Evangelicalism

[29][30][31][32][33] Christian historian David W. Bebbington writes that, "Although 'evangelical,' with a lower-case initial, is occasionally used to mean 'of the gospel,' the term 'Evangelical' with a capital letter, is applied to any aspect of the movement beginning in the 1730s.

[105][106][107] Other evangelical churches in the United States and Switzerland speak of satisfying sexuality as a gift from God and a component of a Christian marriage harmonious, in messages during worship services or conferences.

[131][132] Healings, academic or professional successes, the birth of a child after several attempts, the end of an addiction, etc., would be tangible examples of God's intervention with the faith and prayer, by the Holy Spirit.

[159] Fundamentalism arose among evangelicals in the 1920s—primarily as an American phenomenon, but with counterparts in Britain and British Empire[157]—to combat modernist or liberal theology in mainline Protestant churches.

Evangelicalism picked up the peculiar characteristics from each strain – warmhearted spirituality from the Pietists (for instance), doctrinal precisionism from the Presbyterians, and individualistic introspection from the Puritans".

[173] Historian Mark Noll adds to this list High Church Anglicanism, which contributed to Evangelicalism a legacy of "rigorous spirituality and innovative organization.

As a protest against "cold orthodoxy" or against an overly formal and rational Christianity, Pietists advocated for an experiential religion that stressed high moral standards both for clergy and for lay people.

The movement included both Christians who remained in the liturgical, state churches as well as separatist groups who rejected the use of baptismal fonts, altars, pulpits, and confessionals.

"[13] After being troubled when his friends asked him to drink alcohol with them at the age of nineteen, Fox spent the night in prayer and soon afterwards he left his home in a four year search for spiritual satisfaction.

"[13] Fox began to spread his message and his emphasis on "the necessity of an inward transformation of heart", as well as the possibility of Christian perfection, drew opposition from English clergy and laity.

[9][13] The Presbyterian heritage not only gave Evangelicalism a commitment to Protestant orthodoxy but also contributed a revival tradition that stretched back to the 1620s in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

There the Half-Way Covenant of 1662 allowed parents who had not testified to a conversion experience to have their children baptized, while reserving Holy Communion for converted church members alone.

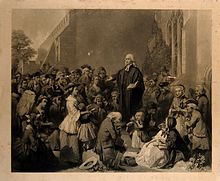

[184] Evangelical revivalism imbued ordinary men and women with a confidence and enthusiasm for sharing the gospel and converting others outside of the control of established churches, a key discontinuity with the Protestantism of the previous era.

[189] One practice clearly copied from European Pietists was the use of small groups divided by age and gender, which met in private homes to conserve and promote the fruits of revival.

Whitefield later remarked, "About this time God was pleased to enlighten my soul and bring me into the knowledge of His free grace, and the necessity of being justified in His sight by faith only.

To the evangelical imperatives of Reformation Protestantism, 18th century American Christians added emphases on divine outpourings of the Holy Spirit and conversions that implanted within new believers an intense love for God.

In Britain in addition to stressing the traditional Wesleyan combination of "Bible, cross, conversion, and activism", the revivalist movement sought a universal appeal, hoping to include rich and poor, urban and rural, and men and women.

[210] Keswickianism taught the doctrine of the second blessing in non-Methodist circles and came to influence evangelicals of the Calvinistic (Reformed) tradition, leading to the establishment of denominations such as the Christian and Missionary Alliance.

According to scholar Mark S. Sweetnam, who takes a cultural studies perspective, dispensationalism can be defined in terms of its Evangelicalism, its insistence on the literal interpretation of Scripture, its recognition of stages in God's dealings with humanity, its expectation of the imminent return of Christ to rapture His saints, and its focus on both apocalypticism and premillennialism.

[220] In 1929 Princeton University, once the bastion of conservative theology, added several modernists to its faculty, resulting in the departure of J. Gresham Machen and a split in the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America.

When [Charles E. Fuller] began his "Old Fashioned Revival Hour" on October 3, 1937, he sought to avoid the contentious issues that had caused fundamentalists to be characterized as narrow.

[229][230] According to William Martin: The New York crusade did not cause the division between the old Fundamentalists and the New Evangelicals; that had been signaled by the nearly simultaneous founding of the NAE and McIntire's American Council of Christian Churches 15 years earlier.

In a letter to Harold Lindsell, Graham said that CT would: plant the evangelical flag in the middle of the road, taking a conservative theological position but a definite liberal approach to social problems.

Spiritual warfare is the latest iteration in a long-standing partnership between religious organization and militarization, two spheres that are rarely considered together, although aggressive forms of prayer have long been used to further the aims of expanding Evangelical influence.

With an emphasis on personal salvation, on God's healing power, and on strict moral codes these groups have developed broad appeal, particularly among the booming urban migrant communities.

[265] Chesnut argues that Pentecostalism has become "one of the principal organizations of the poor", for these churches provide the sort of social network that teach members the skills they need to thrive in a rapidly developing meritocratic society.

Two former Guatemalan heads of state, General Efraín Ríos Montt and Jorge Serrano Elías have been practicing Evangelical Protestants, as is Guatemala's former President, Jimmy Morales.

They are described by the historian Stephen Tomkins as "a network of friends and families in England, with William Wilberforce as its center of gravity, who were powerfully bound together by their shared moral and spiritual values, by their religious mission and social activism, by their love for each other, and by marriage".

By 1848 when an evangelical John Bird Sumner became Archbishop of Canterbury, between a quarter and a third of all Anglican clergy were linked to the movement, which by then had diversified greatly in its goals and they were no longer considered an organized faction.

[306][307] Recurrent themes within American Evangelical discourse include abortion,[308] evolution denial,[309] secularism,[310] and the notion of the United States as a Christian nation.