, eutectic alloy melts, it does so at a single, sharp temperature.

A second tunable strengthening mechanism of eutectic structures is the spacing of the secondary phase.

By decreasing the spacing of the eutectic phase, creating a fine eutectic structure, more surface area is shared between the two constituent phases resulting in more effective load transfer.

[16] On the micro-scale, the additional boundary area acts as a barrier to dislocations further strengthening the material.

So, by altering the undercooling, and by extension the cooling rate, the minimal achievable spacing of the secondary phase is controlled.

At lower strains where Nabarro-Herring creep is dominant, the shape and size of the eutectic phase structure plays a significant role in material deformation as it affects the available boundary area for vacancy diffusion to occur.

For instance, in the iron-carbon system, the austenite phase can undergo a eutectoid transformation to produce ferrite and cementite, often in lamellar structures such as pearlite and bainite.

[19] A peritectoid transformation is a type of isothermal reversible reaction that has two solid phases reacting with each other upon cooling of a binary, ternary, ..., n-ary alloy to create a completely different and single solid phase.

[20] The reaction plays a key role in the order and decomposition of quasicrystalline phases in several alloy types.

Because of this, when a peritectic composition solidifies it does not show the lamellar structure that is found with eutectic solidification.

It resembles an inverted eutectic, with the δ phase combining with the liquid to produce pure austenite at 1,495 °C (2,723 °F) and 0.17% carbon.

The alternative of "poor solid solution" can be illustrated by comparing the common precious metal systems Cu-Ag and Cu-Au.

Since Cu-Ag is a true eutectic, any silver with fineness anywhere between 80 and 912 will reach solidus line, and therefore melt at least partly, at exactly 780 °C.

The eutectic alloy with fineness exactly 719 will reach liquidus line, and therefore melt entirely, at that exact temperature without any further rise of temperature till all of the alloy has melted.

In contrast, in Cu-Au system the components are miscible at the melting point in all compositions even in solid.

The composition and temperature of a eutectic can be calculated from enthalpy and entropy of fusion of each components.

[22] The Gibbs free energy G depends on its own differential: Thus, the G/T derivative at constant pressure is calculated by the following equation: The chemical potential